Getting back into a packed sports stadium to watch their favorite team compete is likely near the top of the list of what sports fans are looking forward to once the coronavirus pandemic ends. Vermont author Larry Olmsted argues in his new book that sports fandom thrills and entertains as much as it fosters our mental health and sense of belonging. VPR’s Mitch Wertlieb spoke with author Larry Olmsted about his latest book Fans: How Watching Sports Makes Us Happier, Healthier And More Understanding. Their conservation below has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Mitch Wertlieb: Full disclosure, you're preaching to the choir here. I love sports — playing, watching, but make the case for somebody like, let's say, my sister, who could not understand even remotely why I was so upset when the Red Sox traded one of their best players ever in Mookie Betts to the L.A. Dodgers a couple of seasons ago. She had no idea who Mookie is, or why I care about a bunch of players who don't really have a connection to my actual life.

How can watching professional sports make a person happier and more understanding?

Larry Olmsted: Well, there's been tons of psychological studies and there's ample evidence that sports fans are happier and enjoy elevated benefits in several different mental health areas than non-fans. But I think what would interest your sister is all the ways in which sports fandom affects society, even if you're not a sports fan. It makes the world a better place to live in. Things like the Civil Rights movement, and the social justice movement, and post-traumatic healing of society — these are all areas I get into that make the world better for all of us, even your sister.

Does it make a difference whether you're watching sports in a stadium, or if you're just watching it at home on television?

It does, but it doesn't make as much of a difference as you might think when it's not a pandemic. A lot of the mental health benefits we enjoy from sports, [like] lower rates of depression, higher self-esteem, all stem from this sense of community we get [from sports]. Which is why it's called Red Sox nation. Sports fans, when they're interviewed, even when they're alone on the couch, say that they feel like part of the crowd.

Now, I'm a Star Wars fan, but I watch a movie on TV, the audience has no role in it. I don't feel like I'm with anybody else. And with sports, it's amplified because you also see the Red Sox bumper sticker [on someone else’s car], and you go to the supermarket and you have your Red Sox hat on and you pass somebody with a shirt, and you make eye contact and you're connected with strangers all the time, whether you're watching the game or not.

But isn't picking a sports team, in the sense people identify with Red Sox nation or what have you, just another form of tribalism? I mean, you could make the argument that we have enough of that kind of “us versus them” mentality already in this country.

You could make that argument. And probably the biggest negative that I found throughout my research was this [idea that] “I hate the Yankees because I like the Red Sox, and I hate their fans, even though I don't know them.”

But, you know, there's two elements to that. One is: we’re tribal creatures. That's why we crave the sense of community and belonging, and humans since the Stone Ages have formed tribes and communities.

But the good news is — and I have a chapter in my book on fantasy sports, which is a relatively new phenomena at the scale it is [at] now, with nearly 60 million people in North America participating — now you have to have somebody from the Yankees or, you know, your [any other] hated team, if you want to win. It's sort of transforming people who play fantasy sports into less hard-edged fans of their own teams, and more fans of the sport.

