Some milestone moments in journalism converged 60 years ago on election night in the run between Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower and Democratic Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson. It was the first coast-to-coast television broadcast of a presidential election. Walter Cronkite anchored his first election night broadcast for CBS.

And it was the first time computers were brought in to help predict the outcome. That event in 1952 helped usher in the computer age, but it wasn't exactly love at first sight.

The 'Electronic Brain'

CBS' Charles Collingwood was the reporter assigned to UNIVAC, one of the world's first commercial computers.

"This is the face of a UNIVAC," Collingwood told the CBS audience. "A UNIVAC is a fabulous electronic machine, which we have borrowed to help us predict this election from the basis of early returns as they come in."

The "face" Collingwood refered to was just the console. He sat in front of a mock-up of the console in New York. It was the size of a large desk, with something that looked like a blinking bookcase sitting on top. The real UNIVAC, which took up the better part of a room, was nearly 100 miles away in Philadelphia with its programmers and a CBS camera crew.

"It's there with its operator," Collingwood said. "On the right of the UNIVAC, there's something which looks like a typewriter. That's the way UNIVAC talks."

This explanation was rudimentary but the general public had never seen a computer work a live event before. And Collingwood was trying very hard to personify what was being called an "electronic brain" with lines like: "He's sitting there in his corner humming away."

Ira Chinoy, associate dean of journalism at the University of Maryland, wrote a dissertation examining the introduction of computers on election night entitled: Battle of the Brains: Election-Night Forecasting at the Dawn of the Computer Age.

"It was by no means a done deal that computers should be a technology used in news in any way, let alone on election night," Chinoy says.

For CBS, using a computer was a bit of a gimmick — a sideshow. But for Remington Rand, the company that made the UNIVAC, this was an enormous gamble.

"There was a clear awareness that if they messed this up on election night, it might set their nascent industry back quite a bit," Chinoy says.

And there was good reason for worry. Early in the evening things weren't going well for UNIVAC.

"Have you got a prediction for us, UNIVAC?" Collingwood asked.

There was no response. The typewriter didn't move and to the audience at home the UNIVAC must have looked like a big, dumb box.

"You're a very impolite machine I must say," Collingwood said. "But he's an awfully rapid calculator."

An Unlikely Result

This was the common scenario during the few times Walter Cronkite actually turned to Collingwood and the UNIVAC that night. But behind the scenes in Philadelphia not everything was as it seemed. The UNIVAC did make a prediction, but someone held it back. Most likely, it was the computer programmers themselves, and the most likely reason: because the prediction seemed so ridiculous.

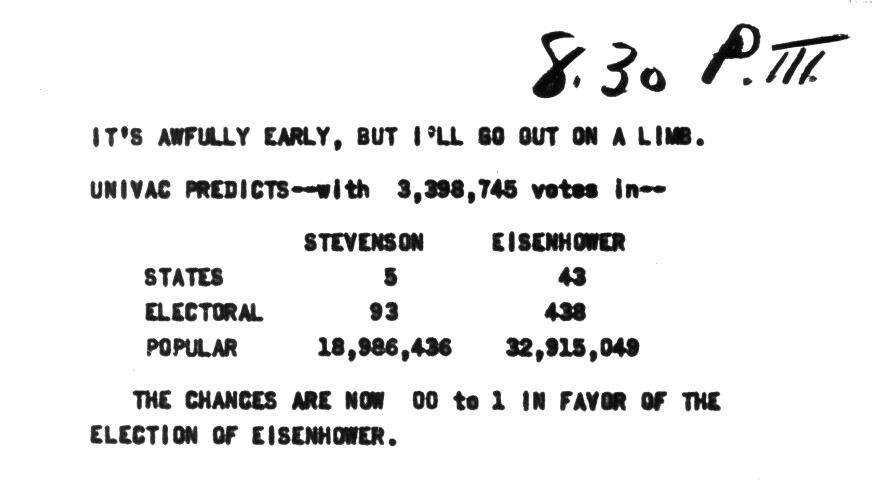

Before election night 60 years ago, the race between Stevenson and Eisenhower looked close. But early in the night, with just over 3 million votes counted, UNIVAC predicted the odds were 100 to 1 in favor of Eisenhower.

Even early returns, without the aid of a computer, were indicating an Eisenhower landslide. But the odds still seemed inconceivable. The computer printout, revealed hours later, read: "It's awfully early, but I'll go out on a limb ... The chances are now 00 to 1 in favor of the election of Eisenhower." The printout read 00 instead of 100 because the programmers never imagined needing an odd greater than two digits.

It wasn't until after midnight that a Remington Rand representative, Art Draper in Philadelphia, came on the air with an explanation.

"As more votes came in, the odds came back and it was obviously evident that we should have had the nerve enough to believe the machine in the first place," he said. "It was right. We were wrong. Next year we'll believe it."

