Heads up: This story contains sexually explicit content and language.

Brave Little State is Vermont Public’s listener-powered journalism show. Each episode begins with a question submitted by our audience. Today, we focus on this listener question:

“Why did the girlie shows close down at the county fairs? Why are there no strip clubs in Vermont? Signed, a stripper who grew up in Vermont.”

Reporter Sabine Poux takes on this question, and discovers a surprising — and convoluted — history involving ‘girlie shows’ at county fairs, strip clubs around the state, and not-so-subtle political battles to rid Vermont of adult entertainment establishments once and for all.

Note: Our show is made for the ear. We highly recommend listening to the audio. We’ve also provided a transcript. Transcripts are generated using a combination of robots and human transcribers, and they may contain errors.

Loading...

Girls, girls, girls

Sabine Poux: From Vermont Public, this is Brave Little State. I’m Sabine Poux — at the Tunbridge World’s Fair.

Sabine Poux: Hi, sorry, hi, my name is Sabine. I'm a reporter with Vermont Public. I'm doing a story, a historical story, about the about the girlie shows that they used to have here—

Martha Howe: (laughter) Oh, God! He’ll tell ya.

Gary Howe: I never got into one.

Sabine Poux: Why not?

Gary Howe: Because I was too young.

Sabine Poux: How old did you have to be?

Gary Howe: I don’t know. We used to sneak in. Try to get in under the tent, but they always caught us. That was a long time ago though.

Martha Howe: He and his brother. He’s not talking about me. He and his brother!

Sabine Poux: Did you go to the shows, do you remember them?

Baxter Doty: Once.

Sabine Poux: Once?

Baxter Doty: Yep.

Sabine Poux: Can you give me some memories?

Baxter Doty: Oh— (lots of uncomfortable laughing)

Eliott Morse: Ooh, the girlie shows.

Sabine Poux: Do you remember the girlie shows?

Eliott Morse: Yeah. They called this a “drunkards’ reunion,” the fair.

Sabine Poux: “Drunkards’ reunion”?

Eliott Morse: Drunkyards’ reunion, yeah. And the girlie shows were right down at the very other end of the fair, where you go in. And my folks said, when I was, you know, probably 15, 16 they said, “You can go to the fair, but don't go near the girlie shows.”

Sabine Poux: I’m on Antique Hill, between booths of maple syrup makers and chair weavers, dressed in old-timey costumes. It’s all very historical here. People at the fair — they LOVE fair history. But there’s this one piece of history that no one is really talking about — the girlie shows.

Louise Mier: In the same breath that anybody said, “Going to Tunbridge fair,” somebody would say, “Oh, at night?”

Sabine Poux: Implying—

Louise Mier: Implying that—

Frank Mier: They were, they were in the afternoon too.

Louise Mier: Yeah, but it's certainly implying that they might take in the girlie shows.

Sabine Poux: The girlie shows were basically strip shows, or burlesque shows, that would travel from fair to fair every summer, landing in towns like Tunbridge. They lasted up until the 1970s. And there’s nothing about the girlie shows on display here. No photos on the walls of Heritage Hall. No real sign they ever existed.

Still – when I ask people at the fair about them, it’s clear they left quite the impression.

Sabine Poux: What did you hear about the girlie shows from people you grew up with?

Eliott Morse: They were disgusting, they said, people that went. "They were disgusting.” They said bad things about ladies. Ladies don’t deserve that.

Betsy Race: I knew — All I knew was that we weren't allowed to the fair. As a kid, we weren't allowed to the fair, except on Sundays. That was my family's rule. Saturday night was too wild. You didn't take your kids. Now my parents came, but no kids.

Sabine Poux: Do you think they went to the girlie shows?

Betsy Race: Not my mother. Nah.

Sabine Poux: You had to be 18 to get in, and there were no women allowed. Though, it wasn’t very hard to skirt the rules. The shows made a lot of money for the fairs. And just about everyone was getting a piece of the pie. The Orange County Sheriff’s Department? They ran one of the tents, according to local lore.

Still, a lot of people snuck in.

Sabine Poux: So, you get under the tent and—

Baxter Doty: You just watch ‘em. Just watch ‘em do their thing.

Sabine Poux: Do you know anything about the girls who would perform in the shows? Or did you ever meet any of them?

