Key takeaways

Chapter One: Two Abenaki First Nations, headquartered in Quebec, contest the legitimacy of the groups that the state of Vermont recognizes as Abenaki tribes — a conflict that has its roots in disputed historical narratives. [Listen Now]

Chapter Two: That disputed history is partly why Vermont’s groups failed to get federal recognition. But about a decade ago, Vermont set up its own process and recognized four tribes: the Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi, the Elnu Abenaki Tribe, the Koasek Traditional Band of the Koas Abenaki Nation and the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuck Abenaki Nation. A key aspect of the groups' argument is that Abenaki peoples hid for nearly 200 years in Vermont, in part to avoid statewide eugenics policies. But recent evidence casts doubt on this narrative. [Listen Now]

Chapter Three: Today, the state and the groups it recognizes as Abenaki tribes have a different definition of what it means to be Indigenous, compared to many Indigenous Nations in the U.S. and Canada. And that matters, because there is power, authority and money at stake. Now, the First Nations in Canada are calling for a reexamination of Vermont's recognition process. [Listen Now]

Chapter One

Note: Our show is made for the ear. We recommend listening to the audio provided here. But we also provide a written version of the episode below.

To learn more about our approach to this story, you can read our editor's note, here.

Loading...

Josh Crane: From Vermont Public and the NPR Network, this is Brave Little State. I’m Josh Crane.

Elodie Reed: And I’m Elodie Reed.

For the past 20 years, there's been this controversy in Vermont.

But for most of that time, it’s felt sort of hush-hush. Many people don't really like talking about it. Some would rather avoid acknowledging it's there in the first place.

But in the last couple years, it's gotten harder to ignore. More and more people have been speaking out.

Philip Brett: Her grandfather is in the picture.

Denise Watso: No he’s not.

Philip Brett: Yes he is.

Elodie Reed: One afternoon this spring, a dozen people form a circle in a dusty parking lot, hunched against a chilly breeze.

Claude Panadis Jr.: It’s cold! It snowed at home this morning.

Elodie Reed: They’re standing outside the Ethan Allen Homestead Museum in Burlington. Ethan Allen is a celebrated figure in Vermont’s colonial history — or, not-so-celebrated.

Richard Witting: So the Allens, they were the lead family who, like, essentially surveyed most of the land in Vermont and like, acquired it, and then resold it.

Denise Watso: So more land grabbers?

Richard Witting: I mean, he's the number one land grabber.

Elodie Reed: Most of the people gathered in this parking lot drove down from Canada or up from Albany, New York.

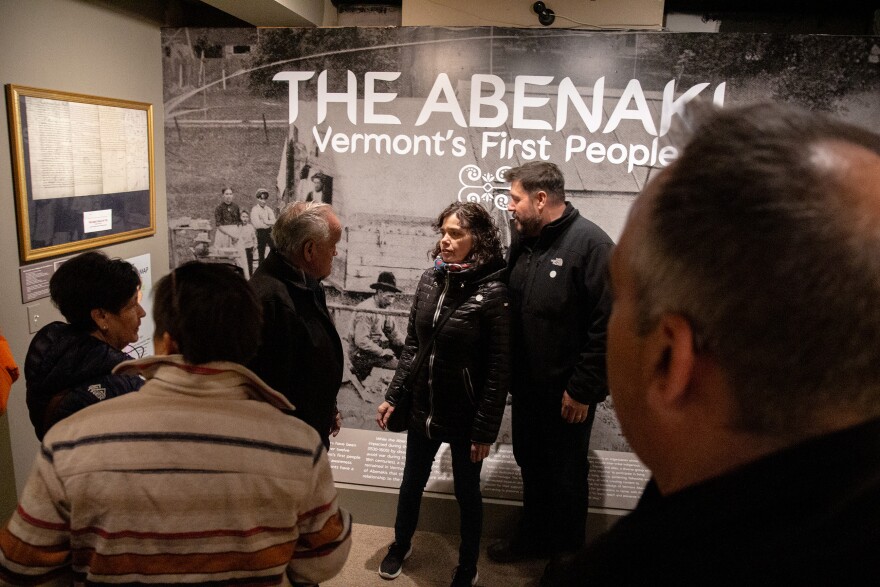

But they’re not actually here to take issue with Ethan Allen. They’re here to protest an exhibit inside the building called “The Abenaki: Vermont’s First People.”

It was curated by a Vermont nonprofit, Alnôbaiwi, which says it’s dedicated to preserving Vermont Abenaki heritage.

And here’s one more twist: These protesters, here to take a stand against a history exhibit dedicated to Abenaki heritage? They’re Abenaki.

Claude Panadis Jr.: We all came from Odanak just to make sure that we can see what’s going on and see if we can’t get our voices heard.

Elodie Reed: If you live in Vermont, you’ve probably heard of the Abenaki — they’re the original caretakers of the land now known as Vermont and New Hampshire, and also Quebec, Maine and Massachusetts. The groups you’re probably most familiar with are those that have been recognized by our state as Abenaki tribes. What you might not know is that there are Abenaki First Nations north of the border, in Canada. They have a very different type of recognition: federal recognition, from the Canadian government. They’re called Odanak First Nation and Wôlinak First Nation. Both Nations are headquartered in Quebec, and they’re both Western Abenaki.

Some people say it uh-BEN-uh-KEE, with the French pronunciation. We’re using the more Anglicized “AH-ben-ACK-ee.”

Denise Watso: That’s the incompetence of this museum.

(unintelligible conversation)

Elodie Reed: Today, gathered in the Ethan Allen Homestead Museum parking lot, are citizens and allies of Odanak.

Claude Panadis Jr.: It’s family. Family is so important and cultural appropriation is a serious matter.

Elodie Reed: The thing they’re here to protest is the use of a single photograph in this Abenaki history exhibit. It’s from a 1906 postcard, which is captioned with the words: “Indian Camp, Highgate Springs, Vermont.” It has been enlarged and printed on a wall of the exhibit.

The photo is black and white. It shows women and children in the background, standing by the door of a cabin. In the foreground, a man in a hat holds a pan over a fire. And who that man is — and who he’s related to — are the main points of contention.

On one side are the Odanak First Nation government and some of its citizens, saying the man in the image is related to the Panadises — a well-established Abenaki family.

On the other, you have the Vermont nonprofit Alnôbaiwi, saying the man in the image is related to one of the curators of the exhibit, Holly LaFrance. She belongs to one of the groups that the state of Vermont recognizes as Abenaki.

Denise Watso: They’re claiming Holly LaFrance in front of their family photo saying that she’s related — "that’s my ancestor." It’s a joke.

Elodie Reed: LaFrance isn’t here on this chilly spring day. And she has declined to be interviewed. Instead, volunteers from Alnôbaiwi wander out from the museum and into the parking lot, where Odanak citizens and some allies are circled up.

Within seconds, the arguing begins.

Denise Watso: Who are you, sir?

Philip Brett: I’m Philip Brett. ... What I am here to say is Holly has a picture of her grandfather in that picture. So you have basically proven that Holly is related to the Panadis family. Thanks.

Denise Watso: This is all the Panadis family. So you tell me they say—

Philip Brett: Well, good, she is related to the Panadises then.

Denise Watso: No.

Daniel Nolett: This is her genealogy, where do you see a family name in there — it goes back four generations.

Philip Brett: It’s not— It’s not clear yet.

Denise Watso: Right. Then don’t stand in front of their family photo and claim that it is if it’s not clear.

Philip Brett: Her grandfather is in—

Denise Watso: If it’s not clear then don’t stand in front of the photo.

Philip Brett: Her grandfather is in the picture.

Denise Watso: No he’s not.

Philip Brett: Yes he is.

Denise Watso: No he’s not.

Philip Brett: Her grandfather is in the picture.

Elodie Reed: There’s no way for me to say, with 100% certainty, who the man in this century-old photo is. I emailed the two places the image is publicly available — the special collection library at the University of Vermont, and the Vermont Historical Society. Neither had identifying information.

So.

This fight over who is in a photograph on the wall of a museum exhibit in Burlington, it’s a microcosm of this controversy playing out around Vermont and beyond.

And it illustrates a lot of the tensions and frustrations baked into this situation. Emotions are high. People are upset.

Because this is really a fight over whether Vermont — and its state-recognized tribes — should decide who is Abenaki. And Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations, federally recognized tribes in Canada, don’t think they should.

