Almost everywhere in the U.S., including western Massachusetts, a shortage of public school educators is putting a burden on staff and students.

"The problem is there are not enough people in general going into education," said Bob Bardwell, executive director of the Massachusetts School Counselor Association (MASCA).

The pandemic created a shortage of teachers, but Bardwell's concern is a shortage of school counselors.

Colin Moge, a West Springfield High School counselor, said his own counselor essentially made sure he graduated from high school — which was in question — but the job has changed considerably.

"I think what really has changed in the past five to 10 years is [the job] doesn’t just include academic counseling," said Moge. "It also includes supporting students interested in trade schools or entering the work force and two- [or] four-year colleges."

A significant "social-emotional" component of the work is the biggest change, Moge said. That's essentially helping students navigate their daily lives, in and out of the school community.

That guidance, though, is not just for high school students. Elementary school counselors are also wrangling with these matters.

"[An elementary school counselor] might do a series of lessons in a third grade classroom that talks about options after high school, let alone, 'How do I get along with others? How do I not hurt someone's feelings? How do I be empathetic?'" said Bardwell, a longtime educator in western Massachusetts who now oversees more than 100 school counselors in Boston's public schools.

At every grade level, since the pandemic, chronic student absenteeism is a significant challenge.

Add to that, in high school, counselors are still helping students manage epic college financial aid delays caused by the U.S. Department of Education's revamp of its FAFSA forms. That's been especially hard on students who thought college was already unattainable because of the high costs, Bardwell said.

These are just the latest issues to surface as a shortage of qualified counselors potentially worsens.

"As more people retire or more people quit, or the profession is burning people out, you're not going to have enough people to replace those that are leaving," Bardwell said.

Not every job goes unfilled, but some districts are hiring people with temporary state licenses. Some other districts are eliminating school counselor jobs altogether or leaving them unfilled, as school budgets are alarmingly tight with an increase in a variety of expenses, including transportation.

MASCA is addressing the shortage, Bardwell said, first by trying to understand it.

Jennifer McGuire and Dana Catarius, both longtime school counselors, are on the MASCA board and among the educators creating a multi-year plan, attempting to increase the number of school counselors in the state. First, they are surveying undergraduate students.

"Why are people not entering the field or why are they entering the field and not staying?" McGuire said the survey aims to find out.

Then they want to make sure college students and even high schoolers see that becoming a school counselor is an option.

"People who are coming up in teaching, people who are psychology majors," Catarius said.

MASCA is also in the process of producing a video, trying to capture the broad scope of what school counselors do in a variety of districts.

The overall goal, in concert with the Massachusetts Department of Secondary and Elementary Education (DESE) and other education groups, is to increase the number of people who start and finish graduate programs and specifically pursue school counselor jobs.

Massachusetts school counselors are overwhelmingly white, including in most districts with a majority of students of color, like Holyoke and Springfield.

That's slowly changing, but DESE and others say they are trying to build a more racially and culturally diverse educator workforce, as the student population continues to diversify.

It's not just large districts experiencing the counselor shortage. The short-staffing is also hitting rural school districts.