Eliott Morse: No. I think they came from away. I think they got them in here from other places.

Betsy Race: My recollection is that most of them were probably not from anywhere in Vermont, for sure.

Sabine Poux: Were they sort of separated from the rest of the fair?

Betsy Race: No. (Laughter) No, this one was happened to be right next to Floral Hall. (laughter)

Sabine Poux: This is your husband?

Betsy Race: Yeah. Let’s see. … Hey—

David Race: Hi.

Betsy Race: Hi. David, wait a minute.

David Race: What?

Besty Race: Did you ever go to a girlie show here at the fair?

David Race: Why?

Betsy Race: Well, she kind of likes to know what it was like when the girlie shows were here. And I told her I went the last year. Remember, Jim and I snuck in? I told you about? Did you ever go?

David Race: Yeah.

Betsy Race: How old were you when you first went?

David Race: Well I’m not incriminating myself.

Betsy Race: Were you more than 14?

David Race: Yeah.

Betsy Race: 15?

David Race: You had to be 18 to get in there.

Besty Race: And you weren’t?

David Race: I wasn’t 18. Snuck in.

Sabine Poux: How’d you sneak in?

David Race: Go under the tent, or around through the exit. If nobody was watching it.

Dave Smith: Well, I’ll tell you a story. It's a true story. That the minister at the church, OK, was preaching – it was a lady, new minister — she was preaching that we have to get rid of the girlie shows at the fair. OK? So the following week, the board of deacons met, and they fired the minister. (laughter) True, true story.

Sabine Poux: That minister may have lost the battle, but she won the war. There are no more girlie shows at the Tunbridge World’s Fair. The only dancing these days comes from the famous Ed Larkin Dancers, who contra dance in elaborate period costumes.

I didn’t know about the girlie shows before. The person who first brought them to my attention — she grew up near the Tunbridge World’s Fair long after the girlie shows had already gone away. These days, she works as a stripper out of state. And, she’d prefer we don’t use her full name or her voice in this story

She has never really felt like she could talk about her profession, openly, in Vermont. She also can’t work here since there are no strip clubs here anymore. Vermont is actually the only state in New England without any.

But then she found out about the girlie shows — and the fact that they were so close to where she grew up — she got excited.

She wanted to know more. So she asked us: “Why did the girlie shows close down at the county fairs? Why are there no strip clubs in Vermont? Signed, a stripper who grew up in Vermont.”

Brave Little State is a proud member of the NPR Network. Welcome.

_

‘Carnival Strippers’

Shortie: You have to play with them. You do. You have to play with them. You have to tease them. Make them think they're a man, even if you don't think they're any more than a dog. Make them think, you know.

Sabine Poux: This is an old interview with a girlie show performer who goes by Shortie. And here’s another dancer, who goes by Debbie.

Debbie: You know, it's just a job. It's in your system, you know, once you work for the fairs, it's in your system. Because, last year, I swore I never come back, and I'm back here. I don't know why, but I'm back.

Sabine Poux: In the early 1970s, a photographer named Susan Meiselas, fresh out of college, decided to follow the girlie shows around New England and document them, from Maine to Vermont — in Tunbridge and Barton and Essex Junction. Susan spoke with strippers and staff and members of the audience. She got up close in a way a lot of women couldn’t, since only men were allowed into the tents to watch.

Susan Meiselas: Being excluded is part of what motivated me. It's like the idea that I was a woman, I couldn't see what women were doing with these men was a big, you know, propelled me to try and sneak in.

Sabine Poux: She compiled her interviews and photographs into a 1976 book called Carnival Strippers — and into recordings like the one you’re hearing now.

Barker: Now, look, this is a strip tease show, it’s a burlesque show. This show has been set aside for the Minutemen only, no ladies and no babies. You must be 18 years of age or over to see this show, because if you’re under 18 you wouldn't understand it. If you was over 80, Lord knows, you waited too long, and your eyes couldn't stand it. Stallion, step out. Candy. Step out. Stormy, the body is here. Now look, fellas—

Sabine Poux: While the fairgoers I talked to shied away from offering the lurid details, the interviews Susan got are really honest. The performers talked about what it was like to let audience members touch them. How at times, they felt really strong, empowered; at others, utterly disgusted and upset; and how the community of dancers they found backstage could be a sort of antidote to the loneliness and isolation that could come with the job.