This is a dispute that goes back at least two decades. But it didn’t really come into public view until 2022, at an event held at the University of Vermont.

Jacques Watso: I wanted to acknowledge friends of Odanak that came here today.

Elodie Reed: It was a symposium sponsored by UVM’s history department, described as featuring, quote, “unheard Abenaki voices from the Odanak First Nation.”

At that event, Abenaki citizens who belong to Odanak First Nation in Canada came to Vermont and said that the state-recognized tribes here are made up of people who aren’t really Abenaki.

Jacques Watso: They sell fake Native arts jewelry. They write books, they do conferences. They use the fishing and hunting rights that are treaty rights meant for real Abenaki. They distort our culture and language beyond recognition. They are erasing us by replacing us.

Elodie Reed: Members and allies of Vermont’s state-recognized tribes said these accusations hurt.

Jeff Benay: I'm getting calls, because we've got kids at UVM. Abenakis at UVM. And the concern is “Are we safe at University of Vermont?” Because if they weren't actually at this event, they heard. And they heard that the way the American Aben— the Vermont Abenaki were castigated.

Elodie Reed: The UVM event was the first time I — and many others — heard this sentiment shared so directly and publicly. But I’d heard whispers about this ever since starting to report agriculture stories for Vermont Public a few years ago. As soon as I started building relationships with sources involved in Indigenous issues, this question of legitimacy came up.

And I’ll just say here: I’m not Indigenous. But I have been the primary person reporting on this story in our newsroom. And through this reporting, we have learned from a number of Indigenous sources and experts that being Indigenous is different from other forms of identity, such as race or gender.

While there is not a universally agreed-upon definition of what it means to be Indigenous, one common understanding is that it is a political identity. Basically, that you’re a citizen of an Indigenous Nation in addition to being a citizen of the U.S. or Canada. And that it is up to each Indigenous Nation to collectively determine who belongs and who does not.

But this gets complicated when it comes to Vermont’s state-recognized tribes. Because as we’re going to discuss in this story, they differ — a lot — from many Indigenous Nations. Not just because they’re recognized at the state level, which is relatively uncommon, but also because of how some of their members, and even leaders, define what it means to be Indigenous.

Rich Holschuh: There are all kinds of lived experiences. We are not less than, here. We are different.

Elodie Reed: And that difference is central to the question of legitimacy.

Not everyone thinks we should be covering this controversy. We’ve experienced strong pushback on the stories we’ve published since the UVM event in 2022.

Don Stevens: There's also responsible journalism — and yes, I'm looking at you Elodie. To keep a one-sided narrative, for whatever reason that is, to just concentrate on Odanak’s issue and not be responsible in the journalism, for balance.

Elodie Reed: But in our reporting prior to that 2022 UVM event with Odanak citizens, we excluded both Odanak First Nation and Wôlinak First Nations, and their criticism of Vermont’s state-recognized tribes.

Josh Crane: For instance, you might remember this Brave Little State episode about Abenaki peoples from 2016:

Bethany Ladimer: What is the status of the Abenaki Native Americans in Vermont today?

Angela Evancie: We brought Bethany’s question straight to some of the people who can answer it best.

Josh Crane: That episode focused on Vermont’s state-recognized tribes, and their increasing visibility.

Shirly Hook: We’ve been here forever and they just recognized us.

Amy Hook-Therrien: People kept saying that there were no Natives in Vermont and everything like that, and then finally it was like, ta-da! Yeah there are.

Josh Crane: Well, the status of Abenaki peoples in Vermont today is more complicated and contentious than we’ve previously reported.

Elodie Reed: And some of you have been wondering about it, too.

Jenny Prince: My name is Jenny Prince. And I'm wondering what it means that the Odanak Abenaki First Nation of Quebec recently denounced all Vermont and New Hampshire tribes due to self Indigenization.

Josh Crane: Right around the time Elodie started her reporting on this issue, we got this question from Jenny Prince.

Elodie Reed: Prince lives in the Champlain Islands, and she is not Indigenous herself.

Josh Crane: She says she submitted this question to the show because she’d heard about this dispute, and it wasn’t getting a ton of media attention at the time.

Jenny Prince: I wanted to encourage Brave Little State to talk about this, because I think that within Vermont, it has been a really sensitive subject. And it hasn't been something that maybe a lot of people really welcomed. I think that Vermonters are protective of the Abenaki identity — white Vermonters, non-Abenaki Vermonters.

Josh Crane: This conflict is connected to a long history.

Mali Obomsawin: We didn't travel here from somewhere else, we emerged here.

Elodie Reed: Both for Indigenous peoples, and settlers.

Philip Deloria: White Americans have dressed up, played Indian over time, from the revolution to the present day.

Josh Crane: And it’s connected to a disputed history.

Mitch Wertlieb: For the original Vermonters, the Abenaki, eugenics and racial prejudice led to a life lived in the shadows.

Suzie O’Bomsawin: We never lived in hiding. This is not something I would like the next generation to read about.

Elodie Reed: It’s also related to a fundamental disconnect over what it means to be Indigenous.

Chawna Cota: I felt a sense of connection to that ancestor, who gave me that sense of connection to the land.

Kim TallBear: When it moves from being about a people, a Nation, a collective and defending their land and place-based rights, to defending your own individual rights based on some ancestral claim, that's a total problem.

Josh Crane: Part of the conflict is about whether the state of Vermont should be recognizing groups as Indigenous in the first place.

Vince Illuzzi: I don't think these people were coming forward for state recognition for any reason other than that they were of Abenaki descent and wanted to preserve their culture.

Elodie Reed: This is a conflict with money and power at stake.

Rich Holschuh: It's really clear to me that this is politics. And politics is about power and control.

Josh Crane: But also the right to be viewed as an authority on your community’s story.

Denise Watso: And I've heard this over and over, “We just want to honor you.” Well, to honor us is to listen to us, listen to what we are saying.

Elodie Reed: This is a story for anyone who wants to understand the deeper context of this controversy: from the history to the ongoing tension. Whether you’re a citizen of Odanak or Wôlinak First Nations, a member of Vermont’s state-recognized tribes, or neither.

Josh Crane: There’s so much to cover that we’re breaking it up into three episodes.

Welcome to “Recognized” — a special series from Brave Little State.

This is Chapter One. And a quick note here, that all three chapters of this story cover sensitive material, including some slurs. Listen with care. We’ll be right back.

Oldest stories

Elodie Reed: The story of Abenaki peoples is, broadly speaking, agreed upon until the year 1800 or so. In a way, that’s when this dispute begins — with disputed history.

But first: The word “Odanak” means “in the village” — and it’s a location that has been significant to Abenaki peoples for many generations, long before the year 1800. And long before any Europeans showed up on the continent.

So: Let’s take a road trip to Odanak.

Julia Furukawa: Good day. How are you, Elodie?

Elodie Reed: Better with coffee.

Elodie Reed: I met up with a reporter from New Hampshire Public Radio, Julia Furukawa, on a very cold day last winter.

Elodie Reed: Can't believe you got iced coffee, it’s 10 degrees out.

(sound of ice in a cup)

Julia Furukawa: The sound of success.

Elodie Reed: We woke up very early.

Julia Furukawa: So I was technically awake at five.

Elodie Reed: And drove up to Odanak First Nation’s reserve in Quebec.

Elodie Reed: From the Vermont-Canada border crossing in Highgate Springs, Odanak is pretty much a two hour drive straight north. The reserve is right next to the Riviere Saint-Francois, or the St. Francis River. On that river bank sits Quebec’s first-ever Aboriginal museum institution, the Musée des Abénakis.

We visit the museum with Odanak First Nation’s assistant general director, Suzie O’Bomsawin.

She leads us towards a brick building.

Suzie O’Bomsawin: So this is the museum.

Elodie Reed: And she points out the museum is housed in the former Indian day school.

Suzie O’Bomsawin: It was a Catholic school, they were being taught in French. My grandfather went there. My great grandfather went there. Yeah, they were teaching about making sure they are going to be good civilian.

Elodie Reed: In other words:

Suzie O’Bomsawin: Taking away their Indian identity to make sure they fit into the Canadian society.

Elodie Reed: We walk inside the former-school-turned-museum, which is full of kids on a field trip. There’s a giant map of the Northeast near the entrance. That’s where Suzie begins our tour.

