Brave Little State is VPR's people-powered journalism show. We answer questions about Vermont that have been asked, and voted on, by our audience — because we think our journalism is better when you're a part of it.

Today we answer a question from Sam Leveston about a religion, and a people, who have often been overlooked.

Note: Our show is made for the ear. We recommend listening to the audio above if you're able! But we also provide a written version here.

Vermont’s Jewish history stretches back hundreds of years. While this is by no means an exhaustive account, there’s enough here that we’re breaking things up into chapters. Click below to jump to a specific section.

- Prologue: The Mourner’s Kaddish

- Chapter One: Members Of The Book

- Chapter Two: Little Jerusalem

- Chapter Three: Jewish Counter-Culture

- Chapter Four: A Synagogue Without Walls

- Chapter Five: A New Wave

- Epilogue: May Their Memory Be A Blessing

Subscribe to Brave Little State for free, so you never miss an episode:

Loading...

Prologue: The Mourner’s Kaddish

I’m Jewish and, while I don’t consider myself a deeply religious person, there are aspects of Judaism that have always resonated with me. There’s one in particular that reporting this story made me think about a lot. It’s not a single prayer. Rather, it’s an underlying value: The emphasis Judaism places on remembrance. Remembering the life someone lived. The person someone was. Even long after they die.

This feels especially relevant these days, two years and counting into a global pandemic on what feels, some days, like we’re on the precipice of World War III.

“We turn now, as always, to those we remember, those that are not with us,” said Rabbi David Edleson during a recent Friday night service at Temple Sinai in South Burlington.

Every week, Rabbi Edleson cedes the floor so anyone grieving the recent death of a loved one, or anyone remembering someone on the anniversary of their death, can say a few words in front of the entire congregation.

“Every time my pants are sagging, I will just hear her in my head: ‘Pull up your hoyzns [the Yiddish word for pants]!’” says one congregant named Adam, in honor of his grandmother, to much laughter.

“Bess was my father's youngest sibling,” says another congregant, Ed. “It strikes me above all that she exhibited love to everybody in our extended family, and our times with her were terrific…”

Grief and sadness go hand-in-hand with loss. But there’s also joy in remembering someone’s life. And, in Judaism, there’s an emphasis on doing all of this remembering in a group setting.

At Temple Sinai, Rabbi Edleson continues the service by turning to a prayer recited in honor of the deceased: “If you're in mourning, or have a yahrzeit [the anniversary of the death of a loved one], or it's your tradition to rise for those who might not have family, please rise in body or spirit for ‘The Mourners Kaddish.’”

“The Mourner’s Kaddish” can only be recited in groups of at least 10 people. This forces those grieving to come out of isolation, to join the community and share their grief.

“May God give comfort to those who are bereaved,” concludes Rabbi Edleson, “and may the wonderful people who shared, as well as those who didn't share, continue to remind us of what came before us and what, therefore, what we owe to what comes after us.”

At the start of my reporting for this episode, I put a call out to Jewish Vermonters about the aspects of Judaism that feel especially meaningful. I heard from Jessamyn West, a library technologist from Randolph, who likes being Jewish even though she doesn’t feel very religious.

“You can do the community stuff without having to do the religion stuff, and that's fair!” says West.

West has actually talked about her relationship to Judaism on Brave Little State in the past. ICYMI, check out our 2020 episode, “What’s the state of religion in Vermont?”

This time, she got back in touch to talk about how Judaism helped her figure out what to say to community members and friends when they experience a loss. “I'm one of those people, I can be kind of awkward,” West explains.

I can relate to West’s struggle. What do you say when you randomly run into an acquaintance who’s lost a loved one? What do you comment when someone posts about a loss on social media? What can you possible say that is both concise and meaningful?

“‘Thoughts and prayers,’ obviously, have been ruined by the last administration. And previous to that, right, it's like the emptiest of things to say,” West says.

She also considered what she describes as the “Christian” ways to respond. “You know, either ‘They’re with God now,’ which never felt good to me, or, you know, ‘Sorry for your loss.’ And I always thought that sounded really trite and pat. But I think for a lot of people, no, it's the etiquette, it's the ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ about working with people experiencing grief.”