Susan spoke with one stripper named Lena, who started dancing in the girlie shows when she was 18. She hoped it would help her get her back on her feet after divorce, and give her an opportunity to see the world. She had dreams of eventually dancing on TV.

Lena: I like attention, but I think, I think what I like more about stripping is, is that it's sort of something that's not socially accepted. You sort of have to live in a man's world. I think as far as being a stripper, it's close to being in a man's world as you can be. I mean, like the way women look at it as sort of thing revolutionary, I mean, and sort of being able, for the first time in their lives to say, I've got you eating out of the palm of my hand. Because, I mean, that's essentially what the men are doing when you're performing.

Sabine Poux: The tape of these performers from the 1970s… they’re some of our only first-hand accounts from the girlie show era. A lot of the dancers, including Lena, have since passed away. And the girlie shows themselves are long gone.

A more family-friendly fair

Susan Meiselas: I began to hear that in ’78 and the 80s, specifically in Vermont, the shows were closing. And there were lots of, there were, people had different ideas about why.

Sabine Poux: This is a present-day interview with Susan, the photographer who documented the girlie shows in the 70s.

Susan Meiselas: You know that the porno market and video market was starting you know, the sex industry was sort of focused on pornography more than it was these kinds of events. And there were places opening up in small towns, you know, peep shows and things like that, that weren't there before. So sex was more available, let's say, than waiting for the country fair to come to town once a year.

Sabine Poux: This idea — that a new kind of sex industry was moving into the mainstream and replacing the girlie shows — I heard that from a lot of people. One Vermonter remembered how, starting in the 1970s, you could watch a pornographic movie at the Midway Drive-In in Ascutney. In the movie theater and in their home living rooms, people could indulge in their fantasies in private.

Susan Meiselas: You know, it was different experience. You weren't as, as exposed to the live, let's say. You know, live — people saw you, you know, interacting so that you other people witnessed how you performed as a man in that setting, whereas video — it doesn't implicate them in the same way.

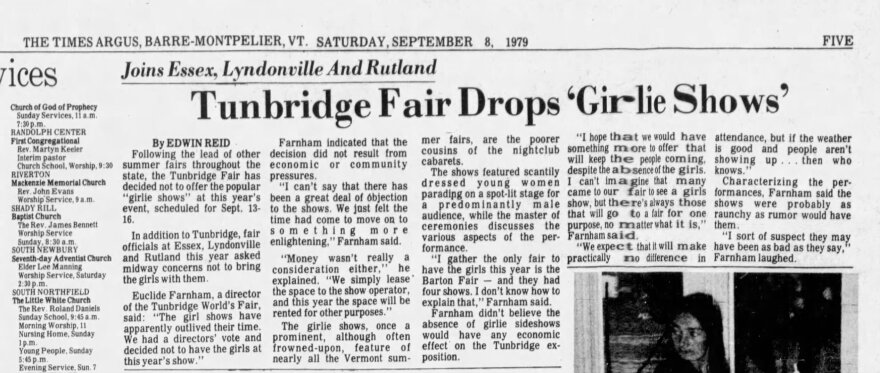

Sabine Poux: Those softer cultural pressures seemed to overlap with harder pressures, from officials. The state fair in Rutland got rid of its popular girlie shows for a short time after an alderman and reverend quote, “paid the shows a visit.” A few years later, in 1979, that fair would close its girlie shows for good. The president of the state fair association was quoted saying that the shows were a thing of the past, and that you could “almost see on the street what you see in the shows”. At least two other towns ended their girlie shows that summer, too.

In Tunbridge, Fair Director Euclid Farnham told a reporter the time had come to quote, “move onto something more enlightening.” Here’s Euclid speaking about that decision in a 2015 video from a local business.

Euclid Farnham: I’m convinced we would’ve lost the fair if we had not changed.

Sabine Poux: In 1979, the fair’s board of directors voted to leave the girlie shows behind completely.

Gary Young: When I turned 18, that was it. No more. That was the last year they had ‘em.

Sabine Poux: Were people excited to have them gone? Were people bummed? What was the reaction?

Betsy Race: Are you kidding? The men were all, “What? No girlie shows this year? What the heck are we going to do?” I think men were more disappointed than anybody else.