Suzie O’Bomsawin: So usually the tour of the museum start with the, like some words related to the territory, Ndakina.

In English, Ndakina means “our territory.”

Suzie O’Bomsawin: Our territory used to go all the way down to what is today Boston. And of course, Lake Champlain was part of our territory.

Elodie Reed: Lake Champlain is where Suzie says all of Abenaki history begins.

Suzie O’Bomsawin: Lake Champlain is actually our birthplace. According to the creation story of the Nation. We were made out of stone first, and then because it was not good enough, we were then made out of black ash. And this is why black ash is so important to us as a Nation.

Elodie Reed: This creation story can give you a sense of just how long Abenaki peoples — or known by another name, Wabanaki peoples, or “people of the dawn” — have been here, in this place.

Mali Obomsawin: We didn't travel here from somewhere else, we emerged here.

Elodie Reed: This is Mali Obomsawin. She’s a citizen of Odanak First Nation who studies Abenaki history.

Mali Obomsawin: From that time, we spent generations and generations learning how to live here in these homelands.

Elodie Reed: And Mali Obomsawin, by the way, is only distantly related to Suzie O’Bomsawin — O’Bomsawin is a pretty common Abenaki last name.

Mali Obomsawin: We developed an incredible system of understanding the moon cycles, and there's lots of stories attached to that. And we have all our cultural heroes like Glooscap.

Elodie Reed: Mali says Glooscap is the first human and first Wabanaki.

Mali Obomsawin: And so Glooscap is hilarious, because he just kind of goes around, messing up, making mistakes and doing things like taking the easy way out and like having to learn over and over why it's important to, I guess, act with intention. He learns lessons for us, so that we have something to hold on to and make reference to in the way that we live our lives.

Elodie Reed: In addition to holding lessons, Mali says Wabanaki stories can give important information about the geological time periods during which Abenaki peoples have been here.

Mali Obomsawin: Some of our oldest stories talk about the time when the people learned that there was going to be an ice age. We also have stories about megafauna, like giant beavers, which we also know through Western science did exist here.

Elodie Reed: Archeological digs have also verified stories about Abenaki peoples going to Odanak. Here’s Suzie O’Bomsawin again.

Suzie O’Bomsawin: With the diggings, we can actually say that that site was a site that was already known to Abenaki people before colonization, and it was for thousands of years.

Having proof of that was just so much comfort. Like now it's clear like, we are not refugees, we knew that place before.

Elodie Reed: Prior to colonization, Abenaki peoples weren’t just clustered at Odanak — they lived all throughout their territory. Back to Mali Obomsawin.

Mali Obomsawin: And we moved following the food, but also following and maintaining complex trade economies. And that would also be conducted through the waterways. And we knew a lot about the cultures surrounding us, our brother Nations and our ally Nations.

Elodie Reed: Fast-forward to the early 1600s. Mali says there was some warfare among nations during a period of what was likely food scarcity. Also happening at that time:

Mali Obomsawin: With the arrival of Europeans was the Great Dying.

Elodie Reed: Disease. Warfare. Enslavement and slaughter. One study shows the Indigenous population in the Americas declined by 90%, from 60 million people to only 6 million, in the first century after the arrival of Europeans.

Mali Obomsawin: And that is what really started to cause a lot of the great migrations and displacements and disruptions and whatnot, the lifeways at that time.

Elodie Reed: Abenaki peoples began moving out of places like Vermont and New Hampshire and into the northern parts of their territory, in modern-day Quebec. French colonists began setting up mission villages there. Among them were Odanak and Wôlinak, and Mali says these would become a place of refuge for permanent settlement, as well as temporary relief during colonial warfare.

Mali Obomsawin: At home, at Odanak and Wôlinak, we are still the stewards of those homelands. We never ceded those territories. But we did take refuge from the warfare and the genocide that was targeting us. I think our ancestors decided that it was easier to stay alive on the north side of what would become the border.

Elodie Reed: This brings us to the year 1800. Odanak and Wôlinak say their ancestors had left what is now Vermont and New Hampshire by then. And in the years following, they would visit and move back into southern areas of their territory, and places beyond, like the Adirondacks and the Capitol Region areas of New York.

Mali Obomsawin: And so we would travel down, and we also became economically dependent on trading with settlers. Right? And we also continued to go down and visit our relatives … in these various outposts that were created in that period from the 1800s and the 1900s.

Elodie Reed: Among those outposts was Thompson’s Point in Charlotte, Vermont. A 1954 newspaper article in the Burlington Free Press says seven or eight Abenaki families were living in tents at the turn of the 20th century. Among them were brother and sister William and Marian Obomsawin — there’s that name again. Their father, the newspaper article said, initially paddled to the spot by canoe, and later brought his kids from Canada after he’d built a house.

Nearly 50 years later, the Free Press story said the Obomsawins were the last living Abenakis at Thompson’s Point.

Recordings that an anthropologist made of the Obomsawins in 1956 are kept in Dartmouth College’s Rauner Special Collections Library. That’s in Hanover, New Hampshire.

Mali Obomsawin recently studied for a research residency there, and she brought me one day this past spring.

Mali Obomsawin: And you’re with me, so you’re cool.

Elodie Reed: Inside the library, I ask Mali to play a recording of William Obomsawin.

Mali Obomsawin: Hopefully we won’t be too disruptive.

Elodie Reed: We’re including it here with permission from Odanak First Nation. In it, William Obsomsawin repeats a story passed down over many generations.

William Obomsawin: Shelburne Bay, where the British tried to cross the lake there. Where the British landed down there.

Gordon Day: Shelburne Point?

William Obomsawin: Shelburne Point, yes.

Mali Obomsawin: Pause it for a second. What he's talking about is like the American Revolution, right? And when there started to be all this action in the area around Lake Champlain, where we were currently living at the time, right?

Elodie Reed: As we listen to archival recordings, Mali and I are sitting at a desk, surrounded by giant boxes of papers kept by Gordon Day. Day was a non-Indigenous anthropologist known for doing in-depth study of Abenaki peoples. And Mali is looking for something.

Mali Obomsawin: I’m just looking for a specific thing. It’s in the ’70s.

Elodie Reed: The 1970s: when this historical narrative we’ve talked about so far is challenged. For the first time, members of what would become Vermont state-recognized tribes started saying that in fact, whole communities of Abenaki peoples stayed behind in Vermont and New Hampshire after 1800.

Mali Obomsawin: And he starts getting letters from his friend who's an attorney. And the attorney is like, “Please give me information on what's happening in Swanton. Who are these people?” basically.

Elodie Reed: What was happening in Swanton? That’s when we come back.

A new story

Elodie Reed: The story, for centuries, was that Abenaki peoples fled north, across the Canadian border to the reserves in Quebec. Then, from there, they occasionally visited or moved back to more southern outposts.

But in the 1970s, you start hearing that Abenaki peoples actually stayed south of the Canadian border the whole time, secretly living among the white settlers that surrounded them.

This version of history — it took hold thanks in large part to a man named Homer St. Francis.

Homer St. Francis: Today, I'm not in a very good mood because I got a word that they even shot down our ABE grant, because they’re afraid the Abenaki is getting too educated for them.

Elodie Reed: Here St. Francis is speaking at the since-closed Burlington College in 1989. He’s talking about how the state of Vermont is marginalizing its original inhabitants.

Homer St. Francis: They don't want them to have a high school diploma or a GED or anything else. They want to force them into the slave market. But it's country while they're not going in the slave market for this country. We will survive, we survived for 1,000 years, we will survive again.

Elodie Reed: Homer St. Francis is a big reason why we’re talking about Abenaki peoples in Vermont at all. He was really good at saying things that made people take notice.

Homer St. Francis: The people in this so-called state are fed up with bureaucratic bulls***.

Elodie Reed: His name began popping up in newspaper articles in the mid-1970s as part of a group in the Swanton-Highgate area of northwestern Vermont. The group was saying they were Abenaki, that they had always been in Vermont, and that they, therefore, had rights to land, as well as free hunting and fishing.

This was happening at the same time as the nationwide Red Power Movement — Indigenous peoples all over the country were fighting for the federal government to honor treaties promising sovereignty and land and water rights.