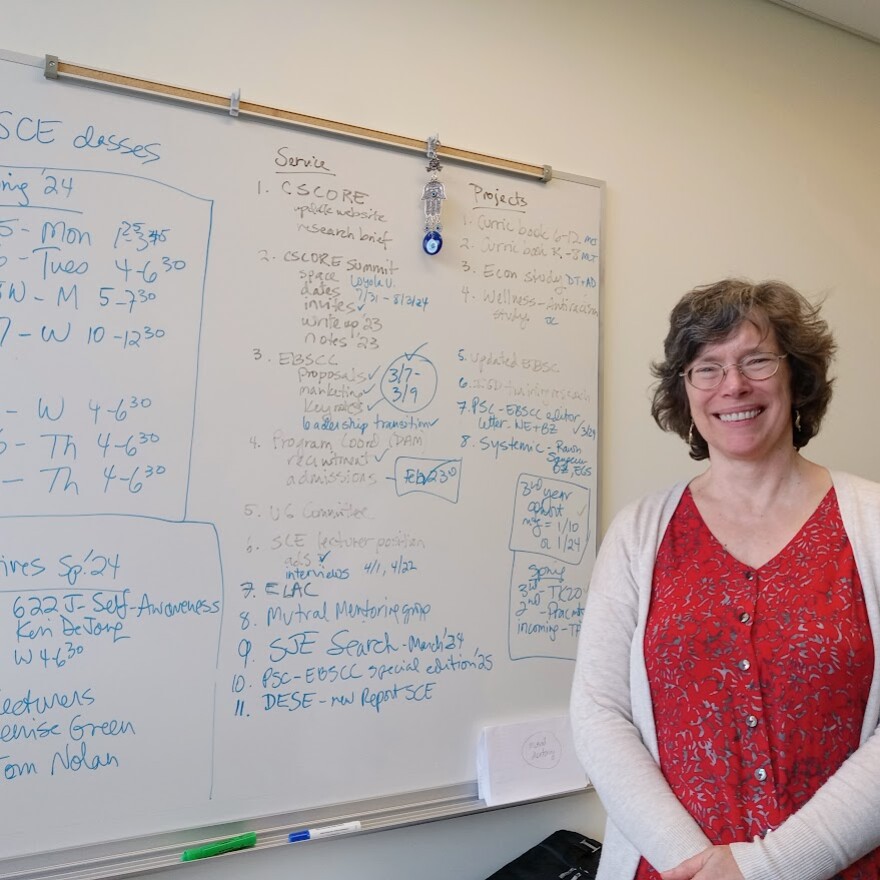

"You know, one school counselor for three rural elementary schools, where you're doing the job, but you don't really actually feel connected to a community," said Carey Dimmitt, director of the Center for School Counseling Outcome Research & Evaluation at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Another hurdle to attracting more young people to the field of education could be the necessary additional years of study. But Dimmitt said school counselors learn what it means to work as part of a team — using research to help young people.

"Assessing your outcomes, sort of demonstrating impact, not just having it be 'random acts of guidance,' as one of my colleagues says," Dimmitt said.

In this line of work, you have to be good with kids, Dimmit said, be deeply relational and able to think about changing the system so it works better for students. It's a specific set of skills and interests.

"Deciding to be a counselor or a teacher — really, there has to be an element of calling to it and I just don't think everyone's called to it," Dimmitt said.

Dimmitt also oversees the UMass Amherst graduate school counselor program, where students study pedagogy, trauma, clinical assessment and the juvenile justice system. When they finish and are looking for work, Dimmitt encourages students to look for a district that values their school counselors.

"Honors what they can do and what they know, rather than saying, 'Hey, you're going to have lunch duty every day,'" Dimmitt said.

That is the ideal, though it may not be the reality — especially at the start of a career and as school districts say they can't find or are forced to hire fewer teacher aides.

On a recent day at UMass Amherst, in a graduate-level practicum course, Deirdre Cuffee-Gray talked with her students about their future. Several were about to get their master's degree.

They spoke about their placements in western Massachusetts schools — about working with students and sometimes being asked to answer phones in the school office or other tasks that pull them away from their own work.

On this day, Cuffee-Gray, who is also a school counselor in the Amherst public school system, asked her students about job interviews.

“What about your experience on your site [helped you think about] what kind of site would be a good fit?" she asked.

A first-year school counselor may not find a perfect fit at the beginning of a career, though the starting salary is upwards of $60,000, more than most starting teachers make in Massachusetts.

When school counselor Colin Moge was working on his master's in education at Westfield State University, his internship placement was at West Springfield High School, where he now works.

The timing of his licensure coincided with a counselor's retirement, and Moge was hired.

On a spring morning, walking through a main hallway at the school, Moge greeted — in rapid fire — almost every student whose eye he caught.

“I try to say, 'Hi,' [to] as many as I see," Moge said.

Moge said the number of his students who show any interest in the field of education has been dwindling.

"There's been a growing interest in engineering, in welding, in carpentry. A few students, more this year than ever, have been interested in electrical apprenticeships," Moge said.

Rarely does a student mention becoming a school counselor. But when one mentions an interest in psychology or becoming a therapist, Moge said he may tell them about his own experience — how he almost dropped out of high school, how he started community college as an older student, and how he found his first job.

As his students well know, earlier this year MASCA named Moge the 2024 Massachusetts School Counselor of the Year.