West wasn’t satisfied. So, she turned to Judaism. And the way that Judaism deals with grief hit the sweet spot: “May their memory be a blessing.”

“To me, it’s just a way of saying, you know, I hope the good feelings that this person had in your life are things that can comfort you when you don't have that person,” she says

Sometimes people might say, “May their memory be for a blessing.” Same idea. In spite of its brevity, this simple phrase captures the Jewish approach to grief and remembrance really well. I’ve heard it said my whole life, but I’d never thought about it too deeply before talking to Jessamyn West. Now, I can’t stop thinking about it.

This phrase has offered me guidance and meaning throughout my efforts to document the history of an entire people in Vermont, a people who have long been shepherds of their own communal history, keenly aware of how they would be remembered and the legacy they’d leave behind, even as that history was playing out in real time.

So, let’s remember the Jewish people who lived Vermont history. Their memory is a blessing.

Chapter One: Members of the Book

For a long time, the story of Vermont’s first known Jewish congregation was stuck — literally — in Denver, Colorado, shoved into the drawer of a cabinet in an antique shop (or possibly a flea market). “I'm not exactly sure where he found it, but there was this minutes book,” says Robert Schine, a professor of Jewish Studies at Middlebury College since 1985.

He’s referring to a Denver-area Rabbi who stumbled across this book and sent it to the American Jewish Archives for safekeeping. Then, in 2007, Schine was helping the Slate Valley Museum develop a new exhibit about Jewish immigration in the region, which is when he first encountered it.

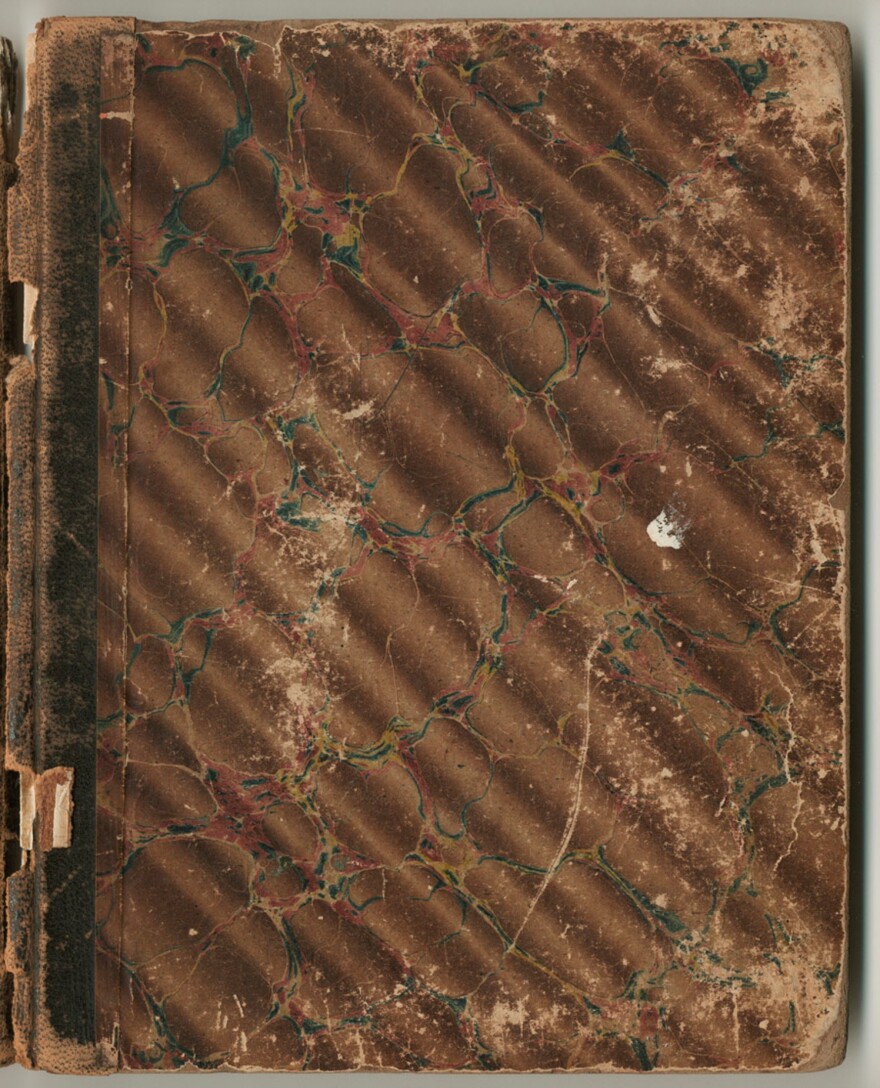

“It's a beautiful document,” Schine says, “It's got a kind of marbled cover, and it's somewhat yellowed paper, blue lines to guide your writing. And it's written with fountain pen.”