NPR Longest Walk coverage: Hundreds of American Indians marched on the Capitol today. They are part of the Longest Walk, a 3,000-mile march from west to east coast. And they are protesting what they call anti-Indian sentiment in Congress.

Elodie Reed: In Vermont, Homer St. Francis didn’t just align the fight for Indigenous sovereignty with a nationwide movement. He also aligned his cause with that of other marginalized people around the state.

Homer St. Francis: I have calls every day from poor people and poor farmers and, and they're right up in arms.

Elodie Reed: Here he is again at that 1989 event.

Homer St. Francis: You got to stay together as a group, strength's in the numbers. So like I said, if I have to I'll start a whole new society here. I'm not afraid to adopt them into the tribe if need be.

Elodie Reed: The, quote, “tribe” St. Francis is talking about had many names, including the St. Francis/Sokoki Band of Abenakis of Vermont. We’re going to call it the St. Francis/Sokoki Band for short.

Homer St. Francis acted as the chief of the St.Francis/Sokoki Band for a total of 15 years. Not without controversy. Shortly after this group first became visible in northwestern Vermont, the anthropologist Gordon Day, as well as Swanton residents, cast doubt on St. Francis’ claims that he and hundreds of others were in fact Abenaki.

In a 1976 article in the Rutland Herald, the Swanton police chief said that he, quote, “never even knew there were any Indians in the town until about six months ago.”

Pretty soon, factions emerged within the St. Francis/Sokoki Band itself, leading to splinter groups. One of those splinter groups accused Homer St. Francis of being, among other things, quote, “power hungry.”

Jeff Benay: He was a lot of things, you know, and he was — he was a lot of things. But when Homer was on his game, and he hadn't been drinking, Homer was brilliant.

Elodie Reed: This is Jeff Benay. He is not Indigenous and has never claimed to be. But he got involved with the St. Francis/Sokoki Band in the late 1970s as the director of Indian education for the local school district. He knew Homer St. Francis well.

He says that some people saw St. Francis as a bully. But, according to Benay, that was all part of St. Francis’ strategy — to raise the profile of the St. Francis/Sokoki Band through acts of civil disobedience, and generating publicity to get into newspapers.

Jeff Benay: He made these statements, and then the major one was that … we’ll be taking over Swanton, and people would be absolutely rips***. “What do you mean, taking over like, our houses?” And you know, it was a wink and a nod, but he said, “Well, sure.” You know, and did people get upset with that? Absolutely.

Elodie Reed: In addition to the threat of taking over Swanton, St. Francis led multiple protests to fight for free fishing licenses. He also encouraged St. Francis/Sokoki Band members to stop using state license plates, and he tried to convince the federal government to leave the Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge and pay $100 million in back rent (they did not).

But St. Francis’ forceful advocacy did lead to some gains for his community. A 1986 article in Rutland Herald Vermont Sunday Magazine credits Jeff Benay’s work as the director of Indian education with reducing dropout rates in Franklin County schools.

St. Francis also founded the Abenaki Self-Help Association, which that Sunday Magazine article says it was helping people get their GEDs and distributing food to community members in need.

Something else that the St. Francis/Sokoki Band fought for was official recognition — from both the state and federal governments. They got state recognition every so briefly, in 1976, but it was quickly revoked. As for federal recognition: In 1980, St. Francis sent to the federal government a letter of intent, stating their plans to file a petition for federal acknowledgement as an Indigenous Nation.

Remember that petition, because it’s going to play an important role in this story.

North of the border, leaders of Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations were initially supportive of the St. Francis/Sokoki Band. They even issued resolutions recognizing the band in 1976 and 1977.

And there’s evidence of Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations’ support of the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki as recently as 1999.

There are numerous stories, too, about cultural exchange between Odanak First Nation and the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki — from language classes to dance groups to basketmaking. Here’s Bonita Langle, a member of one of the present-day Vermont state-recognized tribes, speaking at a press conference this spring.

Bonita Langle: I then went on to join The W'Abenaki Dancers as a teenager.

Elodie Reed: Langle is talking about participating in a group that learned traditional dances from an Odanak teacher in the late 1990s.

Bonita Langle: Where we would meet for monthly rehearsals and a potluck in Burlington, Vermont. We did many performances.

Elodie Reed: And here’s Fred Wiseman, another member of Vermont’s state-recognized tribes, speaking earlier this year to Odanak officials at a meeting of the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs.

Fred Wiseman: You can remember the old days, when I was up at Odanak a lot, teaching, helping, working with you.

Elodie Reed: Wiseman also recalls the time when these relationships began to cool off.

Fred Wiseman: But after 2003, except for occasionally, I did not feel all that welcome. I did not feel all that safe, like we had when we were all working together.

Chief Rick O’Bomsawin: My community has always been a pretty open community. And you know that.

Fred Wiseman: Maybe I overstated it. Well, not safe, but not welcome anymore.

Elodie Reed: 2003. This year being talked about here was a big pivot point. It’s when Odanak First Nation changed course — and began denouncing non-federally recognized groups claiming to be Abenaki. Like the St. Francis/Sokoki Band in Vermont.

It’s also around this time that Odanak citizens began asking people in the St. Francis/Sokoki Band who their relatives were.

That’s according to Jacques Watso, an elected official at Odanak.

Jacques Watso: When we started asking questions, “Where are you from? Which families?” That's when they raised a lot of red flags and they stopped coming to Odanak. Because they, we were trying to hold them accountable.

Elodie Reed: Essentially, Odanak officials say they realized that members of the St. Francis/Sokoki Band couldn’t produce genealogical documentation proving they were related to other Abenaki citizens — documentation that Odanak requires of its own citizens.

Also: something else happened just 10 months prior that further called into question the St. Francis/Sokoki Band’s legitimacy.

Remember the petition for federal acknowledgement that the St. Francis/Sokoki Band started filing in 1980? Well, two decades later in 2002, they still hadn’t received an official determination. Homer St. Francis, who submitted the first piece of paper for this petition, was no longer alive.

We’ll talk more in Chapter Two about why this process takes so long. But it’s at this time, in 2002, that the St. Francis/Sokoki Band did receive a response to their petition for federal acknowledgement — from the Vermont government. Specifically, the Vermont Attorney General’s Office.

This response came in the form of a 244-page document.

And just a note, we rely on a ton of public reports and documents throughout this series, so I’ve enlisted my Vermont Public colleagues to help narrate. Here’s part of what the conclusion says:

“The invisibility of any tribe from 1790 to 1974 was so complete that historians, anthropologists and census takers were unable to locate it.”

Basically, the Vermont AG’s office could not find evidence of a continuous Abenaki community in Vermont, separate from Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations. It was a public rejection of the St. Francis/Sokoki Band’s version of Abenaki history. And it wouldn’t be the last.

Josh Crane: Reporter Elodie Reed. In Chapter Two, we take a closer look at that public rejection. We also compare the processes for federal and state recognition, and why the Vermont groups failed at one, but ultimately succeeded in the other.

Vince Illuzzi: We had a general rule against having non-Vermont residents come forward.

Josh Crane: That’s coming up next in this three-part series, “Recognized.”

Chapter Two

Note: Our show is made for the ear. We recommend listening to the audio provided here. But we also provide a written version of the episode below.

To learn more about our approach to this story, you can read our editor's note, here.

Loading...

Josh Crane: From Vermont Public and the NPR Network, this is Brave Little State. I’m Josh Crane.

This is Chapter Two of our special series, “Recognized.” If you haven’t heard Chapter One yet, go back and listen to that first. We pick the story back up at the end of 2002. That’s right before the Vermont Attorney General’s Office published a report that would have major implications for the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki.

Also, a note here that this episode covers sensitive material including some slurs. Listen with care. Reporter Elodie Reed takes it from here, when we come back.

Elodie Reed: December 2002. This is 22 years into the process of the St. Francis/Sokoki Band petitioning the U.S. federal government to formally acknowledge them as an Indigenous Nation. And it’s when Vermont formally responds to that petition.

Eve Jacobs-Carnahan was the author of this response. She was a special assistant attorney general at the time. And she’s not Indigenous.

Eve Jacobs-Carnahan: Bill Griffin, the chief assistant attorney general, came to me and said, “Hey, I have a project for you.” We don’t really know anything about federal acknowledgement petitions, but you’re a good researcher, this might be fun (laughter). I don’t think any of us had any idea where it was going to lead.

