Rich Holschuh isn’t sure yet what he’ll be doing on the second Monday in October later this year. But he says the celebration of Vermont’s first Indigenous Peoples' Day will no doubt be a big one.

“This seems like a small thing, you know? It’s just a day, a holiday - what’s the big deal?” Holschuh said recently. “But it’s big. It’s a big idea.”

Last week, Gov. Phil Scott signed legislation that eliminates Columbus Day from the list of official state holidays, and replaces it with a new holiday, called Indigenous Peoples' Day.

The bill signing capped three years of work by Holschuh and other advocates, who say the annual commemoration of Christopher Columbus has in many ways obfuscated the role of indigenous people in the founding of the United States.

“I think what it’s going to help achieve is a restoration of the Abenaki and the other indigenous people to a more complete level as human beings,” Holschuh said.

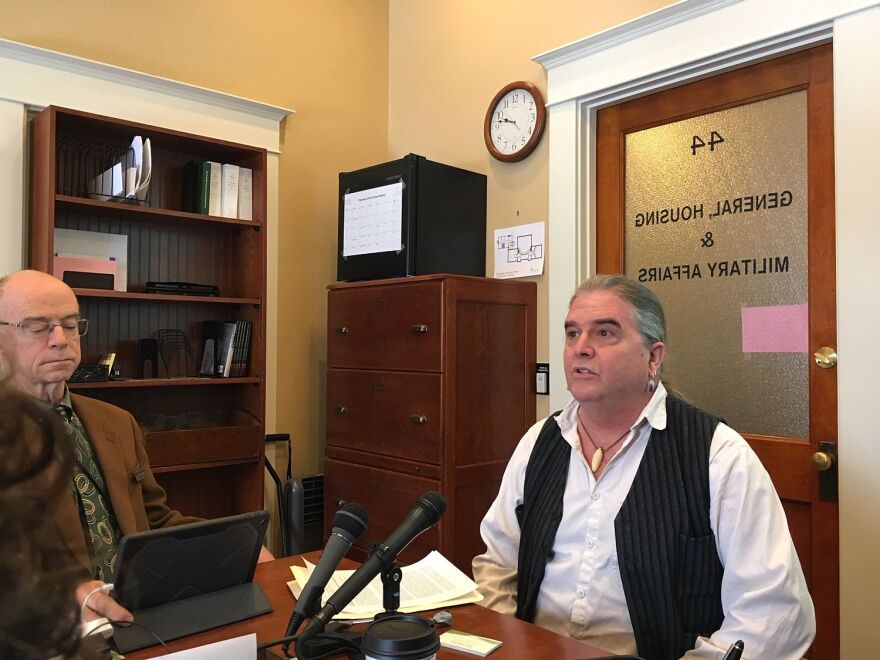

Holschuh, a member of the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs, greeted lawmakers in Abenaki earlier this year when he testified in favor of the Indigenous Peoples' Day legislation.

It isn’t often that lawmakers hear indigenous languages in the Statehouse. And Holschuh said the people that once spoke them have in many ways been relegated to a historical footnote in stories of the nation’s founding.

“Columbus is very much a part of these stories,” Holschuh told lawmakers. “But we now know that he was not the idealistic magnanimous, inspirational figure that we were … taught.”

Testimony from Holschuh and other advocates resonated with lawmakers in the House and Senate, both which passed the legislation by an overwhelming margin. When Scott signed the bill into law last week, Vermont became the third state in the country to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day. New Mexico and Maine enacted similar laws earlier tihs year.

Not everyone was ready to dispatch with a holiday that has special resonance for many Italian Americans. Karl Miller is the secretary of the Barre Mutuo, an organization that pays homage to the city’s Italian heritage.

“I am all for an Indigenous Peoples’ Day, absolutely,” Miler said in March. “But the casting aside Columbus Day I think is a tragedy, I really do, for the American people in general.”

Miller didn’t contest the fact that Columbus did some bad things - his role in the enslavement of native people, for instance, is well documented.

But Miller said the day isn’t about honoring Columbus as a hero so much as it is about recognizing the contributions of the Italian communities that later settled here.

“Lord knows where we would be here today, what it would be like here in America, if there even would be a so-called America,” Miller said.

For Beverly Little Thunder, however, a Huntington resident, and an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Lakota Band, in North Dakota, the holiday is symptomatic of a Euro-centrism that has been ingrained in American culture and history.

“It’s always been an affront to me that we would celebrate someone who had committed such atrocities as Columbus did,” Little Thunder said.

For the past three years, Govs. Peter Shumlin and Scott have issued proclamations recognizing Columbus Day as Indigenous Peoples’ Day. But Little Thunder and Holschuh said it’s time for a more permanent and legally binding declaration by the Legislature.

“And so by having an Indigenous Peoples’ Day, perhaps the whole truth would come out, perhaps the whole history could be taught,” Little Thunder said.

UPDATE: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Vermont was the first state to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples' Day.