Schine could sense this book was important at first glance. And then, once he managed to identify the unique Judeo-German dialect the book’s authors were using (no small task), their words jumped off the pages. “And I could just hear them talking to one another, speaking their particular brand of German in this little town in Vermont, in the 19th century,” he says.

Schine would soon discover that this book is the earliest known evidence of organized Jewish life in Vermont. It’s a “minutes book,” a notebook filled with meeting notes and other important records from a 19th century Jewish community in Poultney, Vermont. To this day, no one knows how it got to Denver, but, more importantly, it is now back in Vermont (at least, a high resolution scan of it is).

The community that kept this book in the 1860s and 1870s is different from the early American Jewish immigrants that live in the popular imagination. Instead of settling in tenements in New York City’s Lower East Side, these Jews ventured north from the city, into the countryside, as pack peddlers.

Pack peddlers were like mobile, one-person general stores. They sold household supplies like needles and thread, pots and pans — basically, anything that would fit into a large backpack. Peddlers who persevered for long enough settled down in small, country towns and opened stores. Eventually, these stores dotted the Champlain Valley. But there were still plenty of Jewish pack peddlers who hadn’t settled down.

“And when the Sabbath came around,” Schine says, “Friday afternoons, they would seek a place to spend the Sabbath, since an observant Jew won't do business on the Sabbath and won't travel on the Sabbath and won't lug a backpack around on the Sabbath.”

It made sense for Jewish peddlers to spend Shabbat in a town where other Jews had already settled (remember, Judaism is practiced in groups). Very little is known about the early Jewish Vermont communities that emerged — the minutes book offers the earliest and most thorough accounting, according to Schine. It details, in real time, one community’s efforts to become a congregation: where to hold services, how to find a Torah, where to establish a Jewish cemetery and, of course, who paid for what.

Like most group projects, there was some tension. “It makes for amusing reading,” Schine says, “Anybody who's been involved in any church or synagogue or organization knows that there's usually a couple of people who do the work and others who benefit and are not so quick or eager to participate in the work.”

Prior to the Jews in Poultney, Schine says there were Jews in Burlington and Montpelier. But this particular community on the southwest border of Vermont is still the earliest organized Jewish community of which we have evidence.

“I think that this urge to keep a record indicates a kind of historical sense,” Schine explains. “They knew that what they were doing was, in their small world of Poultney, Vermont, historical! It was significant.”

It was significant, even without the trappings of more established religious communities, like an official house of worship. “They didn't have a building that was their synagogue,” he says, “but they refer to themselves as ‘the members of the book.’ So, in a way, the book established this community, this small community in the hinterlands of Vermont, a community that was part of ‘the people of the book.’”

Even though they didn’t have a synagogue, the Poultney Jewish community was big enough to split into two congregations over a deep disagreement. The very last entry in the book, dated Sept. 5, 1874, details those two factions reconciling. “It leads me to think that this reconstituted congregation perhaps started a new minutes book that we don't have,” Schine says.

Maybe it’s in a different antique shop in Denver.

“It is a remarkable story and a testimony to the importance of archives and of preserving one's history,” Schine says, “And I think that kind of nurturing of memory is really characteristically Jewish. Remember. Remember that you were slaves in Egypt. Remember who you are.”

After Sept. 5, 1874, there is little to document the exact fate of the Poultney Jewish community. What we do know is that Jewish communities across the rest of the state continued growing, bolstered by a second wave of American Jewish immigration beginning in the late 1800s.

_

Chapter Two: Little Jerusalem

My colleagues at Vermont PBS released a film in 2014 about the late 1800s and early 1900s in Burlington history, called Little Jerusalem. That was the old name for Burlington’s Old North End back when it was the heart of Vermont Judaism.