Elodie Reed: In 2003, Chief Assistant Attorney General Bill Griffin told the newspaper Seven Days that more and more Vermont lawmakers were coming to him, asking about the merits of the state recognizing the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki. That’s what he said led to doing the report.

The Vermont AG published this 244-page document in December 2002. And it wasn’t focused on the merits of state recognition. Instead, Eve Jacobs-Carnahan’s research and write-up was geared specifically towards the federal acknowledgement process — like whether the St. Francis/Sokoki Band’s petition did or did not fulfill the requirements outlined by the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The report argued: It did not. Here’s a colleague, reading from the conclusion:

“The evidence raises serious questions about the existence of a tribe of Abenakis in Vermont who are a continuation of the historic Abenakis who lived at Missisquoi prior to the American Revolution. The invisibility of any tribe from 1790 to 1974 was so complete that historians, anthropologists and census takers were unable to locate it. No outside observers verify its existence during that time period.”

Elodie Reed: The AG’s office also did not find sufficient proof that Homer St. Francis and the other members of the St.Francis/Sokoki Band had Abenaki ancestry.

This caused quite a ripple around the state. Local scholars who worked with, and wrote about, the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki called the report a, quote, “hatchet job” in the press.

One open question was whether the AG’s office had a vested interest in the St. Francis/Sokoki Band failing in their bid for federal recognition.

See — recognizing an Indigenous Nation means making amends and acknowledging rights. It's not the type of thing governments are known to do readily. Bill Griffin, the chief assistant attorney general in Vermont at the time, told Seven Days that legally recognizing the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki as an Indigenous Nation would have consequences, and that it would be like, quote, “creating another state” within Vermont.

But the AG’s office also maintained that they wrote the response to the St. Francis/Sokoki Band’s petition with no other motivation apart from participating in the process.

Vermont’s not the only state to submit a response to a petition for federal acknowledgment. But it does seem pretty rare. None of the five most recent decisions on petitions for federal acknowledgement mention input from state attorneys general.

The bid for federal recognition

Elodie Reed: There are more than 1,200 federally recognized Indigenous Nations in the U.S. and Canada. Both countries have different processes in place, but broadly, what they are recognizing is that these Indigenous Nations have long and continuous relationships with their homelands. And they have inherent rights, as well as a political relationship with colonial governments. That political relationship is — or is supposed to be — government-to-government.

In other words: Indigenous Nations are self-governing, sovereign entities.

Matthew Fletcher: Sovereignty doesn't mean a whole lot if outsiders don't acknowledge it.

Elodie Reed: This is Matthew Fletcher, professor of law and American culture at the University of Michigan. He’s a citizen of the federally recognized Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. One of his areas of expertise is U.S. federal Indian law.

Matthew Fletcher: Tribes that are not federally acknowledged, they certainly can assert sovereignty over their own citizens and probably aspects of their own, of their lands. But a lot of that is kind of meaningless unless the United States government acknowledges that sovereignty, and if the United States does, then state governments have to as well.

Elodie Reed: Indigenous Nations that are federally recognized govern their own citizens — and do things like make and enforce laws and create their own taxes. They also become eligible for certain funding and programs guaranteed in exchange for the land and resources these Indigenous Nations gave up to the U.S.

Matthew Fletcher: That duty of protection, that trust responsibility, requires the United States to guarantee health, housing, law enforcement, public safety, education, all sorts of things, everything that a government does. And if you don't have federal acknowledgement, the United States government will not provide those services.

Elodie Reed: So, that’s the sort of recognition the 1,200-member St. Francis/Sokoki Band was looking for starting in the 1980s. The Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA, then assessed the application for nearly three decades.

This timeline is actually not unusual. The federal recognition process is infamously arduous.

The Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana, for instance, spent nearly 42 years in the BIA process before getting federal recognition through an act of U.S. Congress in late 2019.

And some long-standing communities, who have at times had treaties with the U.S. government, are still not recognized — like the Chinook Indian Nation in Washington, which has been seeking federal recognition for 120 years.

Matthew Fletcher: The factors that you need to fulfill the actual tests that the United States puts forward are unbelievably expensive, you have to hire expert witnesses, you have to dredge up every conceivable document, going back as far as possible for the history of the tribe.

Elodie Reed: Matthew Fletcher calls the BIA federal acknowledgment process, quote, “relentlessly bureaucratic” and “Kafkaesque.”

Matthew Fletcher: It's ridiculous, that level of unfair scrutiny that these bureaucrats put forth on these tribes.

Elodie Reed: But Dan Lewerenz says the process isn’t supposed to be easy. He’s also a professor with expertise in U.S. federal Indian law.

Dan Lewerenz: Federal acknowledgement is a very meaningful and solemn thing. It is saying that the United States government is going to have a relationship, a government-to-government relationship, with another entity.

Elodie Reed: Lewerenz is a citizen of the federally-recognized Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska and currently teaches at the University of North Dakota. Between 2015 and 2017, he actually worked for the U.S. Department of Interior, providing legal advice to the BIA office that reviews petitions for federal acknowledgement.

Dan Lewerenz: The people at Interior would say that part of their job is – part of their job is to make sure that groups who should be acknowledged are, but part of their job is to make sure that groups that shouldn't be acknowledged aren't.

Elodie Reed: When the BIA finally released its proposed finding in 2005 and its final decision in 2007, both reports said no — the St. Francis/Sokoki Band did not have enough evidence to make its case.

The BIA’s conclusions mirrored what the Vermont Attorney General’s Office had written several years earlier in the state’s response. Both essentially say: There’s just no proof that the St. Francis/Sokoki Band of Abenakis of Vermont existed prior to the 1970s. And there’s just not enough evidence that group members are descended from Abenaki ancestors.

On that last note, the BIA pointed out that less than 1% of the St. Francis/Sokoki Band’s 1,200 members could demonstrate descent from an Abenaki ancestor or, quote, “any other historical Indian tribe.” For the eight members whom the BIA could trace to an Abenaki ancestor, they did so through historical lists that Odanak First Nation has kept of its citizens.

The BIA described the St.Francis/Sokoki Band as, quote:

“A collection of individuals of claimed but mostly undemonstrated Indian ancestry with little or no social or historical connection with each other before the early 1970s.”

Therefore, the BIA determined, the band should not get the federal benefits set aside for this land’s original, Indigenous peoples.

In response to the BIA’s findings, the then-leader of the St. Francis/Sokoki Band, April Rushlow Merrill, pointed out that the group did at least satisfy three of seven BIA criteria.

Both of the legal experts I talked to, Matthew Fletcher and Dan Lewerenz, agree that it’s harder for Indigenous peoples in the eastern part of the United States than it is for those in the western U.S. to produce the required documentation for federal recognition. That’s because colonizing countries like England, France and the Netherlands didn’t have the same formalized agreements with eastern Indigenous peoples that the United States later made with western Indigenous peoples.

Fletcher says this makes the paper trail a lot harder to follow.

Matthew Fletcher: For tribes that are in the, especially in the original 13 colonies, original 13 states, they don't have that track record, the United States usually just ignored them.

Elodie Reed: But Lewerenz says there are plenty of eastern Indigenous Nations who have managed to produce enough documentation to be federally acknowledged, even if their communities had longer to contend with the violence, displacement, assimilation and family separation enacted by the settlers surrounding them.

Dan Lewerenz: So the most recent administrative acknowledgement was Pamunkey in 2016 — which is Virginia — before that was Shinnecock in New York in 2010. Before that, Mashpee in Massachusetts in 2007. And you have other northeastern tribes, Mohegan from Connecticut, the Wampanoag of Gay Head, which is now Aquinnah in Massachusetts, Narragansetts in Rhode Island.

Elodie Reed: And compared to the St. Francis/Sokoki Band’s application, which could only demonstrate that less than 1% of their membership descended from Abenaki ancestors, those eastern, acknowledged Indigenous Nations could show all or nearly all of their membership descended from a historical Indigenous community.

In the case of the St. Francis/Sokoki Band’s petition for federal acknowledgement — what stands out to me, from both the federal and Vermont governments’ responses, is that neither deny there were Abenaki peoples present in the state of Vermont between the turn of the 19th century and the 1970s. In fact, they confirm — through newspaper articles, historical journals and notes from anthropologist Gordon Day — that Abenaki peoples were visible here at various times.

