Vermont author Kekla Magoon continues to garner awards for her young adult books.

Her latest is a work of nonfiction chronicling the history of the Black Panther Party, called Revolution in Our Time: The Black Panther Party’s Promise to the People, and it’s been named a Walter Award Honor Book in the Teen category for 2022. It’s also won the Michael L. Printz and Coretta Scott King author awards, not to mention being a 2021 National Book Award finalist.

VPR’s Mitch Wertlieb spoke with Magoon about the book. Their conversation is below and has been edited for clarity.

Mitch Wertlieb: Why did you want to write a book about the Black Panther Party for younger readers?

Kekla Magoon: There were a couple of reasons that all came together at once. I grew up in Indiana in a predominantly white community. And even though I was very passionate about history, and especially Black history, and especially the civil rights movement, I never learned very much at all about the Black Panther Party even as a young black woman.

And so it wasn't until after I graduated from college and moved to New York City, and was working as a grant writer, that I stumbled upon an article about the Black Panther Party’s free breakfast program for schoolchildren. And that just totally opened my mind to all the different work that the Panthers had done.

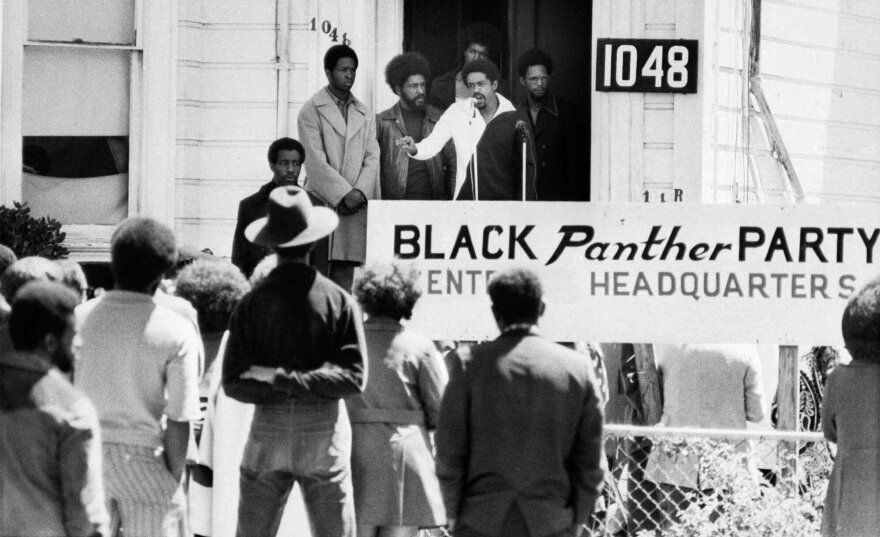

The image I had always had in my mind was Black men with guns bad, scary — so bad and so scary, in fact, that we don't talk about it, we don't teach it in history class. And so when I learned that the Panthers were community organizers, and they had health clinics and breakfast programs and grocery programs and senior escort programs and legal aid, I especially wanted to share that history with young people, who deserve the opportunity to know this history.

Bobby Seale and Huey Newton probably the best known names associated with the movement. Are there other names that are lesser-known that you bring to light in this book?

Absolutely. In fact, my goal was not to tell a single biography of a single Panther, but to tell a biography of the party as a whole. The party was founded in Oakland in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. But there were so many chapters — in more than 40 cities, the Panthers were active.

The people who really did the work were people who many of whose names we will never know. Women in particular, who are the majority of the party. So you have people like Kathleen Cleaver, who is still an educator, speaker, very powerful leader who was the communications secretary for the party. Elaine Brown, who continues to advocate and educate around the country as well. She was the chairwoman of the party for a period of time after Huey Newton was forced to step down. Ericka Huggins was a political prisoner in the late 60s, early 70s, and was the leader of the New Haven chapter of the Black Panther Party, is still an educator today.

There were so, so many people that were part of this movement that really changed the landscape of organizing in this country.

