When Nikita Khrushchev emerged as the leader of the Soviet Union after Stalin's death in 1953, one of the first things he addressed was the housing shortage and the need for more food. At the time, thousands of people were living in cramped communal apartments, sharing one kitchen and one bathroom with sometimes up to 20 other families.

"People wanted to live in their own apartment," says Sergei Khrushchev, the son of Nikita Khrushchev. "But in Stalin's time you cannot find this. When my father came to power, he proclaimed that there will be mass construction of apartment buildings, and in each apartment will live only one family."

They were called khrushchevkas — five-story buildings made of prefabricated concrete panels. "They were horribly built; you could hear your neighbor," says Edward Shenderovich, an entrepreneur and Russian poet. The apartments had small toilets, very low ceilings and very small kitchens.

But "no matter how tiny it was, it was yours," says journalist Masha Karp, who was born in Moscow and worked as an editor for the BBC World Service from 1991 to 2009. "This kitchen was the place where people could finally get together and talk at home without fearing the neighbors in the communal flat."

These more private kitchens were emblematic of the completely new era of Soviet life under Khrushchev. "It was called a thaw, and for a reason," says Karp.

"Like in the winter when you have a lot of snow but spots are already green and the new grass was coming," says Russian writer Vladimir Voinovich. "In Khrushchev times it was a very good time for inspiration. A little more liberal than before."

Kitchen Table Talk

The individual kitchens in these tiny apartments, which were approximately 300 to 500 square feet, became hot spots of culture. Music was played, poetry was recited, underground tapes were exchanged, forbidden art and literature circulated, politics was debated and deep friendships were forged.

"One of the reasons why kitchen culture developed in Russia is because there were no places to meet," says Shenderovich. "You couldn't have political discussions in public, at your workplace. You couldn't go to cafes — they were state-owned. The kitchen became the place where Russian culture kept living, untouched by the regime."

In a country with little or no place to gather for the free expression of ideas and no place to talk politics without fear of repression, these new kitchens made it possible for friends to gather privately in one place.

These "dissident kitchens" took the place of uncensored lecture halls, unofficial art exhibitions, clubs, bars and dating services.

"The kitchen was for intimate circle of your close friends," says Alexander Genis, Russian writer and radio journalist. "When you came to the kitchen, you put on the table some vodka and something from your balcony — not refrigerator, but balcony, like pickled mushrooms. Something pickled. Sour is the taste of Russia."

Furious discussions took place over pickled cabbage, boiled potatoes, sardines, sprats and herring.

"Kitchens became debating societies," remembers Gregory (Grisha) Freidin, professor of Slavic languages and literature at Stanford University. "Even to this day, political windbaggery is referred to as 'kitchen table talk.' "

Even in the kitchen, the KGB was an ever-present threat. People were wary of bugs and hidden microphones. Phones were unplugged or covered with pillows. Water was turned on so no one could hear.

"Some of us had been followed," says Freidin. "Sometimes there would be KGB agents stationed outside the apartments and in the stairwells. During those times we expected to be arrested any night."

Samizdat

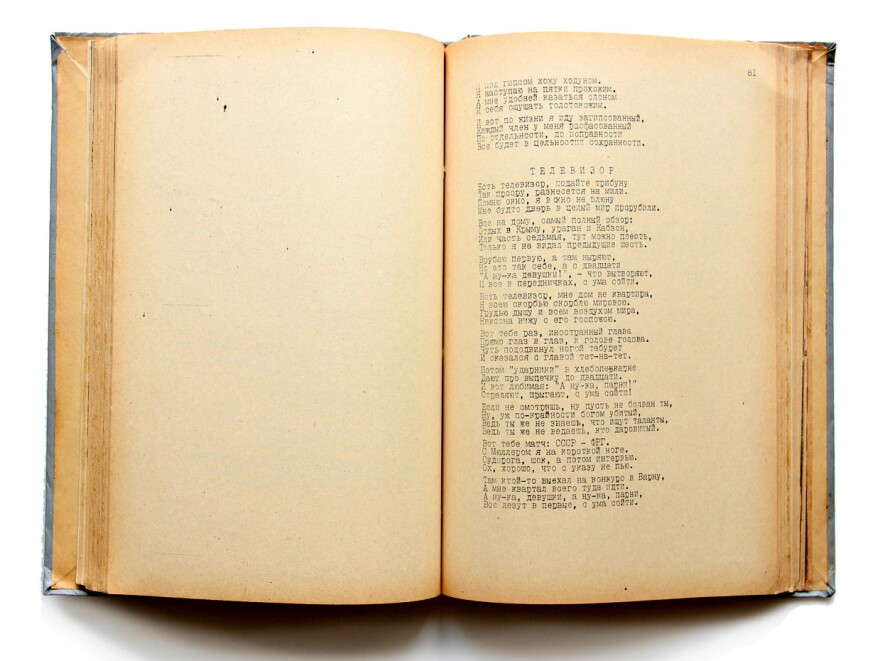

As the night wore on, kitchen conversations moved from politics to literature. Much literature was forbidden and could not be published or read openly in Soviet society. Kitchens became the place where people read and exchanged samizdat, or self-published books and documents.