“The Burlington Jewish community almost entirely consists of a group of people from a couple of shtetls, small rural villages [inaudible] in Lithuania,” says Vermont historian Jeffrey Potash in the film.

In 1885, in the early days of Little Jerusalem, a group of Jews established Ohavi Zedek, Vermont’s first official Jewish house of worship. By the early 1900s, Little Jerusalem was bustling. Over 1,000 residents crammed into just a few city blocks. There were not one, but three total synagogues.

“What is distinctive about the Burlington Jewish community is the remarkably homogeneous nature of the residents,” Potash says, “I recall a lady who came here in the late 1930s. And she was from a larger Jewish community, I believe Boston or New York, and she said, ‘My God, this is suffocating.’ And everybody was both looking out for everyone, and ... knew everyone else's business.”

After World War II, Little Jerusalem started to fade. The younger generation of Jews – now second-generation Vermonters – spread out around the state and beyond. They weren’t as connected to the traditional lifestyle their grandparents had brought with them from Lithuania and, according to Jeffrey Potash, some openly rejected it. “For a while, the generations that left Little Jerusalem wanted to put it behind them.”

Now, however, there’s been a concerted effort to return to this history to make sure it doesn’t disappear forever. “I think we're returning to recognize that it was an important piece of the Vermont story,” Potash says, “Four synagogues in Burlington is a testimony to the fact that Little Jerusalem planted a seed of a vibrant and diverse Jewish community today.”

This community made international headlines in recent years when a rare mural from one of the now-defunct Little Jerusalem synagogues was rediscovered. It’s one of the last remaining examples in the world of an art form once popular in Eastern European synagogues, but which has now been nearly completely wiped out.

In 2014, former Vermont Governor Madeleine Kunin – who herself is Jewish – released a video supporting fundraising efforts to restore the mural to its original glory. “We are fortunate in Vermont to have such a treasure in our midst,” Governor Kunin says, “It really reminds us of who we are and who we were, both as Jews and as Vermonters.”

Today, the mural is in the final stages of conservation. It’s now installed at the entrance of Ohavi Zedek, Vermont’s oldest synagogue, which also boasts the largest congregation in Vermont -– about 300 families.

Chapter Three: Jewish counter-culture

“They didn't come to be Jewish, necessarily. They just came because they were hippies. And they happened to be Jewish,” says Rabbi Tobie Weisman, director of Jewish Communities of Vermont, our only statewide Jewish organization.

Rabbi Weisman explains the the 1970s were another major inflection point for Jews in the state. “There have been Jews who’ve moved to Vermont for over 100 years. But in the '70s, many Jews moved to Vermont, like Jewish hippies moved here to, you know, be Jewish and hippies.”

Jewish people moved to Vermont during this time as part of the “Back to the Land” movement. These were mostly people from places like Boston or New York City who wanted to live out their values in a different kind of environment.

More from Brave Little State: Those 'aging hippies' who moved to Vermont...Where are they now?

One such person was Avram Patt, Vermont state representative for the Lamoille-Washington district. Representative Patt grew up in a Yiddish household in the Bronx. “In my own background,'' he says, “the Yiddish was not just secular but was also Progressive, labor movement-oriented.”

As important as these Progressive values were (and still are) to Representative Patt, he says he learned from a young age that he was better suited to act on them somewhere other than New York City:

“I had attended two different Yiddish-oriented summer camps in upstate New York for two months every year. I spent a lot of time in the country for a city boy. I learned early on what a starry night actually looked like. And then, when I was a little bit older, I read Thoreau. And I really was, like, looking to get out of the city.”

Vermont was an obvious choice. So, he moved to Plainfield in 1970 and enrolled in Goddard College. Eventually, he connected to other Jewish Vermonters, many of whom were trained musicians. One day, one of his musical friends, Rick Winston, got an offer from the Barre Ethnic Heritage Festival.

“One of the organizers approached Rick Winston and said, ‘We haven't had any Jewish music at the Ethnic Heritage festival. What do you think?’” Representative Patt remembers Winston gathering a whole bunch of people to start practicing. He says he was invited because he was the only person that knew Yiddish songs, even though he played no instruments. “Right after we were done performing, people approached us and said, ‘So … do you do weddings? Can you get hired for a bar mitzvah?’ And we realized that maybe a few of us should get a little more serious about this, and practice a little more.”