A Cultural Icon

UNIVAC's early "faltering" turned into a publicity coup for the company. Some newspapers later carried headlines like: "A Machine makes a Monkey out of Man." And UNIVAC became a cultural icon.

"It became synonymous with the product — like Kleenex and Xerox and Scotch Tape," says Alex Bochannek, a curator at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif.

The UNIVAC showed up on the cover of a Superman comic book. A Warner Bros. cartoon had Wile E. Coyote build one to help him capture the elusive Bugs Bunny.

But there was often an undercurrent of mockery, a hint that this supposedly all-knowing machine wasn't quite what it was cracked up to be.

"This idea of calling them Giant Brains gave them a lot more credit than they really deserved back then," Bochannek says. "They didn't have quite the brain capacity a lot of people attributed to them."

The Computer History Museum has one of the few remaining original UNIVAC consoles on display. It's a large panel propped on top of a 1940s-era steel desk with a keyboard. An operator used the keyboard to send instructions directly to the computer.

Much of the system was housed in a cabinet big enough for a person to walk in. There were more than 5,000 vacuum tubes and tanks of mercury (Mercury Delay Lines) where data was stored as sound waves for memory. But UNIVAC also had rows of magnetic tape drives for long-term storage.

"That is what really made this machine so useful to businesses," Bochannek says. "You had tapes with large capacity, which wasn't really available on these early computing devices."

Man Vs. Machine

Back in 1952, NBC also used a computer on election night: the Monrobot. It was much smaller than UNIVAC and less powerful, but it didn't falter on its prediction of an Eisenhower landslide. Still, says Chinoy, ambivalence about using a computer on election night continued for much of the decade.

"The way we think about technology, if we look in the rearview mirror," he says. "They march in, they became a fixture on election night and that's it. NBC actually backed away from using a computer in 1954 and decided a good reporter is better than any kind of statistical device."

Yet, all three networks were using computers by the next presidential election in 1956. ABC, however, staged a challenge: "Man vs. Machine."

The network invited pollster Lou Harris and a team of 100 reporters in the field to compete against a computer, Underwood's Elecom, to see who could call the election first. Again, it was a matchup between Eisenhower and Stevenson.

When it came to crunching numbers, the computer was untouchable, but the predictive models used in its programming were simplistic. UNIVAC was taking the early raw vote count and making comparisons with some past presidential elections.

Harris, who based his prediction on specific voting districts that he thought would mirror the overall outcome, tallied results with slide rules. His team won. And incumbent Eisenhower won by an even bigger landslide than in '52.

"Basically patterns emerge from data," says Harris, now 91. "If you can't read them right, then you can't tell the story."

Improving The Technology

Harris wondered if computers could do better. So he spent time at IBM, which by now had become the industry's leader. There, Harris pushed the IBM programmers to create more sophisticated election night software.

"I said, 'Look, I've got to get the computer to print out this, this and this,' " Harris says. "And they said, 'Good Lord.' It was multiple dimensions versus simple dimensions."

Harris, who had been John Kennedy's pollster for the 1960 presidential race, was contracted by CBS for the 1962 midterm elections. Harris, and his computer-generated predictions, were fed to Cronkite.

"He said to me after we made the first prediction, he said, 'Lou you better be right. My whole future depends on it.' I said, 'Walter, I'm sure it will be,' " Harris says.

Cronkite was calling race after race before anyone else, including the Michigan governor seat for George Romney. It was quite a coup because the returns, two hours after the polls closed, had Romney behind Democratic incumbent John Swainson.

The only governor race Harris couldn't call was in Massachusetts. And that vote resulted in a recall. Harris has been credited with coining the phrase "too close to call" that election night in 1962.

The Computerized Future

Although NBC walked away with more ratings share for its popular Huntley-Brinkley team, there was no doubt about who really won that night.

"This was a huge triumph for the then newly created CBS News election unit," says Martin Plissner, author of The Control Room: How Television Calls the Shots in Presidential Elections.

Plissner joined CBS in 1963 and was the network's political director for more than three decades. Newsrooms, he says, were no longer questioning the value of computers on election night.

"They understood that the quality of the information they were getting out of it depended considerably on the quality of the information they were putting into it," he says.

In the last 60 years there have been election night disasters, but when the information was good and the programming was clever, computers could be immensely powerful tools.

In retrospect, Chinoy says, it may be hard to understand why computers didn't "march in" and take a central place immediately on election night 1952.

"New things engage us and also scare us," he says. "We're drawn to them, but they're disruptive."

You can see that on the CBS broadcast 60 years ago.

"This is not a joke or a trick," Collingwood told his television audience, "It's an experiment. We don't know. We think it'll work. We hope it will work."

In the end, it did. And of course, computers were also getting faster, more powerful. Big hulking early computers like the UNIVAC were shrinking. By the late 1960s, tiny electronic circuits, or microchips, would transform the industry and computers would begin to find their way into all of our lives.

Produced by Cindy Carpien.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDIxMDkyNjUxMDE0NDY1Njg1NzRiOTRiYQ000))