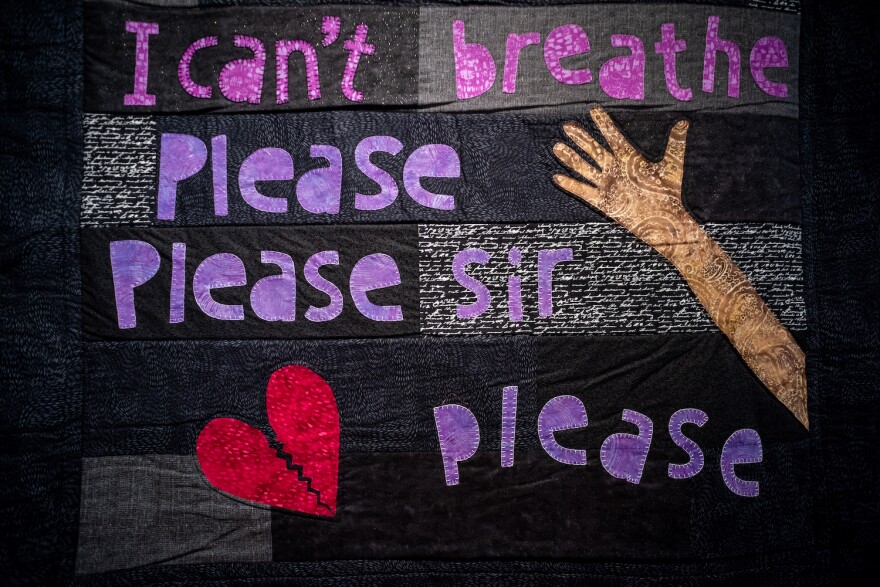

"Stitch, Breathe, Speak," a film by Chris Owen, follows a group of churchgoers from nine New Hampshire parishes and what they did in the wake of George Floyd's murder. It features quilts sewn by parishoners, using the last words spoken by George Floyd before he was murdered by a Minnesota police officer in 2020. The film touches on what the quilt panels and Floyd's words brought to the ones making them.

The film is the latest in our Made Here series, now in its 18th season. It's available to watch on our website, and the documentary is airing on our main TV channel at 8 p.m., tonight.

Rev. Mark Koyama leads The United Church of Jaffrey in New Hampshire. In the film, we see Koyama, who knows his mostly white congregation wants to be allies in the racial justice movement, coming up with the idea to stitch Floyd's final words on quilt panels. Koyama wanted to create opportunities for his congregation and the wider public to see the words and begin to have conversations about racial injustice.

Koyama said the idea to make a quilt grew from other sewing projects like the AIDS quilt.

"There is a precedent for quilting being a narrative mode of activism and also expression." - Rev. Mark Koyama, on the George Floyd quilting project that turned into a church ministry

Dr. Harriet Ward, the chair of the anti-racism ministry group for the New Hampshire Conference of the United Church of Christ, plays a pivotal role in the creation of these quilt panels. Ward is the only African American member of her church congregation as well as the only quilter.

Both Ward and Koyama recently spoke to Vermont Public's Mary Williams Engisch about the film that documented what began as multiple quilt panels and turned into a ministry. Their conversation below has been condensed and edited for time.

Mary Williams Engisch: Well, I'll start off with you, Mark. In the documentary, you approached your congregation with this idea of making a quilt because you knew that parishioners wanted to express their emotions, their feelings about George Floyd's killing. How did you come up with this particular idea?

Mark Koyama: It was quite organic, in the sense that it grew from a request that I got from a parishioner. She asked me if I could help her to gather together fabric so that she could put together a Black Lives Matter banner, it kind of set off a chain reaction of ideas for me. There was the AIDS quilt, right? So there's a precedent for quilting being a

mode, a narrative mode of, of activism, and also expression.

I received a email from a group that was promoting police reform, because of course, this was a week after George Floyd was killed. And in the body of that email, they included the final words that George Floyd had spoken as he was pinned to the sidewalk.

And then I realized part of the way through the reading list that I was reading the words of a man who is pleading for his life.

These are words that you can't look away from. We then sent a proposal out to all the churches in New Hampshire, nine churches respond. So that's how it began.

And Harriet, I'll ask you to while we were getting ready for this conversation, you shared that you're the only African American quilter on this particular project. What were your thoughts? On the initial idea? Did you think that this was something that you wanted to be involved in?

Dr. Harriet Ward: Well, first, I thought of it as a quilter. And I wondered, how on earth are you going to get a whole bunch of quilters who don't know each other during COVID, to come up with anything that made any sense? And I have to say, when Mark talked about looking at this, almost like a piece of poetry, it almost reads like a psalm in its own sad way. When I read it, I saw that.

And I had misgivings as a quilter. I was the only African American in my church. And I knew something. And in the beginning of my work with this, I realized that European quilters - people descended from Europeans - were not going to feel this or see this or, or experience this in the same way I was.

There was an experience from perhaps having witnessed something but not having experienced it. They can witness the inequity. They can witness the things that happened to African Americans, but they can't experience them.

Well, I can experience them. And so in discussion about what to do. I'm talking to people who are kind of clueless about what this really means to someone who looks like me. If you're white, looking at this is completely different than my experience.

And Mark, you will also openly grapple with whether this quilt, using George Floyd's last words is exploitative. What were you thinking there? And why did you ultimately decide that it wasn't, and that this could be something that now it has turned into a ministry?

Rev. Mark Koyama: I raised that question fairly early in the film. Is this an exploitation of the words of a dying man? But that question is never really fully answered by the documentary itself.

And so in some ways, we've kind of embraced that ambiguity as a way of of furthering the discussion about the subject matter that is oftentimes a subject that many people would very much prefer not to have.

I call it a rhetorical sleight of hand. In a sense, what they [the quilts] do is they invite you in as a kind of comforting idea, because that's what quilts are, they're comforting. And they're an expression of love. And then once you're invited in, the quilts have this remarkable ability to kind of open conversation that otherwise people really prefer not to have.

One of the amazing things that Harriet contributed to our process, when we were making the quilts was she helped us to remember that this was not a current event.

And in the film, you say that you're basically imploring people to not go through outrage and amnesia. But Harriet, what do you mean, when you say, "Do not let this continue to be outrage, and then amnesia?"

Dr. Harriet Ward: It is the news cycle. Your outrage follows the news cycle. And when it's not news anymore, you go back to whatever you were doing.

But when it's not news to you anymore, it's still with me. And so these words are just endless in the life of many Black people.

I have to say that I've made my mind up. It's not exploitation, thinking back on what Mark said. It's an expression of love. It's an expression of love.

And there's no way in my mind that this question of love isn't exploitation. And I'm a Black person. And I did this and I did not for one minute feel that there was any exploitation.

I was feeling like there was an opportunity to get people to open their hearts and minds to this discussion that nobody wants to have, that I want to have. So this is personal. Personally, personally, it's not an exploitation. It's a needed conversation. And something's been created with that conversation to happen. Something nobody ever wants to talk about. Well, I want to talk about it.

Reverend Mark Koyama from the United Church of Jaffrey in New Hampshire and Dr. Harriet Ward, is chair of the anti-racism ministry group for the New Hampshire Conference of the United Church of Christ. Since the creation of the nine quilt panels with George Floyd's last words, Ward and Koyama created the Sacred Ally Quilt Ministry.