Thus, the Nisht Geferlach Klezmer band was born. More than four decades later, they’re still performing. “Klezmer music is a form of Jewish music," Rep. Patt says, “[and] has its origins in Europe. A lot of it is dance tunes for simchas, for celebrations, weddings, bar mitzvahs and stuff like that.”

Performing with Nisht Geferlach (which, by the way, got its name from a sarcastic Yiddish phrase that roughly translates to “It won’t kill you”) helps Patt stay connected to his Yiddish roots. But, he’s quick to point out that Vermont has Jewish roots of its own, which is something he didn’t appreciate when he first came here in the '70s. “I thought I was coming to a place where that none of that existed, and it does,” he says. “You know, it's not hiding.”

Chapter Four: A synagogue without walls

“It was purely a matter of accident that we wound up in Vermont,” says R.D. Eno from his home in Cabot.

Like many who migrated to Vermont in the ‘70s, Eno grew up in New York City. Unlike many others, however, he and his wife didn’t choose Vermont. At least, not really. They’d been living abroad for a few years and, when they found out they’d have to move back to the States, “we threw darts at a map, essentially, and came up with New England, which was a place neither of us had ever lived.”

I’m fascinated by R.D. Eno because he’s not the kind of person I’d have expected to help transform Jewish life across an entire region. “I never wanted to take myself too seriously!” he says, “I'm not a rabbi. I’m just a guy.”

It turns out, those are exactly the qualities that made Eno perfectly suited for the job.

“The one thing I really dislike is piety,” Eno says, “And that was something I wanted to avoid in everything I wrote, in everything I tried to promote … There's something innately humorous — comic, certainly, as opposed to tragic — in the presence of Jews and Judaism in the unfamiliar regions of New England. I tried to make that fun.”

Eno succeeded in making Judaism fun. But that wasn’t his original goal. When he first moved to Vermont, he didn’t seek out the Jewish community at all. Around 1981, he was recruited into a Jewish brunch group in Montpelier, which he describes as an alternative to Montpelier’s Beth Jacob synagogue, “which was still pretty much the province of the older generation who had kept the synagogue going since the early 20th century.”

Through this brunch group, Eno met kindred spirits: Montpelier-area Jews who didn’t conform to traditional Jewish ritual life, but, nonetheless, who had an appetite for Judaism in some form. “Somehow the idea began to germinate, a calling together of Jews in rural areas to form a kind of synagogue without walls,” Eno says.

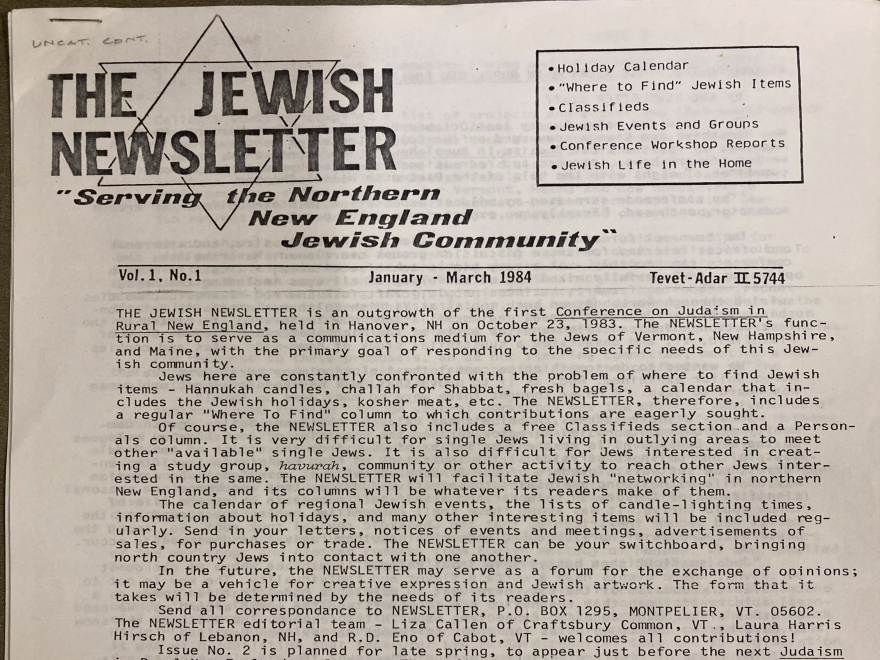

The “synagogue without walls” took the form of a conference. The first Conference on Judaism in Rural New England took place in 1983 at Dartmouth College.

