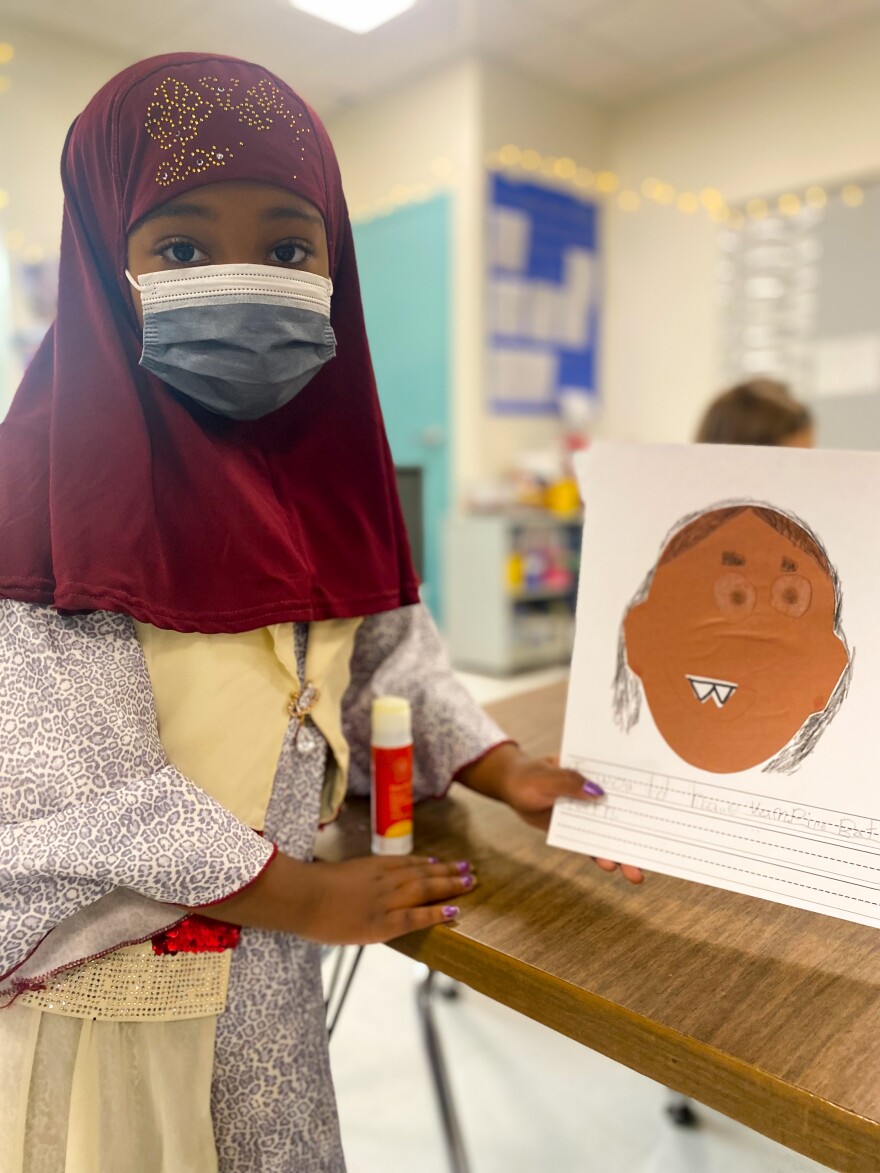

In a first grade classroom at Burlington’s Champlain Elementary, Janelle Gendimenico guides her students through a lesson focusing on the importance of getting every word in a sentence, especially when you’re talking about animal teeth.

"Show me with your fingers. What does the naked mole-rat’s teeth do?" Gendimenico asked the class. "They go back left and right, left and right."

Gendimenico is an English language learning specialist. She co-teaches the class with Taylor Warner, a mainstream first grade teacher. The students are an even mix of English learners — meaning they speak a language other than English at home — and native English speakers.

Some urban school districts in New England teach children from dozens of countries across the globe. The variety of languages they speak is something teachers are increasingly treating as an asset, rather than something the kids need to overcome.

There are over 40 languages represented among Burlington students and their families; nearly one in five kids is an English learner. At home they speak Nepali, Somali, Maay Maay, Bosnian, Swahili and other languages.

One goal of this combined, co-taught class is to make sure the English learners are fully integrated into every part of school. That’s an improvement on the much more common practice of pulling English learners out for special instruction, Gendimenico says.

"That distinguishes them from the rest of the class," she said. "They're the students that have to leave; they're the students that have to go to get what they need for 30 minutes. And then the rest of the time the classroom teacher has to do it on their own."

Co-teaching is one aspect of the Burlington School District’s recent efforts to support English learners by embracing their multilingualism.

Miriam Ehtesham-Cating, who directs the district's programs for multilingual learners, says English learners are often given school work that’s too easy for them.

"What I'm trying to not do: number one, to underchallenge English learners — anywhere, ever, for any reason," she said.

Nepali students make up the largest portion of English learners in Burlington, and middle school can be a time when many of them lose interest in school and sort of drop off the map, according to Ehtesham-Cating.

In Burlington, not only are educators pulling fewer English learners out of classes, they’re adding resources to help students make use of the many strengths that come with being multilingual.

"It's specifically not about erasure, but about kind of an additive way of thinking about language and culture," Ehtesham-Cating said.

One of the district’s newest initiatives is to hire Nepali-speaking language support specialists.

Sunita Basnet works with kids in and out of the classroom, including a group of a dozen or so students in the library of Burlington’s Hunt Middle School a couple times a week.

In the classroom her job is often to help individual students with English. Here, however, she’s helping them with their Nepali.

"What we are focusing [on] is when they speak our own language here, they learn more," Basnet said.

Research has shown that a student’s command of their home language has a direct impact on their success learning English in school, but second- and third-generation immigrants can sometimes get stuck lacking fluency in English and in their home language.

Basnet’s Nepali affinity group is designed to counteract that trend. And she says there’s an even more pressing reason for her students to practice their Nepali — so they can talk to their grandparents.

"At least if they say like, 'namaste' — 'hi, hello' — that would be enough for some grandparents and parents. So that's why I just want to encourage them. We need our culture. We have to keep our culture," Basnet said.

It’s also about showing multilingual students that school is a place to bring their full selves, but convincing a middle schooler of that is no easy task.

Basnet and Ehtesham-Cating told a story of one student who didn’t want to engage with Basnet in English or Nepali. In one class he threw his work in a waste basket while Basnet watched.

"What he did was, he just screwed all his papers and then he just made it a ball like that and then threw in the trash," Basnet said.

"She waited a couple of minutes — you know, let it go. And then she went over to the garbage, got the paper out, smoothed it back out. And she was being cool," Ehtesham-Cating said.

"And after some time, the teacher came and said 'Where's your notes?'" Basnet said.

"She gradually brought it over and just pushed it towards him on the table and said 'Do you want to finish this?'" Ehtesham-Cating said.

The boy nodded eagerly, Basnet says. He took the work back, finished it up and handed it in. Now he talks to Basnet every day in English and Nepali.

"And then I thank God, like 'Oh, God, thank you for this boy.' And then that's why I'm here," Basnet said.

Despite requests, neither the Burlington School District nor the Vermont Agency of Education provided data on graduation rates for English learners. That makes it difficult to assess the impact of their new multilingual initiatives.

But thanks to Basnet, at least one student got his work in on time.

Have questions, comments or tips? Send us a message or tweet us @vprnet.