"The image I had always had in my mind was Black men with guns bad, scary — so bad and so scary, in fact, that we don't talk about it, we don't teach it in history class. And so when I learned that the Panthers were community organizers, and they had health clinics and breakfast programs and grocery programs and senior escort programs and legal aid, I especially wanted to share that history with young people, who deserve the opportunity to know this history."Kekla Magoon

The Panthers did not preach nonviolent resistance in the fight for civil rights as Martin Luther King, Jr. did. How do you handle the question of violence that's associated with the Black Panthers in this book?

So, the civil rights movement that we talked about as a nonviolent civil rights movement was actually a movement steeped in violence. The violence was not coming from the protesters, the violence was coming from the police, was coming from white supremacists, was coming from counter-protesters as people engaged in civil disobedience and marched for justice.

There's a famous march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Alabama, where John Lewis, the late congressman, was beaten by police. They were trying to make a peaceful march from Selma to Montgomery, and were beaten.

He almost died.

Yeah, absolutely. You know, there are many examples of people who almost died. There are many examples of people who did die in the fight for justice. And it's important to realize that the power of nonviolent resistance was that it was nonviolence in the face of extreme violence at the hands of people who often had greater power in society.

When Dr. King was killed in 1968, the few years before that, there were uprisings in communities all around the country. We had the Watts uprising in Los Angeles after an incident of police brutality. There were similar protests in Detroit, in Newark, New Jersey, in Harlem, New York, there were communities of young Black people rising up in anger and protests and lashing out at this pervasive systemic racism and violence that was happening to Black communities.

And so in the face of that, what the Panthers did was, they said, "OK, we do need to defend ourselves against the violence that's happening to us." So it was never a question of advocating violence. It was a question of preventing violence. The Panthers' first program was called "Policing The Police." They followed police officers, they carried weapons that were legal in California at that time, and followed the police officers to watch them doing their work, on the logic that police brutality happens when no one's looking.

What if people were looking, and what if those people who were watching said, "Hey, you do your job legally with respect for who we are. Nobody's gonna have a problem. But you start stuffing, bottom line, we're here to defend our community"?

And it meant taking care of people in other ways, which is why they did so much organizing around employment justice, work with unions around fair wages. They boycotted businesses in the community that were very exploitative. They did a lot of work around housing justice, organizing for tenants’ rights. All of those activities were part of what they considered self-defense of the community.

And some of those economic strategies you're talking about were very much embraced by Dr. King before he died.

Absolutely.

I want to bring this up to the present time, because there's been a lot of news lately about books, either being labeled problematic or calls for outright bans on some young adult books.

I've spoken about this with another Vermont young adult author, I think that you know well, Jo Knowles. And, you know, she had two of her books flagged in a school district in Texas for what some parents said, was pornographic material. In reality, there wasn't anything remotely like that in the books, but both of them did feature characters who are gay, which is what Knowles felt the opponents really were objecting to.

Have any of your books, maybe even this one, faced similar opposition that you know about? Are you concerned at all if they do that, perhaps an audience that could benefit from reading about the Black Panthers and the real story of them, won't get a chance to do so if your books are labeled in this way?

I think certainly in this landscape, there's the risk of that. This particular book is new, it came out in November, it hasn't, to my knowledge, appeared on any of the banned book lists, but some of my previous books have regardless of their content.

Most of my books do have Black characters, Black or biracial characters. So one of my middle-grade novels, ended up on one of the banned book lists from one of the school districts in, I believe in Pennsylvania, and then also on the one of the lists from Texas. And you know, that's a novel that's not about civil rights. It's not about social justice. It's about three Black boys in Indiana having a summer adventure.

So it was never really about the content. It was about the idea that we tell stories about Black characters. It's already been a struggle for the last 50 or 60 years and beyond, to actually get a history of marginalized communities taught in school.

When the Black Panthers were active in the late 60s and early 70s, there wasn't a Black History Month, or Black Studies curriculum available at universities or high schools, you know, around the country. And so the Panthers were actually instrumental in getting that history taught. And so it's very much a part of their legacy to bring education, about the truth of who we are and what our history is to people, so they can use that information to empower themselves to change the world in continually better ways.

Have questions, comments, or concerns? Send us a message or tweet your thoughts to @mwertlieb.