Gary Howe: And now they've got rid of the demolition derby. That made a lot of people mad, because they like to see people smashing up stuff. It kind of turned into a family-oriented kind of fair, really.

Eliott Morse: This town is not about the girlie show. It's, it's not being a drunkard’s reunion. That's maybe there's a few drunks in town. There is in every town, but most people are pretty straightforward in this town, and they love history. They just love history.

Sabine Poux: Do people talk about the history of the fairs from the girlie show era?

Eliott Morse: I hardly ever hear that talked about. I think they're glad that's over with.

Fighting Fantasy

Sabine Poux: While stripping was moving out of Vermont’s fairgrounds, it was springing up in other places: local bars and strip clubs. In the 80s and early 90s you could find nude dancing around the state, according to newspaper articles at the time. There was Shooters in Barre. Hollywood’s Hardbodies and the White River Amusement Pub — or, the WRAP — in White River Junction. Uncle Sam's in Rutland.

For a while, there were also plans to open a club on one of the main drags in South Burlington.

But people in South Burlington? They didn’t like that.

Will Cimonetti: I bring this meeting to order, please. We’ll open this meeting as we do all city council meetings — with the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag.

Sabine Poux: It’s 1995 in a middle school cafeteria in South Burlington. A row of men wearing ties and dress pants stand in front of a curtained stage.

Councilmembers: I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America. And to the Republic, for which it stands…

Sabine Poux: After the pledge, they sit. A woman brings over two cups of coffee.

William Cimonetti, council chair — he takes the mic.

William Cimonetti: At this point in time, I declare open the public hearing on the public indecency ordinance.

Sabine Poux: This “public indecency ordinance” — it’s come up in response to a plan to open a strip club in town, called Club Fantasy, on Williston Road. William, the council member, he doesn’t want to mention Club Fantasy straight-up in his presentation. So, he says this:

William Cimonetti: It is the purpose of this ordinance to regulate public indecency, including public nudity, which is deemed to be a public nuisance. Section three, definitions. “Nudity” shall mean the showing of the human female—

Sabine Poux: And we get one of my favorite euphemisms of all time:

William Cimonetti: —or the depiction of covered male genitals in a discernibly turgid state.

Sabine Poux: Anyway. The meeting is packed with hundreds of South Burlington residents. Many do not want Club Fantasy to open in their town.

Andrea Leo: I grew up in Vermont for 25 years. And I think this is a disgrace to Vermont, and to the city of South Burlington. First of all, Vermont is known for its wholesomeness, I think. And people come here to see our state for its niceness. Not for dancing naked at Club Fantasy.

Mark Faye: I’m asking you to hold firm in your ordinance and assure you, if you do, you will have God’s blessing. I believe if you take a stand for what is right, Mr. Cliche and his lawyers will not be fighting against the city, but the almighty himself. Thank you. (Clapping)

Sabine Poux: There is a lot of this, shall we say, discernibly turgid testimony. And that Mr. Cliche the one resident mentioned, that’s Shawn Cliche. Club Fantasy is his idea.

Shawn Cliche: We plan on putting on all types of dancing, whether it be dancing for patrons...

Sabine Poux: At the time, Shawn's young — just 28 years old — and he’s a stripper himself, who sometimes works bachelor parties and work events. He has the haircut of a 1990s football player. And he looks agitated as he fields councilmembers’ questions about the club.

William Cimonetti: So, it is a matter of record, then, that it is your intention then, if granted this permit, that included in dancing would be nude dancing?

Shawn Cliche: Yes.

Sabine Poux: The council approves the indecency ordinance, which effectively bans nudity inside public South Burlington businesses. So, later that night, when Shawn’s applications go before the council—

William Cimonetti: And the application is denied. (Clapping)

Sabine Poux: — his fate’s pretty much sealed.

So, full nudity is off the table. But ultimately, South Burlington does begrudgingly allow the club to open, as long as dancers cover up — at a minimum, in pasties and g-strings.

But here’s another twist: The partial victory is short lived.

(phone ringing)

Shawn Cliche: Hello, Shawn speaking.

Sabine Poux: Hi Shawn, this is Sabine Poux, I’m a reporter with Vermont Public.

Sabine Poux: This is the Shawn Cliche. Of Club Fantasy infamy. By the way: Shawn’s last name is spelled “cliche,” even though it’s not pronounced that way. Missed opportunity.