Instead, what the BIA and the Vermont Attorney General’s Office claim is that they couldn’t find similar documentation showing there were distinct Abenaki peoples in Vermont, separate from Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations. At least, not from the materials submitted in the St. Francis/Sokoki Band’s petition for federal acknowledgement.

A theory takes hold

Elodie Reed: There is a theory out there about how that could have been — how there could have been a distinct Abenaki community in Vermont for so long without leaving behind a paper trail. I tried to trace this theory back. And I ended up at the research of two men.

First up: A man named John Moody. He acted as the St. Francis/Sokoki Band’s researcher for their petition for federal acknowledgement. And, by the way, I asked Moody via email whether he claims to be Abenaki. He declined to answer this question.

You’ll remember from Chapter One that, for a long time, the story was that by 1800 or so, Abenaki peoples fled Vermont and other southern parts of their territory to survive the devastation of colonization, and moved north to settle in Canada.

But John Moody theorized that some Abenaki peoples never left Vermont. Instead, he argued they avoided persecution by living in secrecy.

Moody shared his theory in a 1980 interview with the Burlington Free Press.

According to the article, Moody arrived at this theory by taping oral histories with members of the St.Francis/Sokoki Band. He said that people shared, quote, “traditional Indian skills,” like the use of herbs that, quote, “were identical to those of the Abenakis” in Odanak. Moody would not share these oral histories when I asked.

Moody also said in that article that he looked through government and church records. He concluded there were names of Abenaki peoples who were supposed to have left Vermont for the Canadian reserves by 1800, but were missing from records in Canada.

Moody’s theory that some Abenaki peoples stayed in Vermont and lived in secrecy took hold. The reports published by the Vermont Attorney General’s Office and the Bureau of Indian Affairs document how Moody influenced late-20th century historians and the books they wrote about Abenaki peoples.

The BIA, for its part, called Moody’s work, quote, “highly speculative and not reliable.”

I asked John Moody to share documentation confirming his research. He declined, and he also did not want to speak on the record.

The question now arises: Why would Abenaki peoples hide in Vermont for close to two centuries?

According to Matthew Fletcher, the University of Michigan law professor, colonization put massive pressure on Indigenous communities to assimilate.

Matthew Fletcher: The federal government effectively prohibited many tribal religions. There are a lot of people who would, you know, refuse to practice their religion because of fear of state or federal prosecution.

Elodie Reed: But in this state, there’s another explanation people have often pointed to. It has to do with something from the 1920s and ’30s called the Eugenics Survey of Vermont.

Vince Illuzzi: Folks came forward and said, “We were told by our grandparents never to acknowledge, never to admit, that we were Abenaki or had Indian heritage,” for fear of the consequences.

Don Stevens: I mean, my grandmother was on the survey. She changed her name three times because she was trying to avert the survey. And she died in the '90s. I mean, you know, it’s not that far away. So there’s still a lot of people that don’t want to be on a list, if you know what I mean.

Elodie Reed: The Eugenics Survey of Vermont was a study that lasted from 1925 to 1936. It was organized by a University of Vermont zoology professor, Henry Perkins. According to a history from UVM itself, the study aimed to reduce growth in the population of Vermont’s, quote, “social problem group.” Perkins also advocated heavily for a state sterilization law that went into effect in 1931.

Eugenics, broadly speaking, was a theory that some people are better than others, and that you should segregate or sterilize the less desirable parts of the population. It is an awful, pseudoscientific theory, and it’s something that shaped public policy in Vermont throughout the 20th century.

Mercedes de Guardiola: It would probably be easier to list the number of Vermont leaders that were against it than those who were for it.

Elodie Reed: This is Mercedes de Guardiola, a historian who just published a new book titled Vermont for the Vermonters: A History of Eugenics in the Green Mountain State. She declined to be interviewed for this story, but she spoke with Vermont Public in 2021, and that’s the tape you’re hearing.

Mercedes de Guardiola: It's so tied into policies behind social welfare, thinking behind how you provide aid to certain members of the community, how you treat people in institutions.

Elodie Reed: The Eugenics Survey lasted from the 1920s to the 1930s, but it wasn’t until 1991 that Kevin Dann wrote an article linking the survey to Abenaki peoples in Vermont.

Dann is a non-Indigenous historian, and contemporary of John Moody; Remember, he’s the researcher who said that Abenaki peoples were living in Vermont in secret to avoid persecution. We know from public documents that Dann and Moody were corresponding with one another and sharing ideas.

Ideas like John Moody saying that Abenaki peoples who remained in Vermont post-1800 were living as, quote, “gypsies.”

“Gypsy” is now seen as a pejorative term for Romani people. We’re using it here because it appears in the documents we’re citing.

And Kevin Dann appears to have taken John Moody’s claim about, quote, “gypsies” one step further. In his 1991 article, Dann wrote that among the families studied in the Eugenics Survey of Vermont for their, quote, “degeneracy,” there were the, quote, “gypsies.” And Dann said they were “primarily of Abenaki and French-Canadian ancestry.”

Dann did not cite a source for this conclusion in his article. But regardless, this narrative caught on: that Abenaki peoples were studied and targeted by the Eugenics Survey of Vermont. It was repeated and alluded to in newspaper articles, books and — more recently — in 2019 and 2021 by the University of Vermont and the Vermont Legislature, in public apologies for the impact of the eugenics survey and related state policies.

And even Vermont Public has been among the news outlets to continue repeating this narrative, on this podcast and in other stories.

Mikaela Lefrak: The Abenaki people were targets of the eugenics movement.

Mitch Wertlieb: For the original vermonters, the Abenaki, eugenics and racial prejudice led to a life lived in the shadows, where their ancestry was hidden instead of celebrated.

Brave Little State: This was a very dark chapter in Vermont’s history. It involved coerced sterilization of the Abenaki — also French Canadians, poor people, disabled people.

Elodie Reed: It turns out the truth about Abenaki peoples and the Eugenics Survey is far less certain. I called up Kevin Dann to discuss the origins of his 1991 article. And just a heads up, the audio quality isn’t great here.

Elodie Reed: Can you just tell me how you got on this path to going through the records and researching the eugenics survey?

Kevin Dann: It was the laundry building for the state hospital that had been turned into the records center.

Elodie Reed: Dann went through these cardboard boxes at the Waterbury complex that now houses a bunch of state offices.

Kevin Dann: And so it had all that atmosphere of, you know, real darkness about it.

Elodie Reed: Among the records, Dann said he recognized names of Abenaki families. But those family names weren’t from the St. Francis/Sokoki Band. They were names that Dann recognized from anthropologist Gordon Day, who studied Odanak First Nation.

But that distinction — that the names were related to Odanak — did not make it into the public presentation of Dann’s findings.

Kevin Dann: All of a sudden it became a, a, you know, Homer St. Francis standing there in front of journalists and waving some— I don't even think I published anything at that point, it might have been a manuscript thing and said, “Look, there was this Abenaki holocaust.” I mean, that blew my mind.

I felt very much that, you know, if I'd seen any evidence of anything like what they were claiming, if I, if there had been anything like that, I would have found some evidence of it. And I didn't.

Elodie Reed: What Kevin Dann told me — it calls into question the whole theory that the eugenics survey targeted a distinct community of Abenaki peoples in Vermont. It does not mean that people associated with the St.Francis/Sokoki Band and the state-recognized tribes today weren’t also impacted by eugenics. There is public documentation showing ancestors of the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki were studied in the Eugenics Survey of Vermont.

And that public documentation does refer to some of those ancestors as, quote, “Indian.”

What there doesn’t appear to be outright evidence for, however, is that these ancestors were targeted because they were Abenaki.

That’s what the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Vermont Attorney General’s Office also concluded from the materials provided as part of the St.Francis/Sokoki Band’s petition for federal acknowledgement.

And Odanak First Nation officials say this, too.

Suzie O’Bomsawin: We never said nobody from those groups went through those traumas. Maybe they went through those traumas, but not because they were Abenaki.

Elodie Reed: Suzie O’Bomsawin from Odanak First Nation says that Abenaki peoples being targeted by eugenics policies is just not something Odanak citizens ever heard about from their relatives visiting and living in Vermont.

Suzie O’Bomsawin: They never said anything related to eugenic practice. Like, not even one person.