“We expected perhaps 100 people. And 250 people showed up,” Eno says, “As I recall, it was pretty chaotic.” Nevertheless, the idea resonated. “The idea of building Judaism from the ground up was tremendously exciting. It was that excitement that propelled our little steering committee forward.”

They started publishing a newsletter for Jews across New England. And they held their second annual conference at Goddard College in 1984. “And the second conference was even more exciting than the first,” Eno says, “People stayed over. We had dormitory accommodations. It was a full weekend affair.”

Even then, Eno says he knew that that weekend was a real moment in the development of a modern rural Jewish identity:

“In our weekend conference, we acquired, I think, a sense of destiny, participating in Jewish history in a most vital and important way. And that gave us the momentum to carry on for the next 20 years.”

Soon, the conference moved to Lyndon State, its most permanent home. Rabbi Tobie Weisman was part of the conference’s board in the 1990s. “Jews would come to get together because there was nothing for them happening near where they lived all year long,” she says, “and they would just have this one weekend.”

According to Rabbi Weisman, the word “conference” doesn’t really do it full justice. “It was kind of like going to Jewish summer camp, yeah, for the weekend.”

Jewish summer camp or, maybe, a multi-day Jewish frat party?

“The dorms were pretty basic. You could hear everything going on in everyone's rooms, in the hallways, you know, it wasn't like, it wasn't a place where you got a lot of sleep,” Rabbi Weisman says. The conference also featured concerts (the Nisht Geferlach Klezmer band performed more than once) and art exhibitions. “There was a lot of singing and celebrating and people would stay up for hours and hours into the night talking. It was so exciting because you got to see these wonderful people that you didn't see all year, and get to hear about their lives and their communities.”

“And they are still my friends,” Rabbi Weisman says.

Beyond the socializing and celebrating, there was also plenty of educational programming, which was as Vermont-y as it gets (in a Jewish sort of way). Over the years, workshops ranged from “Why I Am Not In Services: Alternative Ways of Expressing Jewish Spirituality” and “The Vegetarian Consciousness in Judaism” to “Spiritual Menopause” and “How To Dance at a Jewish Wedding.”

R.D. Eno is quick to point out that there were also workshops and services geared towards more Conservative and Orthodox Jews. “I think it was our objective to create a trans-denominational Jewish experience,” he says, “That was part of the vision. There are so few of us in New England, there really isn't enough of us to endure denominational rivalry.”

Over the years, the conference grew and grew. Prominent Vermont Jewish figures like Madeleine Kunin, Bernie Sanders and Julius Lester participated. Notable Jewish journalist Wolf Blitzer would show up from time to time too. And Rabbis and other Jewish clergy from across the Northeast would make the trip. Eventually, so did Jews from Montreal.

“Jews everywhere recognize the need for community in order to affirm and practice Jewish identity,” Eno says, “The conference is simply an expression of what Jews do everywhere. As soon as there's a handful of Jews, there's a congregation. In fact, if you get one more than a handful, you generally have two congregations!”

Those Jews who burned the midnight oil in the Lyndon State dorm rooms for one weekend in June each year left with a renewed sense of inspiration and connection — feelings that remained throughout the year, long after that one euphoric weekend had ended.

“I did notice that the conference seemed to encourage the development of more conventional Jewish communities around the region,” Eno says.

After close to a decade, R.D. Eno left the conference organizing committee to focus on publishing a regional Jewish newspaper (or “newsmagazine” as he called it), entitled K’Fari, meaning “our town” in Hebrew. “And I went all over New England, interviewing Jews in the countryside, covering Jewish events, in fact, covering the founding of new Jewish communities,” Eno says.