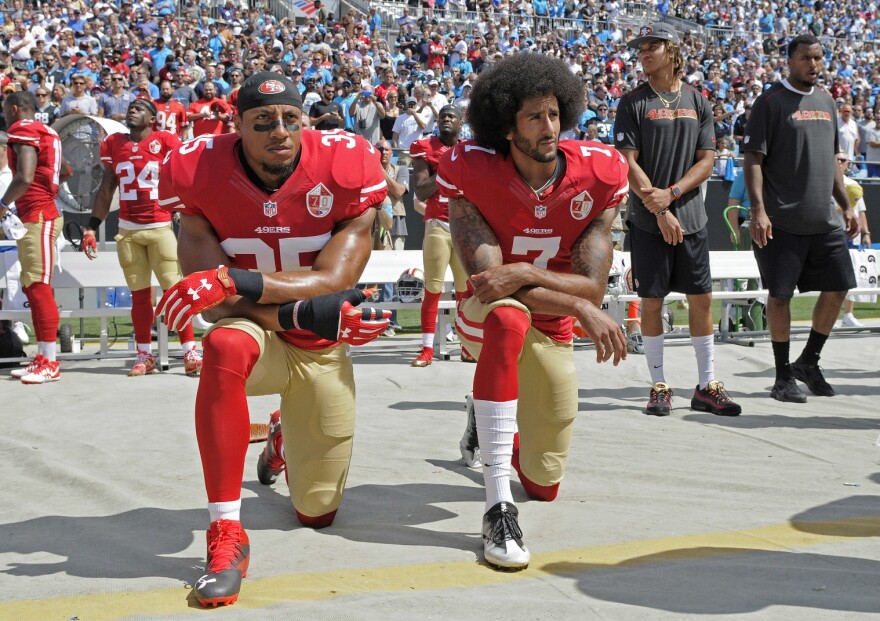

I want to get back to what you were saying about how sports often overlap with history — [take] the 1936 Olympics, where Jesse Owens shut down Hitler and his racism by doing so well. But when things get political — think of Colin Kaepernick, for example, kneeling at the national anthem, and the outrage that garnered from so many people — a lot of those fans say sports in years gone by were free from that kind of protest; nevermind that Jackie Robinson also refused to stand for the national anthem.

And there are many other examples of sports and politics overlapping. Can people of different political views still come together by watching sports?

Absolutely. I call it in the book 'The Universal Language', because I've traveled a lot around the world, to every inhabited continent, and I could go into any airport bar anywhere in the world and sit down, and there's going to be something on the TV over the bar — could be cricket, could be anything — and I could turn to the person next to me and acknowledge the game, and I have a new friend.

Let's say you go into an airport and you're sitting down, watching a football game and, you start bonding with that stranger you've never met before. Because, you know, you both love the Patriots, for example. Then let's say that person says to you, “You know, it really annoyed me when Kaepernick kneeled during the national anthem.”

Let's say you agree with what Kaepernick did. Can you still forge that bond with that stranger, even though you now know you have very different political views?

Yes. And I would disagree with them, but sports are unique, in the sense that a lot of fans have always felt that they should be separated from politics.

But there have always been activist athletes, and sports have [long] been used for political purposes, even by our government. You know, the president invited Joe Louis to the White House before his fight and said, you know, "Your muscles have to fight Nazi Germany."

What has really changed is the advent of social media. So when John Carlos and Tommie Smith at the [1986] Mexico City Olympics raised their fists, they had to rely on newspaper pictures, and someone to get their message to the people. But LeBron James can to tweet tens of millions of people directly. And that, in turn, has forced the teams and the leagues to take a stand, which they never did before.

This is all an extension of something that has been going on since Jackie Robinson.

I remember this Jerry Seinfeld routine where he said, because players change teams so often now—there’s trades, there's free agency, nobody sticks around very much anymore, in any sport—that you're really just rooting for laundry, the jersey on the back of the player. Does that matter? Is he right?

He is right. And he hits on a very vital point. The only thing that I found in the world on a scale comparable to sports in terms of its role in the fabric of our lives would be religion. [The] main two drivers of what religion you belong to are where you're born and what your parents practice. And it's exactly the same with sports.

You know, you don't wait until you're like 15 and say, "Hey, I want to be a Red Sox fan." You're sort of a Red Sox fan because you were born in New England, and your parents maybe watched the game. It’s a little different for college, which is driven by where you went. So, you're not really rooting for the laundry, you're rooting for the team.

And it's also what really differentiates team sports from independent sports. You know, you might be a big Tiger Woods fan, but Tiger Woods is going to stop playing at some point. He may have already. But the Red Sox will presumably be playing 100 hundred years from now.

Have questions, comments or tips? Send us a message or tweet Morning Edition host Mitch Wertlieb @mwertlieb.

We've closed our comments. Read about ways to get in touch here.