Brave Little State is Vermont Public's show that answers questions about Vermont that have been asked and voted on by you, our audience — because we think our journalism is better when you're a part of it.

Note: Our show is produced for the ear. We recommend listening to the audio on this page. A written version is below.

Subscribe to Brave Little State for free, so you never miss an episode:

Loading...

Today's winning question occurred to Khrista Trerotola when she was listening to our recent episode about downtown revitalization in White River Junction.

"And one of the [restaurant owners] interviewed in it was talking about how they're short-staffed," Khrista says. "And it just dawned on me that we're hearing so much about restaurants being understaffed, short-staffed, unable to open because of their staffing status."

"It's about me genuinely understanding, when everyone says, 'I can't hire people,' like, where have they gone?"

Vermont’s restaurant workforce has shrunk by more than 12% — about 2,600 people — since a few months before COVID. That's based on data from the Vermont Department of Labor comparing employment statistics from October 2019 to October 2022. For comparison, that’s more than twice the percentage of people who are out of the retail game over the same time-frame.

To better understand the data, we decided to focus on the story of one restaurant, from the very beginning to the end of an era, and get a sense for what the ex-staffers of that restaurant are up to now.

A Colchester greasy spoon

The Guilty Plate Diner opened its doors in 2013 at the site of a former Video World.

"It was good food fast!" says Michael Alvanos, a former co-owner. "You're not going in for, you know, white table service."

You know the drill: eggs and pancakes in the morning, soups and sandwiches at lunch, red booths, counter seating, black and white checkered floor, soda fountain.

Michael said he wanted The Guilty Plate to serve as a contrast to the trendy farm-to-table restaurants that had been popping up all over the area. Hence, the name “Guilty Plate” and also the welcoming family vibe.

"You know, you come in. 'Hi, how you doing? Coffee?' 'Yes,' you know, and they would know your order," Michael says.

A family affair

The emphasis on family wasn’t just for customers. Michael’s fellow co-owner was his older brother, Evan. Michael and Evan's parents, George and Christine, were both involved too. The Alvanos family operated restaurants in the area for years, including the Pine Street Deli in Burlington’s South End.

That’s where Michael met Taylor Courville, a fresh-faced 16-year-old at the time, and Nick, or “Niko,” Sobolev.

"I had just gotten out of the army and off of deployment and was working at Price Chopper," Niko says, "And all of my roommates at the time had slowly started getting jobs at the Pine Street Deli. And then the rest is history."

I interview Michael, Taylor and Niko together at Michael's house to walk through their shared history. When the conversation turns to the origins of The Guilty Plate in 2013, Michael gestures across the table. "I was able to finagle these two into tagging along," he says, "And they both were young enough and, quite frankly, naive enough to come along with me."

Michael says “naive” because, in some ways, the Guilty Plate Diner was like a grand experiment: a chance for the Alvanos family to transition from a deli to a full-time restaurant, and an opportunity for Michael to combine his restaurant career with his architecture career. He’d been working both jobs simultaneously.

"I never wanted to step out of architecture," Michael says. When I ask if he felt pressure from his family to stay in the restaurant biz at the time, Michael laughs. "Big time, big time. There's a massive, you know, tension. I think it probably resulted in the end of my first marriage."

When the property that would eventually become The Guilty Plate came on the market, Michael saw an opportunity to put his architecture skills to good use. One of the first steps was to figure out the restaurant layout.

At this point in our interview, Taylor interjects.

"Should we talk about the hallway?"

The hallway. When the guys were first setting up the diner, they realized that the hallway to the kitchen was too narrow to fit some of the cooking equipment. "So our equipment had to go through our serving window with, like, three dudes on each side, like, manhandling this massive oven, to fit it through," Taylor says.

"But to my credit, I gave you guys a huge [serving] window to be able to put the equipment through," Michael says, "So, I think, mission accomplished."

Everyone laughs.

_

By the time The Guilty Plate was up-and-running, Taylor and Niko were basically honorary members of the Alvanos family. Though, while everyone in the kitchen shared responsibilities, Taylor and Niko recognized one true leader: Michael’s older brother, Evan.

