While the terms “GMO” and “genetic engineering” carry some stigma for certain audiences, to scientists simply agreeing on a definition of what counts as genetically engineered — and what doesn’t — isn’t so straightforward.

“So many things in biological science in particular are a continuum, and drawing a line is kind of arbitrary,” says Richard Amasino, a biochemist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He is also on the committee at the National Academy of Sciences, which produced a recent report on genetic engineering.

“We didn’t focus too much on definition of genetic engineering,” he says, “but we spent a few hours realizing that we just can’t really draw a line anywhere.”

Still, both national and state policymakers have drawn that line. Vermont’s so-called “GMO Labeling” law will go into effect July 1. And it’s triggered a national response. A Senate agriculture committee released a bill this week that would preempt Vermont’s law and instead outlines a different plan for a national, mandatory labeling law.

Despite the common moniker, neither bill uses the term “GMO.”

“Part of the problem is that genetic modification is actually not a scientific term… ‘genetic modification,’ what does that mean? We’ve been modifying plants since way prehistory,” says Jeanne Harris, a plant biologist at the University of Vermont.

But the term "genetic engineering" — which is what Vermont’s law defines — is a bit more specific, says Harris. She describes it as “using tools of modern technology to genetically modify plants.”

"Part of the problem is that genetic modification is actually not a scientific term ... 'genetic modification,' what does that mean? We've been modifying plants since way prehistory." — Jeanne Harris, a plant biologist at UVM

That could include using a gene gun to insert a foreign gene into a plant. Another common method involves using a natural bacterium that cleverly inserts its own DNA into a plant’s — but instead scientists remove the bacteria’s DNA and replace it with the DNA they intend to add into the plant.

These techniques are considered genetic engineering in Vermont’s law.

Evolving a modern food crop

But there are other methods of adding, deleting and duplicating a plant’s DNA that are not considered genetic engineering under the legal definition. For example, a process called mutagenesis.

“So we can use chemicals mutagens, or UV or something like that, that will actually make nucleotide changes within genes, and maybe disrupt their function or change their function,” says Jill Preston, a plant biologist at the University of Vermont.

To be clear, this technique doesn’t involve inserting new or foreign genes into the plant, it’s more like “what evolution does; we have mutations happening all the time. This is just more directed by humans.”

To make these changes, scientists either blast a plant’s DNA with radiation or use a chemical that disrupts the DNA.

It’s not unlike when sunlight radiates DNA and causes mutations; scientists are just speeding up the process.

But just like evolution, it’s random. So there’s no way for scientists to know what kinds of genetic changes will result.

Speeding up Mother Nature

Harris says she wouldn’t consider it riskier than modifying one particular gene, “it’s just totally untargeted.”

Harris says for example say scientists were trying to create a lettuce plant that didn’t bolt— so they’re looking to make a genetic change that would delay flowering in lettuce.

“If you mutagenize it, you have no idea, so you’d have to look through 10,000 little lettuce plants to find the one that you wanted. If you’re doing genetic engineering, you could say, ‘OK, we know these four genes are involved in the timing of flowering, let’s try targeting those’—it’s more directed.”

Harris says mutagenesis could ultimately produce a plant with delayed flowering, “but you don’t know what other [genes] have also been hit — it’s impossible to mutagenize and only hit a single gene.”

Mutagenesis has been used in various forms for decades. In fact foods that we eat today, like some kinds of rice, oats, lettuce and Ruby Red grapefruits come from seeds created through this process.

Canada considers plants produced with mutagenesis to be genetically modified and regulates. European authorities will not allow them to be labeled organic.

And Harris says from a science perspective, she thinks it makes sense not to consider this technique genetic engineering, since it’s mimicking nature’s process.

Canada and the European Union, on the other hand, do make a distinction.

Canada considers plants produced with mutagenesis to be genetically modified and regulates. European authorities will not allow them to be labeled organic.

It’s the destination, not the journey

But scientists interviewed for this story say we shouldn’t focus so much on how the crop was created, but instead look at the end product.

“One could, in a laboratory, change a couple nucleotides in a gene, and one could also accomplish that through mutagenesis — and the products would be identical,” says Amasino.

“Yet, at least by regulatory definitions that presently exist, one would be genetic engineering and one would not be.”

Amasino and other scientists say the real scientific issue, with respect to human health, or safety of ecosystems is revealed by studying the product, not the route by which we got there.

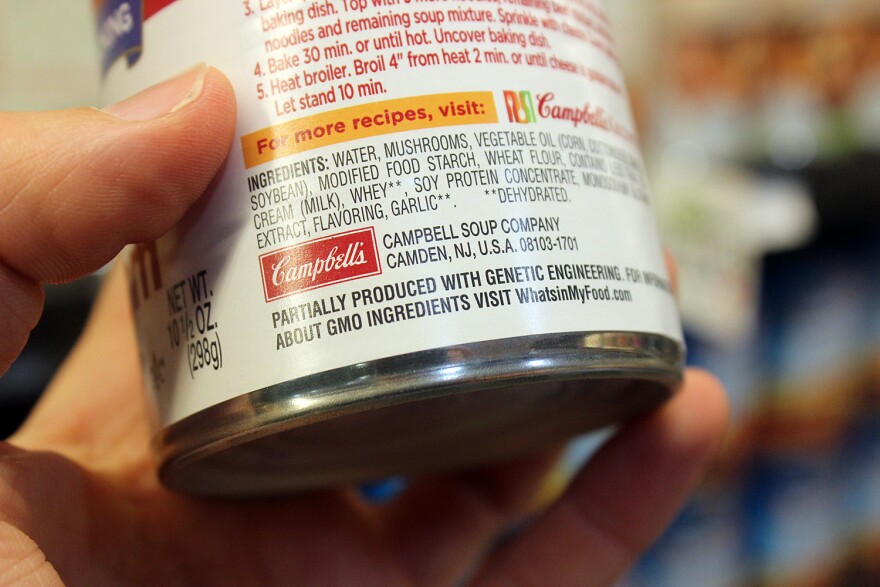

In the meantime, processed foods are already arriving on grocery shelves with genetic engineering label, which may tell consumers a bit more than they knew before about how their food was made.

This report comes from the New England News Collaborative. Eight public media companies coming together to tell the story of a changing region, with support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.