People would type hundreds of pages on a typewriter, using carbon paper to create four or five copies, which were passed from one person to the next — political writings, fiction, poetry, philosophy.

"Samizdat is, I think, the precursor of Internet," says Genis. "You put everything on it, like Facebook. And it wasn't easy to get typewriters because all typewriters must be registered by the KGB. That's how people got caught and sentenced to jail."

"Samizdat was the most important part of our literature life," says Genis. "And literature was the most important part of our life, period. Literature for us was like movies for Americans or music for young people."

In 1973, Masha Karp's friend got hold of a typewritten copy of Boris Pasternak's Dr. Zhivago. "She told me, 'I'm reading it at night. I can't let it out of my hands. But you can come to my kitchen and read it here.' So I read it in four afternoons."

Genis' family read Gulag Archipelago, by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, in the kitchen. "It's a huge book, three volumes, and all our family sat at the kitchen. And we were afraid of our neighbor, but she was sleeping. And my father, my mother, my brother, me and my grandma — who was very old and had very little education — all sit at the table and read page, give page, the whole night. Maybe it was the best night of my life."

Magnitizdat

What happened with samizdat books happened with music, too. Magnitizdat are recordings made on reel-to-reel tape recorders. Tape recorders were expensive but permitted in the Soviet Union for home recordings of bards, poets, folksingers and songwriters, made and passed from friend to friend. People had hundreds of tapes they shared through the kitchens.

"My songs were my type of reactions to the events and news," says songwriter Yuliy Kim, one of Russia's famous bards, who was barred from giving public concerts. "I would write a song about whatever was discussed. I would sing it during the discussion. If there would be someone with a tape recorder they would tape it and take it to another party. Songs were spread quickly like interesting stories."

"The most famous bard was Vladimir Vysotsky, who was like Bob Dylan of Russia," says Genis. "That's what you can listen to in kitchen."

Bone Music

Before the availability of the tape recorder and during the 1950s, when vinyl was scarce, ingenious Russians began recording banned bootlegged jazz, boogie woogie and rock 'n' roll on exposed X-ray film salvaged from hospital waste bins and archives.

"Usually it was the Western music they wanted to copy," says Sergei Khrushchev. "Before the tape recorders they used the X-ray film of bones and recorded music on the bones, bone music."

"They would cut the X-ray into a crude circle with manicure scissors and use a cigarette to burn a hole," says author Anya von Bremzen. "You'd have Elvis on the lungs, Duke Ellington on Aunt Masha's brain scan — forbidden Western music captured on the interiors of Soviet citizens."

Radio: 'A Window To The Freedom'

Most kitchens had a radio that reached beyond the borders and censorship of the Soviet Union. People would crowd around the kitchen listening to broadcasts from the BBC, Voice of America and Radio Liberte.

"It was part of our life in the kitchen," says Vladimir Voinovich, author of The Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Private Ivan Chonkin. "It was a window to the freedom."

Voinovich's books were circulated in samizdat and smuggled out of the country. One of his pieces was broadcast by a foreign radio station. "I heard some BBC voice reading my chapters. After that I was immediately summoned to KGB." Voinovich was expelled from the Writers Union and later forced to emigrate.

Moscow Kitchens

Dissident composer Yuliy Kim wrote a cycle of songs called "Moscow Kitchens" telling the story of a group of people in the 1950s and the '60s called "dissidents." It tells how they began to get together, how it led to protests, how they were detained and forced to leave the country. He describes the kitchen:

"A tea house, a pie house, a pancake house, a study, a gambling dive, a living room, a parlor, a ballroom. A salon for a passing by drunkard. A home for a visiting bard to crash for a night. This is a Moscow kitchen, ten square meters housing 100 guests."

And, he adds: "This is how this subversive thought grew and expanded in the Soviet Union, beginning with free discussions at the kitchens."

Additional features, photos, recipes and music can be found at kitchensisters.org.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDIxMDkyNjUxMDE0NDY1Njg1NzRiOTRiYQ000))