"Ferocious leader," Taylor says. "He was the glue."

"Evan was the chef," Niko says. "I know we all joke around and call each other 'chef,' but Evan was The Chef."

Michael describes Evan as laid back in the kitchen, confident in his ability to put out any proverbial (or literal) fires. Though, he says it was their relationship with each other that made the kitchen a success, more than any one individual.

"Our timing was impeccable because we've worked so long together," Michael says.

The guys would talk about all sorts of things while cooking, though Niko always wanted to talk about one thing, in particular: the universe. And not in an existential way.

"We would talk about black holes, and just all the crazy science stuff you'd see in the news," Niko says. "We definitely had a full board of tickets and we’d be like, "Oh man, Schwarzschild radius..."

"And if your listeners know, you know, I don't believe in the Hawking Radiation Theory," Michael says. "I think Stephen Hawking was wrong."

This is getting weird.

"Listen, we’ve spent far too much time together," Michael says.

Enter Angie Pierce, a former server at the Guilty Plate.

“Yeah they definitely had a crazy bond that was just so awesome to witness," she says.

I wanted Angie’s perspective on working at the diner because, at least at first, she was a bit of an outsider. She was hired in 2016, a few years after the diner had opened. And she came with about a decade of experience working in other Vermont restaurants, which means she would know if working at the diner really was as special as Michael, Niko and Taylor made it out to be.

“It was definitely that family feeling,” Angie says. “You know, it's just that, like, this is my family.”

“For me, as a waitress, you know, sometimes you're in situations that are not necessarily ideal, you know, people can get pretty unruly in a sense," she says. "And I never, I never felt like they didn't have my back in any situation."

A restaurant exodus

The tight bonds among the former staff of the Guilty Plate may make it a little surprising that very few of them are still working in the restaurant industry at all. Michael, Niko, Taylor and Angie are all currently pursuing totally different careers.

It also might be surprising that, prior to COVID, none of them had seriously considered leaving, even though the work was really hard.

“We would have days where from 7 a.m. until, like, 2 a.m., not one of us would have gone to the bathroom once," Niko says, "And then we were just kind of like — whatever. That's the job.”

"Especially as a single mom, it was more than just a job for me. I would be walking away from my biggest support that I had in Vermont," Angie says.

"At the end of a Sunday breakfast rush it was like, I can't do this anymore," Taylor says. "But, you know, you'd go to work the next day. And, you know, you'd be around the people that you loved, and you just kind of kept pushing along.”

What happened at the Guilty Plate is an example of the transformation that a lot of places — and people — went through because of COVID.

When I posed Khrista’s winning question to social media, a ton of you shared your stories about leaving the restaurant industry. One trend seems to be that few with experience working in restaurants are surprised by the current restaurant worker shortage.

I also posed Khrista's question to economist Mathew Barewicz from the Vermont Department of Labor.

“The data points to, like, an increase in acceleration of retirements during the pandemic,” he says.

The data he’s referring to shows that Vermont has one of the oldest workforces of any state in the country. It’s been an ongoing concern for our Governor, Phil Scott.

“It’s just a math issue," Gov. Scott said during a press briefing on Oct. 25, 2022. "You’re going to have a labor force problem eventually."

"The pandemic exacerbated that, but it was going to happen anyhow.”