Sabine Poux: I’m putting together a story for the podcast we do about why there are no strip clubs in Vermont,and I’ve been going down some rabbit holes.

Shawn Cliche: (Laughter) I guess you’ve been going down a few rabbit holes, huh?

Sabine Poux: I sure have. I sure have. Um—

Sabine Poux: Shawn’s almost 60 now, and splits his time between Florida and New York. He says he no longer likes the culture or the politics of Vermont — the culture and politics that kept his business in flux for two years.

Shawn Cliche: We were open and closed several times. I'm going to say probably about a total of six months of being open.

Sabine Poux: The city kept nabbing the club for violating its rules. Shawn sued them for denying his licenses. And at one point, the club even offered a drink special called the “City Council Shuffle” — vodka and orange juice, also known as a screwdriver. It got so dramatic that a local playwright even wrote a play about it all, called “The Taboo of Fantasy.”

But even when the Vermont Supreme Court ruled partially in Shawn’s favor, it was too late. Shawn was out of cash.

Shawn Cliche: And basically I was, we were out of business due to a lack of funds.

Sabine Poux: When the club closed, Shawn says the Club Fantasy dancers moved out of state to find work elsewhere.

Other city councils saw what happened in South Burlington and quickly passed anti-indecency ordinances of their own — like in Richmond, Essex, Shelburne, Vergennes and Williston. The shadow of Club Fantasy loomed large. Even Vermont’s only Hooters location lost its liquor license in 2008 for holding a bikini contest that quote, “got a little crazy.” And it, too, would eventually close.

Shawn Cliche: I can tell you, there are a lot of laws on the books that were enacted because of me.

Sabine Poux: Effectively, the door was closed on new strip joints in Vermont.

But strippers and sex workers — they’re still here.

Henri Bynx: Like, putting this organization together with everybody has, like— impacted the survivability, you know, of like living in this state.

Sabine Poux: That’s when we come back.

(Sponsor break)

Last club standing

Sabine Poux: After the Club Fantasy saga in the late 1990s, a bunch of Vermont towns passed laws that essentially, legally, barred strip clubs from opening in Vermont.

Planet Rock, in Barre, was the last holdout. It’s the club most people will mention these days when Vermont strip clubs come up in conversation.

And the story of Planet Rock is linked to the story of Club Fantasy. One Burlington Free Press reporter speculated that Planet Rock was able to avoid scrutiny when it opened in the ’90s because the other club was taking up so much oxygen in the public eye.

Still, Planet Rock was plagued with its own troubles. In 1998, city councilors in Barre ruled that dancers had to stay an arms-length away from patrons.

Henri Bynx: And even in that club too, lap dances were four feet away with your top on.

Sabine Poux: Sexy. (laughter)

Henri Bynx: Yeah, super duper, like.

Sabine Poux: Henri Bynx, of Montpelier, used to work at Planet Rock, as a dancer. They came to Vermont in the mid 2010s to farm. And they worked at the club in the last year and a half before it closed.

They remember Planet Rock as a true dive — with a sun-bleached cardboard cutout of a woman standing in front.

Henri Bynx: What I remember from that time — we had the same four dancers on rotation. The clientele is, like, very working class and friendly, and actually oftentimes, like, still some of my favorite today, like farmers would come in and we'd like talk shop, you know, (laughter) like, never happens in other clubs. You know what I mean? Very cute…

Sabine Poux: Henri says it felt like the club had its heyday in the 1990s. And, ultimately, it struggled with a lot of the same issues that others did, like tightening regulations and an aging clientele.

Henri Bynx: I feel like everyone was just kind of there, keeping the thing alive for a few, until they figured something out. You know, it was kind of sad.

Sabine Poux: In the 2010s, Planet Rock did close, for good. Henri turned to other jobs, like farming, and started traveling around to find stripping and sex work elsewhere.

It’s clear from old newspaper articles and records from old meetings why Vermonters blocked strip clubs from opening in their communities: morality, family values, the perceived danger that opening up a club might bring. These are the same things that came up when fair officials closed down the girlie shows a few decades before.

But here’s the thing: other New England states do have clubs. Vermont is the only New England state without one. Just last fall, a gentleman’s club called “Suga’z” opened up in Colebrook, New Hampshire, right on the border with Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom.