Elodie Reed: O’Bomsawin says there are traumas that Odanak First Nation has experienced, like the traumas of residential schools. But:

Suzie O’Bomsawin: There are traumas that we didn't have. We don't need more.

We never lived in hiding. So this is not something I would like the next generation to read about. This is not what happened. Our ancestor did not hide.

Elodie Reed: So if some families of the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki were swept up in the eugenics movement, but not because they were Abenaki, then why? Why could they have been targeted?

Richard Witting: So I got aggregate data, essentially, minus the redacted names.

Elodie Reed: UVM history graduate student Richard Witting has been searching for some answers. Witting is not Indigenous. He’s been analyzing certificates issued under Vermont’s 1931 sterilization law, which he requested from the Vermont State Archives.

Elodie Reed: There are 256 known sterilization records in Vermont. And from that data, Witting says he found that sterilization was largely targeting people experiencing poverty. Also among those sterilized were young people who were institutionalized, and older, low-income women who had multiple children.

Witting says to a smaller degree, sterilization impacted immigrants, people with mental or physical disabilities, or mental illness.

He says he found no use of Vermont’s 1931 sterilization law that would suggest it was specifically targeting Abenaki or Indigenous peoples.

Witting also gained access to a handful of records with names included on them. This made it possible to explore the family histories of some of those who were sterilized.

Richard Witting: When we keep all of the information sort of wrapped up, tucked away, we're kind of ashamed of it, we won't look at it, we won’t examine the details, we won't put names to the faces, then it kind of stays amorphous. And it can be as big or small, or like, used how we want it, it becomes kind of like, I guess a myth or a story that we can, we can interpret to say something about who we are now or who we were then.

Elodie Reed: Witting's research is still unpublished, but he's already taken steps to try and correct the record. For instance, he joined Odanak citizens in the parking lot of the Ethan Allen Homestead Museum on that chilly day last spring. He considers himself an ally.

Richard Witting: I do. Yeah. As I learned about Abenaki history, I got to know the First Nations of Odanak and Wôlinak and their history and how Vermont sort of clipped them out in their story and said, has sort of marginalized them, really. This work I did, I tried to be objective. And if I did find something else, I would say some, you know, that I found something else in it. But I don't see documentation that supports the claims of the state-recognized tribes around their history around eugenics.

Elodie Reed: For now, Witting's research is more confirmation of what Odanak First Nation has said, as well as findings from the Vermont Attorney General’s Office and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Just to recap: the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki started seeking federal recognition in 1980. And there were a number of setbacks along the way — like the report from the Vermont AG’s office in 2002, and a few years later, when the Bureau of Indian Affairs officially rejected their petition. But the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki kept pushing — now shifting their focus to state recognition. And they found support from a really important group: state lawmakers.

We’ll continue down the road to state recognition after the break.

New route: The road to state recognition

Elodie Reed: After the St. Francis/Sokoki Band’s quest for federal recognition ended, the group shifted focus to state recognition. State recognition isn’t highly studied, but it’s a growing phenomenon. That’s according to a survey of state-recognized tribes published in the Santa Clara Law Review in 2008.

And it concludes that state recognition can be a, quote, “complement and supplement to the federal recognition process.” As a reminder: Scholars like Matthew Fletcher are critical of how arduous the federal recognition process is.

Matthew Fletcher: It's ridiculous, that level of unfair scrutiny that these bureaucrats put forth on these tribes.

Elodie Reed: And by the mid-2000s, state lawmakers, as well as then-Governor Jim Douglas, were growing receptive to the idea of state recognition in Vermont. With federal recognition off the table, the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki would not have rights bestowed upon Indigenous Nations, like the ability to reclaim ancestral homelands from the government.

In 2006, the Vermont Legislature passed a bill recognizing Abenaki peoples as a minority in Vermont. But this still precluded the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki from selling arts and crafts under the federal Indian Arts and Crafts Act.

To do that, Vermont would need a mechanism to specifically recognize individual groups as Native American.

This is when you see the emergence of the four organizations that you might recognize as today’s Vermont state-recognized tribes — the Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi, the Elnu Abenaki Tribe, the Koasek Traditional Band of the Koas Abenaki Nation, and the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuck Abenaki Nation. Or, as we’ll call them for short: Missisquoi, Elnu, Koasek and Nulhegan.

Missisquoi, the largest of the four, is pretty much the present-day version of the St. Francis/Sokoki Band, just under a different name. The other three are connected through family ties, or by joining forces politically in the campaign for recognition. Some folks even moved from one group to another.

Between 2007 and 2010, the four groups went back and forth with the Vermont Legislature over the process for recognizing groups as Native American tribes in Vermont. They agreed on a method that had some inherent conflicts of interest. For one, the groups applying for recognition could give input on the people who would review their applications. Among the eventual reviewers was a member of one of the groups seeking state recognition — though he didn’t review his own group’s application.

Mississquoi, Elnu, Koasek and Nulhegan also asked the Vermont Legislature that some of the federal recognition criteria not be included in the state recognition process. The Legislature obliged.

For starters, the groups didn’t want genealogy to be a requirement. Some said they feared their personal information would be exploited, citing previous eugenics policies in Vermont. And so state lawmakers allowed them to use, quote, “other methods” to trace their membership to a shared “kinship group.”

The groups also didn’t think they should be asked to document their community’s history into the distant past. And the Vermont Legislature was OK with that, only asking that groups have a “connection with” historic Native American tribes in Vermont, rather than needing to be descended from them.

Lastly, the groups specifically didn’t want Odanak First Nation citizens’ involvement in Vermont’s process. Remember that a few years prior, Odanak’s government had denounced groups like theirs.

And so the Vermont Senate added a residency requirement for those who testified during the recognition process in 2011 and 2012.

This effectively excluded most Odanak perspectives — like Odanak citizen and Albany, New York resident Denise Watso, who opposed state recognition. She said self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki groups were misrepresenting facts.

Denise Watso: Vermont put up the stockade walls, right, keeping the Abenaki people out because they had one agenda — Senator Illuzzi was to recognize these groups.

Elodie Reed: The person Watso is referring to is Vince Illuzzi. He was the chair of the state Senate committee that oversaw the state recognition process. Today, he’s the Essex County state’s attorney. Illuzzi is not Indigenous.

I asked him about this ban on non-resident testimony.

Vince Illuzzi: Although we had a general rule against having non-Vermont residents come forward, we did give them an opportunity to, to email and to write, and otherwise send us information.

Elodie Reed: And Watso, in Albany, says she did do this. Letters, emails, press releases, phone calls to lawmakers, even a couple in-person visits to Vermont.

But:

Denise Watso: We could not speak.

Vince Illuzzi: We found that the in-person meetings had been not conducive to a positive discussion, a positive resolution.

Elodie Reed: The House committee hearings don’t appear to have had a similar residency requirement at that time — but no witnesses affiliated with Odanak are listed in those hearing records. Illuzzi told me he thought lawmakers did set aside a day for out-of-state residents to testify, but records don’t show any such testimony. They show only a few people affiliated with Odanak testified during the hearings for the state recognition bills — and they were all Vermont residents.

Like Richard Bernier, who lives in Orleans County.

Richard Bernier: I live in Coventry, Vermont. I'm just a young man.

Elodie Reed: Bernier is 84 years old.

Richard Bernier: I'm an Abenaki Indian, and I belong to the Turtle Clan.

Elodie Reed: I visited him at his home on a snowy morning — he welcomed me inside and offered me his slippers, then showed me some family photos.

Richard Bernier: My mother is right there.

Elodie Reed: What was her—

Richard Bernier: But my mom was a hellraiser, OK, and anyway, and her sister brought me up. She took me when I was a year and a half old. But these are all Abenakis. All from Odanak.

Elodie Reed: Odanak?

Richard Bernier: Yeah. I've done a little research too in my time. I did a lot of it. And I know just about everyone that's Abenaki here.

I don’t wanna hurt these other people, I really don’t. They gotta live, too, OK? But why can’t they be fair with the “real” people?

Elodie Reed: By, quote, “real” people, Bernier means people who are enrolled with a federally recognized Indigenous Nation.

When Bernier traveled to the Vermont Legislature to testify against state recognition for the self-proclaimed Vermont Abenaki groups, he says he told lawmakers there was something very wrong going on — and that what went wrong could be traced back decades.