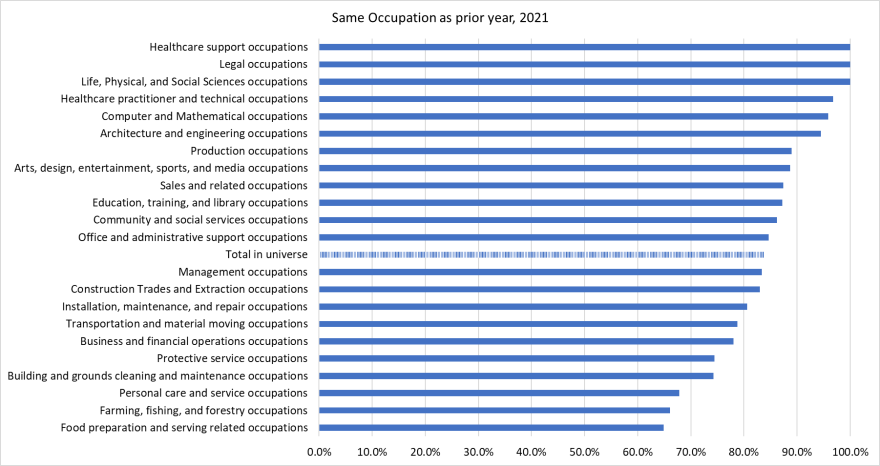

Matthew Barewicz also points out that, even before the pandemic, food prep and food service jobs had the highest turnover rate of any job category.

“You're basically saying one third of everybody who's currently working in a restaurant or bar is probably not going to be there a year from now,” he says.

Basically, the restaurant industry was already operating close to a knife’s edge. Even a little disruption would make a big difference. The pandemic was more than a little disruption.

The end of an era at The Guilty Plate

All the data in the world still wouldn’t encapsulate what happened at The Guilty Plate Diner in 2020.

“There was just too many, too much had changed in such a short amount of time,” Michael says.

The diner shut down for the first time in March 2020, after Gov. Scott's moratorium on eating inside.

“[I] couldn’t believe it. It was like a bad dream,” Taylor says.

What started as a bad dream quickly turned into a nightmare.

Evan Alvanos, Michael’s older brother and fellow co-owner of the diner, died on April 10th, 2020. He was one of the early Vermonters to die from COVID.

“Evan simply had an unfailing work ethic, and would not give up,” his obituary said. It also included Evan’s own description of the The Guilty Plate Diner staff: “a true dysfunctional family who I respect and love.”

Michael told me that because of COVID restrictions, they Evan's family was not able to hold a formal funeral. He also said Evan’s death served as motivation for the diner staff to reopen.

“After [Evan] passed away, I did ask these guys. I said, ‘Hey, listen, let's let's try to do this again.’”

"Motivation was there to reopen it for [Evan]," Taylor says. "Yeah. To bring us all back together.”

The diner reopened at reduced capacity in June 2020. But normalcy was hard to come by.

“It was like, this is for Evan. We're gonna make this exactly the way it was,” Niko says. “And it was just an impossible task because he wasn't there.”

“[He] was Mike's actual big brother and he was like a brother to us,” Taylor says. “And it was hard to be there. It was very difficult to be there. And, you know, lik,e it got to a point where you just didn't see yourself wanting to be there.

“Beyond just losing a boss, it was losing the heart of the diner,” Angie says. “I mean, Evan brought so much to the diner besides just food.”

I think one of the answers to Khrista’s question — What happened to all the restaurant workers? — is the same as the answer to what happened to the rest of us. No one survived those early months of the pandemic unscathed. And too many didn’t survive.

Meanwhile, restaurant workers were dealing with all of that at the same time as they were trying to do a hard job that had become much harder, basically overnight.

“You know, we were still inside a building with hundreds of strangers coming through in the day," Niko says. "And so it was honestly a little nerve wracking on us on top of everything else that was going on, to have that additional element of exposure.”

“Just from my own personal observations, people's entitlement as customers kind of shifted after COVID," Angie says. "In a sense, there was, I don't know, less joy. And there was less grace period for mistakes. Unless you were in the industry or went through those adjustments, I think that it's hard for people to see it.”

After The Guilty Plate reopened in June 2020, staffers were grieving their friend, brother and son at the same time as they were trying to run a restaurant. And it became impossible for them to separate the two.

“My brother is a direct loss from COVID. I think that that was hard for us to deal with, in a lot of ways," Michael says. "I don't want to get crazy on the political side, but there were people at the time that didn't know what had happened to our family. And they didn't want to deal with the COVID restrictions."

“There were times where I was out front and I literally had people say, ‘You believe that this is real?’ And what am I supposed to say when my brother had just passed away from the results of COVID? You know, I couldn't even speak.”

