If you're finding it harder to remember where you put the car keys, the culprit could be a brain protein with a name that's easy to forget: RbAp48.

A shortage of this protein appears to impair our ability to remember things as we age, researchers report in the current issue of Science Translational Medicine. And boosting levels of RbAP48 in aging brains can reverse memory loss, at least in mice, they say.

The protein was studied in an area of the brain that is generally unaffected by Alzheimer's disease. The research "reinforces the emerging idea that Alzheimer's disease and aging are separate entities," says Scott Small, a neurologist at Columbia University and one of the study's authors. It also suggests that, eventually, it should be possible to treat memory loss that's not related to Alzheimer's.

Small and a team that included Nobel Laureate Eric Kandel discovered the protein after studying postmortem brains from eight people ranging in age from 33 to 88. The scientists focused on one specific region of the hippocampus, a structure that's highly involved in memory.

"We simply asked: Can we find a molecular change in that brain region across the lifespan?" Small says. The answer was yes. In the brains of young people, the RbAp48 protein was abundant, the researchers report. But in older people it was scarce.

The team still needed to show that this protein really is responsible for memory loss. So they found a way to artificially reduce levels in young mice, Small says.

"What was remarkable is that if you just manipulate this one molecule in this particular area of the brain, you now have a young mouse that looks very much like an old mouse," Small says. These young mice had trouble remembering new objects and things like how to get through a maze.

Then the researchers tried something even more ambitious. They boosted levels of RbAp48 in old mice with failing memories. The effect was dramatic, Small says. "Their ability to detect novel objects went back to the way a young mouse is able to perform that task," he says.

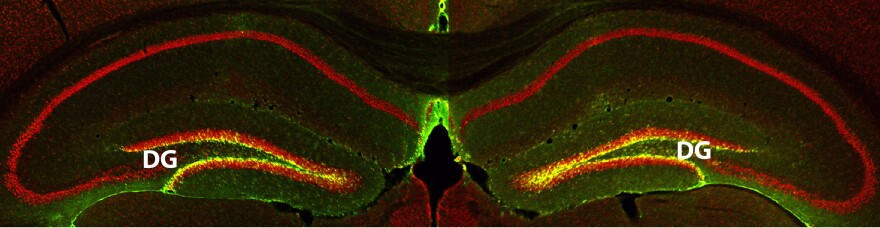

All of these experiments involved what's called the dentate gyrus — a region of the hippocampus that is generally not affected by Alzheimer's disease. Also, the RbAp48 protein hasn't been linked to Alzheimer's, Small says.

The findings could eventually help doctors determine whether someone's memory loss is a symptom of early Alzheimer's or just normal aging, Small says. "That's become the most common question I get" from patients, he says.

The new study is both beautiful and important, says David Sweatt a neurobiologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine. The findings suggest that a drug could reverse memory loss in some people with age-related memory loss, Sweatt says.

But the possibility of finding such a drug raises a tricky question for society. "If it's normal, do you need a drug for it?" Sweatt says.

Sweatt thinks there is a need because even normal memory loss impairs the lives of many people in their 70s, 80s and beyond. But a drug isn't the only option for increasing levels of this memory molecule, he says. Other likely candidates include diet and exercise, which scientists already know can affect the levels of some proteins in the brain.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDIxMDkyNjUxMDE0NDY1Njg1NzRiOTRiYQ000))