At this time of year, seeing two guys stalking around a graveyard might conjure up some spooky images.

But, if you’re in Vermont, they may just be Scott Baer and Daniel Barlow, the artists behind a project called Green Mountain Graveyards.

Together, Baer and Barlow have a passion for photographing the beauty that can be found in cemeteries. Their work forms the basis of an exhibit now on display at the Vermont Historical Society in Montpelier. Their photographs illuminate four different eras in funerary art in Vermont's memorial spaces.

One of Baer’s favorite pieces is a crudely carved face, known as a "soul effigy," that dates from 1800 in East Hill Cemetery in Williamstown. The face looks puzzled, which Baer says is reflective of the uncertainty at the time about where people went when they died.

“It was not a guarantee that you would go necessarily to Heaven or to Hell. It was more of a hope and dream that they would go where they wanted to go.”

Most early Vermont gravestones did not feature Christian symbols such as crosses or angels. Instead, they were personalized reflections on the afterlife.

“Some of these artists back then were not the renowned Italians coming overseas to do their art,” according to Baer. “It was more like whoever had the tools and capability and wished to do the job.”

Baer and Barlow say they are always hunting for the "death’s head" carving, which is common in other New England states.

“When we find an older cemetery, we’re usually excited to find things like soul effigies, or even coffins carved into stones, which are an even rarer symbol.”

In the 1800s, gravestone art shifted to focus more on the idea of the soul going to heaven. Popular gravestone images included weeping willows and hands with index fingers pointing skyward to guide the deceased.

“This really reflected how Vermonters were viewing life and the afterlife,” explains Barlow.

The Green Mountain Graveyards exhibit also features grave stones with personal stories, like the tombstone of "Little Margaret," a 9-year-old girl whose lifelike engraving still moves visitors to leave pennies at her grave. Or that of Colonel James Fiske.

Barlow describes Fiske as "a robber baron, a businessman, married several times, ended up being murdered by a business partner. His monument in Brattleboro is surrounded by four statues of topless women. Each one is holding a symbol of his empire while he was alive. You can tell the ego of this man."

Also featured in the exhibit is the grave of John Bowman, who commissioned a mausoleum for the family he lost when he was very young.

“There are statues of his family inside the mausoleum, but there’s also a statue of him walking up the steps to the mausoleum with a key in hand to go join his family,” says Barlow. “It’s an amazing statue — you can really see the grief on his face. It really exemplifies his desire to go join his family in the afterlife.”

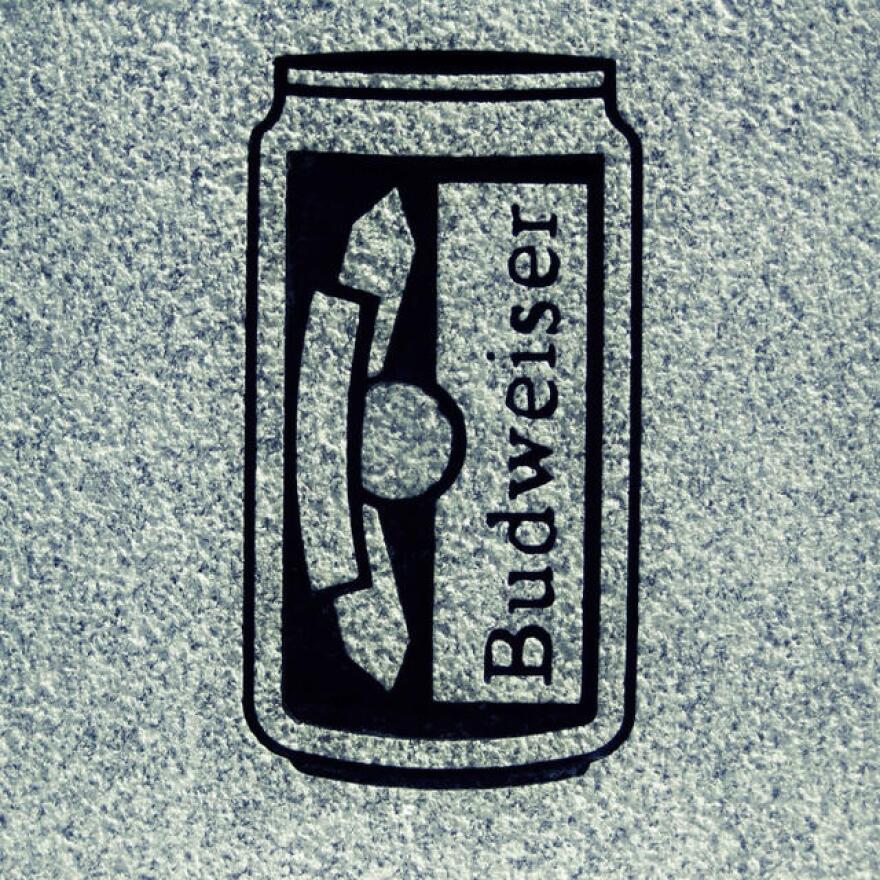

A more contemporary gravestone from Fairview Cemetery in East Callais features a Budweiser beer can carved onto the side of a granite block beside the gravestone. On top of the stone is a circular hole that functions as a beer cozy. Baer smiles.

“If you wanted to go and pay last respects to him on any given day, you could have a beer with your old departed friend.”

While the hobby might seem a tad macabre, Barlow says he sees graveyard photography as an under-appreciated art form in Vermont that raises important questions about the meaning of life, and what happens after we die.

“These are questions that we don’t as a society talk to each other very often about. The reaction we get from most people is that they have their own favorite cemetery, and they want to tell us about it, and they want us to go there and photograph it. People want to share their own experiences with cemeteries and graveyards with us.”

Broadcast live on Thursday, October 30th at noon; rebroadcast at 7 p.m.