Richard Bernier: Homer St. Francis many years ago started this.

Elodie Reed: This is Bernier testifying in front of a state Senate committee in 2011.

Richard Bernier: That's not an Abenaki tribe. Far from it. Far from being an Abenaki tribe. Here's the other thing. You know, being an Abenaki or an American Indian, you're born into it. Just because they have powwows and gatherings and what have you, that don't make them Abenakis. You're born into it. You're raised in it. OK?

Elodie Reed: Also at the hearings — Jeff Benay. We introduced Benay in Chapter One. He isn’t Indigenous himself. But he has worked as the Director of Indian Education in Franklin County schools for decades. And he testified in 2011 that Abenaki students were getting taunted in school because they weren’t recognized by the state.

Jeff Benay: And all I would say: The time has come for us to put this bickering aside and let's do what is morally the right thing to do. This is a moral imperative, in 2011, we could not go another year.

Elodie Reed: I want to pause here and acknowledge that, for the most part, we are relying on archival or public meeting tape to represent the viewpoints of the groups who would go on to become Vermont’s state-recognized tribes.

The reason for that is folks from these groups have been reluctant to speak with me on the record. This has been the case ever since the spring of 2022. That’s when Vermont Public started reporting on Odanak’s denunciation of the groups here.

The Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs did provide me with the four applications that would go on to be approved for state recognition, with some names redacted. When they were submitted a little over a decade ago, the applications listed 43 people belonging to Elnu, 60 to Koasek, 260 to Nulhegan and 2,248 to Missisquoi.

As for what these applications contained: They relied heavily on stories unsupported by documentation that loosely connected their members to people publicly identified as Indigenous.

For example: The Nulhegan application for state recognition says that the ancestors of Chief Don Stevens, the Phillips family, are, quote, “believed” to be descended from a Native American “Chief Philip.” That Chief Philip is visible in public records as an Abenaki man from Odanak who signed a land deed in the late 1700s. In their application, the Nulhegan group says it considers this land deed its founding document.

We asked Don Stevens for evidence connecting him to Chief Philip. He declined to record an interview. He did respond through a public relations firm and wrote in an email, in part, quote:

“We stand by our family’s Native American history and the information submitted to the State of Vermont in the recognition process. Native cultures pass traditions, oral history, and ancestral information from generation to generation, which must be considered along with European documentation to get a complete genealogical picture.”

He goes on to reference documentation in records from the Eugenics Survey of Vermont, which identify the Phillips family as, quote, “Indian.”

The Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs approved the applications for four groups applying to become state-recognized. With the commission’s recommendations, state lawmakers voted to make that recognition official.

Peter Shumlin: And I’m honored to sign into law the official recognition of your tribes that you have fought and sought for, for so long. Congratulations.

Elodie Reed: Vermont’s new state-recognized tribes celebrated at the Statehouse.

Elodie Reed: And Nulhegan Chief Don Stevens spoke to Vermont Public about the victory.

Don Stevens: We have here affected the next seven generations of our children. I mean, they can be proud, hold their head up high. They can be eligible for scholarships in the future. We have, now, a working relationship, an official, legal working relationship with the state of Vermont.

Elodie Reed: The four state-recognized tribes would go on to get free hunting and fishing licenses, as well as certain property tax exemptions from the state. And they now qualified for certain federal benefits. Such as: the ability to label arts and crafts as “Indian produced.”

Elnu, Koasek, Missisquoi and Nulhegan are now among 60-plus entities recognized by about a dozen states as Native American. Most of them are not federally recognized.

Former Senator Vince Illuzzi calls Vermont’s state recognition process among his proudest legislative achievements.

Vince Illuzzi: I don't think these people were coming forward for state recognition for any reason other than that they were of Abenaki descent and wanted to preserve their culture.

Elodie Reed: You can hear in Illuzzi’s voice how settled state recognition might have felt back then. To many, it still feels that way now. But for Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations, it doesn’t feel settled — at all.

In fact, just this summer, they called on, quote, “relevant authorities” to investigate Vermont’s state-recognition process.

Josh Crane: Reporter Elodie Reed. In Chapter Three, we go over the ways this dispute is still unfolding today, and how it has forced some Vermonters to rethink the way they see themselves and their family.

Chawna Cota: I don't think that my family members were lying. … I believe that they thought that it was true. They were just caught up in it.

Josh Crane: That’s coming up next, in this three-part series “Recognized.” The third and final chapter of this story is available right now.

Chapter Three

Note: Our show is made for the ear. We recommend listening to the audio provided here. But we also provide a written version of the episode below.

To learn more about our approach to this story, you can read our editor's note, here.

Loading...

Josh Crane: From Vermont Public and the NPR Network, this is Brave Little State. I’m Josh Crane.

And this is Chapter Three of our special series, “Recognized.” If you haven’t heard Chapters One and Two yet, you should go back and listen to those first.

In this chapter, we’ll pick up where we left off — after Vermont created its own state recognition process and officially recognized four Vermont groups as Abenaki tribes. It was a process that all but excluded Odanak and Wôlinak, the only two federally recognized Western Abenaki Nations. And more than a decade later, they still have something to say about it.

A quick heads up that this episode covers sensitive material. Listen with care.

Reporter Elodie Reed takes it from here, when we come back.

What it means to be Indigenous

Elodie Reed: In July, Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations issued a joint press release. The two governments represent 3,000 or so citizens. And those governments said, in light of a new, peer-reviewed article, that the “relevant authorities” should investigate Vermont’s state recognition process. And then, take appropriate action.

That peer-reviewed article was published in the American Indian Culture and Research Journal by French-Canadian scholar Darryl Leroux. Leroux studied the core families in the group that preceded Vermont’s state-recognized tribes.

And through genealogical analysis, he concluded that most of those families do not have Abenaki ancestry.

Vermont’s four state-recognized tribes — Elnu, Koasek, Missisquoi and Nulhegan — responded to Leroux’s paper. Their statement said, in part, that the sources Leroux chose to use for his research were shaped by, quote, “Indigenous groups that hold a federal-level recognition status and are couched in terms of asserting control, exerting power, and eliminating competition.”

It’s a veiled but unmistakable reference to Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations. Darryl Leroux, the author, told me he started this research and got independent funding for it before he was ever in touch with anyone at these First Nations.

But it is true — that to be a citizen, Odanak and Wôlinak do require genealogical documentation.

That said, the more we reported this story out, we learned that genealogy is just one part of how Indigenous Nations determine citizenship.

Kim TallBear: This is not about individual ancestry. And when it moves from being about a people, a Nation, a collective and defending their land and place-based rights, to defending your own individual rights based on some ancestral claim, that's, that's a total problem.

Elodie Reed: Meet Kim TallBear. She’s a professor at the University of Alberta and a citizen of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate, a federally recognized tribe. And she’s the author of Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. Her name often pops up when discussing claims of belonging to an Indigenous Nation.

TallBear thinks whether or not one person has Indigenous ancestors is relevant, but not the only important consideration.

Kim TallBear: We're really dealing with living communities and proving relationships to living people. … I think if, if what you are proving connection to is only in the archive or in the grave, that's not what we do. We show connection to living communities.

If it's farther away than your grandparents, it's virtually never going to happen. You know, there have to be people that remember you, that know you, that remember your parents, that know your family, that can slot you back into the history and the dynamics and the social networks of that community.

Elodie Reed: TallBear says the role of Indigenous Nations — those living communities of citizens — is to collectively fight for the rights they’re owed by colonial entities. Remember: Indigenous Nations are supposed to have government-to-government relationships with countries like the U.S. and Canada. They are political bodies.

And TallBear thinks any state recognition process gets in the way of that. Vermont’s process, for instance, requires state-recognized groups to sign away their rights to land claims.

Kim TallBear: I don't think states should be in the business of recognition. Our historical agreements, and treaties are not with states, states are direct competitors to tribes and tribal sovereignty.

Elodie Reed: Part of what tribal sovereignty means is that Indigenous Nations get to set their own criteria for who can belong as a citizen. And TallBear stresses that belonging is not something an individual can claim without input from that Indigenous Nation.

Kim TallBear: Because it is absolutely not a private matter. And that is something I think is hard for settler institutions to understand because they're thinking in terms of gender and ethnicity.