So — why, then, is Vermont this outlier?

Sabine Poux: I'm curious, like, why you think, what you think it is about Vermont where we've decided culturally, like, this isn't something we're gonna have, and people are gonna try to shut them down every chance they get?

Henri Bynx: Um, I guess— Well, have you read anything about, like, the history around the kind of tourism Vermont's tried to attract, and, like, the absence of billboards and why that was—

Sabine Poux: Henri is referencing the laws that Vermont has put in place to keep the state looking and feeling a certain way, like Vermont’s 1968 law banning billboards. These are laws, in part, about the image Vermont projects to the world. An image, as one testifier in South Burlington put it, of “wholesomeness” and “niceness.”

Henri Bynx: The same ethos that said, “Billboards will attract poor and marginalized tourists, and we don't want that riff raff in our neighborhood,” is the same in ethos that says, where there are billboards, there's strip clubs, and where there’s strip clubs, “there's riff raff.”

![Henri Bynx (left), used to work at Planet Rock in Barre as a dancer. They're one of the founders of the Ishtar Collective, a group that advocates for the rights of sex workers in Vermont. Here Henri stands next to [TKTK].](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/4d9b888/2147483647/strip/true/crop/4032x3024+0+0/resize/880x660!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnpr-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Ff1%2Fa6%2F69725578450da5e68fb823ea9d74%2Fimg-5624.JPG)

‘Securing community’

Sabine Poux: A few years ago, Henri co-created a nonprofit called the Ishtar Collective. The group advocates for the rights of sex workers in Vermont.

Because, while it’s true that there are no more girlie shows at the fairs, and stripping has all but disappeared from Vermont, strippers and sex workers, more broadly — they’re still here. There are people who create content online, who travel around and strip out of state, and even people who do sex work in-state, even though it’s still criminalized here in Vermont.

One of the focuses of Ishtar is just to talk more openly about sex work. And they’re creating the kind of community that people like Henri haven’t always been able to find in Vermont.

Henri Bynx: I had a hard time when I was, like, traveling and doing sex work. I had a hard time like, securing community. So, like, putting this organization together with everybody has, like, given me an essence of that. And it's been, like, honestly, like, really — it's, it's impacted the survivability, you know, of like, living in this state. I think that it would have been a lot harder.

Sabine Poux: Today’s question-asker — the one who signed her question “a stripper who grew up in Vermont” — she doesn’t want to be identified in this story. However, there are a couple things she wants to put out there.

First, she says she wishes she knew more about the women who performed in the girlie shows at Vermont fairs: What were their bonds like with each other? Did they feel welcome in Vermont? Did any of them live locally? With so much of their stories hidden behind scandals and sensation, she wishes she could understand more about who they were as people.

And, she just wants them to know how grateful she is for them. She says she’s so proud to be connected to them — to this lineage of strippers in Vermont.

And one more thing: If our question-asker were ever to work as a stripper in Vermont, she’s already got a stage name picked out: “Sugarbush.”

_

Loading...

Credits

This episode was reported by Sabine Poux. It was produced and edited by Josh Crane and Burgess Brown. Additional support from Sophie Stephens. Angela Evancie is Brave Little State’s Executive Producer. Our theme music is by Ty Gibbons; other music by Blue Dot Sessions.

Special thanks to Susan Meiselas and Magnum Photos for the materials from Carnival Strippers and Carnival Strippers Revisted.

Additional thanks to Liam Elder-Connors, Jeff Haig, Steve Taylor, Scott Rogers, Fern Strong, Elaine Howe, Gail Weise, Jordan Mitchell, Matt Sutkoski, Lydia Flanagan and The Mutual Admiration Society, as well as everyone we spoke to at the Tunbridge World’s Fair: Gary and Martha Howe, Baxter Doty, Dave Smith, Louise and Frank Mier, Elliot Morse, Betsy and David Race and Gary Young

As always, our journalism is better when you’re a part of it:

- Ask a question about Vermont

- Sign up for the BLS newsletter

- Say hi onInstagram and Reddit @bravestatevt

- Drop us an email: hello@bravelittlestate.org

- Make a gift to support people-powered journalism

- Tell your friends about the show!

Brave Little State is a production of Vermont Public and a proud member of the NPR Network.