“I think we all kind of saw the writing on the wall.” Taylor says.

There were lots of reasons for the diner to close: Severely reduced seating, supply chain issues, health risks. Also, in the new restaurant economy where takeout is king, sit-down breakfast spots didn’t really stand a chance. But a main reason, ultimately, was the person who was no longer there in the kitchen with them.

“It's very difficult to, to go back into that restaurant, because we all spent, you know, hundreds, if not thousands, of hours there with Evan," Michael says. "And you see knives that he used, you see cutting boards that he's cleaned, you see the grill that he used to, you know, pour hours over, you see old handwriting that he has on inventory sheets that he used to have."

The Guilty Plate Diner closed for the second time in February of 2021. In June of 2022, the Alvanos family sold it. And, in September of 2022, it reopened under new ownership.

The current owner, Darrell Langworthy, says he faced staffing challenges at first, but they’re currently doing OK.

A salesman, an engineer and an architect walk out of a diner

“As far as the Alvanos-run Guilty Plate Diner, there's never ever going to be one like it, that's for sure. It is absolutely for sure,” says Angie Pierce, former server at the Guilty Plate.

Angie moved to the West Coast in 2021. She still picks up a few bartending shifts every once in a while, but she’s mostly focused on a totally new line of work: nature restoration.

“I work out in the fields, just pulling invasive species and replanting new growth, in hopes to have a healthier forest,” she says.

One of the reasons Angie was drawn towards this job? “You don't have to talk to anyone all day long if you don't want to. And I'm like, thank you! I like that."

Michael Alvanos, former co-owner of The Guilty Plate, is finally a full-time architect. He runs his own practice in Shelburne. “I mainly do single family and multifamily residential.”

Michael adds that his parents, George and Christine Alvanos, are now retired. They politely declined my request to talk for this story.

Taylor Courville, who spent nearly half his life working in restaurants with the Alvanos family, now works in sales for a company called Cintas. He mainly rents uniforms to businesses like mechanic shops and science labs. “And a lot of it's actually to restaurants,” he says. “Chef coats and aprons and stuff like that.”

Nick “Niko” Sobolev capitalized on all those conversations at The Guilty Plate about black holes by getting his physics degree from UVM. He recently moved to Delanson, New York where he works as a process engineer for GlobalFoundries.

Of course, the pandemic didn’t change everything. Much of the former diner staff is still in close contact.

“I'm still in contact daily, weekly, you know, with with this tight group, which is really hard to find," Angie says, "because I don't even stay in contact with, you know, people from my hometown. So, it's like, to find this group that just meshed so incredibly well together, regardless, like is insane.”

“Nowadays, I think I am far more apt to look at things on a short term basis because of the results of COVID," Michael says. "You know, things truly do have a beginning, a middle and an end. And I'm very grateful, you know, that I was able to be part of something that I think these guys, you know, were part of too and we had an extraordinary time with it."

Before leaving, I ask Niko and Taylor if they have that same type of familial relationship with their current colleagues.

“No. Absolutely not,” Niko says.

Taylor: “I think we would have been let go by now.”

_

Credits

Josh Crane reported and produced this episode, and did the mix and sound design. Editing and additional production from Lynne McCrae and the rest of the BLS team: Angela Evancie, Myra Flynn and Mae Nagusky. Ty Gibbons composed our theme music; other music by Blue Dot Sessions and XTaKeRuX.

Special thanks to Nicholas Martin and the other former restaurant workers who shared their stories with Brave Little State. Also thanks to our colleagues Bob Kinzel, Liam Elder-Connors, Henry Epp, Lexi Krupp, Nina Keck and Mark Davis.

As always, our journalism is better when you’re a part of it:

- Ask a question about Vermont

- Vote on the question you want us to tackle next

- Sign up for the BLS newsletter

- Say hi on Instagram and Reddit @bravestatevt

- Drop us an email: hello@bravelittlestate.org

- Make a gift to support people-powered journalism

- Tell your friends about the show!

Brave Little State is a production of Vermont Public.