By the early 2000s, both the Conference on Judaism in Rural New England and K’Fari had petered out. It’s hard to get a straight answer as to why — a lack of funding was a factor. As was a feeling that they had simply run their course.

“People were just pretty much burned out,” Eno says, “There were all of these new Jewish communities around New England. And Jews had found any number of ways to affirm their identity and their sense of community. The conference wasn't necessary anymore."

“By that time, it is true that we did have more synagogues,” Rabbi Weisman says, “We did have more Jewish life going on. It wasn't as hard to be Jewish in Vermont by then.”

Even if it seemed like the right time for the conference to fade, not everyone was happy about it. “When the conference ended, I was so sad,” Rabbi Weisman says, “So sad. I mean, people were so sad about it.”

Chapter Five: A new wave

There are 19 formal Jewish congregations around Vermont, as well as a handful of informal communities, according to Susan Leff, president of Temple Sinai in South Burlington and the founder of Jewish Communities of Vermont. She also estimates, conservatively, that there are about 20,000 Jews living here today. This might not sound like a lot — it’s just 3% of the total Vermont population — but consider that Jews make up less than 2.5% of the U.S. population and only about .19% of the world population.

Over the last few years, the pandemic has led to a new influx of Jews moving to Vermont, part of the wave of young people who continue to become disillusioned with city life. I was one of those people. I moved here in the summer of 2021 after spending most of my life in Boston.

A few months after I got here, Sam Leveston arrived from the Bay Area. “Being Jewish is a big part of my identity and who I am,” she says.

Leveston is Brave Little State's latest winning question-asker, a.k.a. the person whose curiosity sent me on this quest to explore Vermont’s Jewish history. “I'm back in Vermont. I'm trying to, like, re-establish my roots and build my community again.”

Leveston attended the University of Vermont for undergrad, left for a few years, and now she’s back. Her interest in Vermont’s Jewish past is motivated by her desire to feel truly comfortable and welcomed here in the present. “The first thing I've been thinking about is, you know, how do I tap into the warmth of the Jewish community here and what does that look like?” she says. “What's its history?”

One of the things that has stood out to Leveston the most since moving back to Vermont is how some Vermont Jews connect — or, rather, don’t — to their Judaism. “Like, I'm super open about being Jewish, but I've met a lot of people who have some Jewish heritage, but they don't view it as their identity,” she says.

Leveston isn’t alone in her observation. A sense of apathy among Vermont Jews is a theme that came up in multiple conversations during my reporting. It’s not a new trend.

“In the rural areas growing up, if you have any amount of antisemitism, it's much easier for them to become apathetic about their Judaism than in a in a larger area,” says a woman in a 1978 recording stored at the Vermont Historical Society. (Thanks to VHS cataloguer Kate Phillips for the assist.) It was a discussion among a group of Montpelier-area Jews about Jewish life in Vermont.

“... and if you’re talking about rural Judaism here, the apathy problem, I think, is ... directly related to the antisemitism problem,” the woman continues.

It’s impossible to tell a complete story about Vermont Jewish history without acknowledging the role antisemitism has played on both an interpersonal and systemic level. In the 1930s, for instance, a statewide referendum for a scenic road atop the Green Mountains was defeated, in part, over concerns that Vermont would turn into the Catskills: filled with Jewish vacationers from New York City. Also, as a policy, Jews weren’t allowed in many Vermont hotels until at least the 1950s. “No Hebrews Allowed,” or “Gentiles Only” were often included in hotel ads and on signs.

Antisemitism in Vermont isn’t just a thing of the past — the Anti-Defamation League, which tracks anti-semitism, has recorded nearly 30 anti-semitic incidents since 2017. Incidents involving swastikas and hate speech, among other things.

Whether or not antisemitism, or a fear of antisemitism, is the cause of religious and cultural apathy in Vermont’s Jewish population, Rabbi Weisman thinks it’s a problem.

“The most common form of despair is not being who you are,” she says, quoting the philosopher Søren

Kierkegaard.

In Vermont, many people don’t know Jewish people personally, let alone what practicing Judaism looks like. “It makes you feel kind of like an outsider,” Weisman says.

Rabbi Weisman has a message for Vermont Jews who don’t feel very “Jewish:”

“You might just be a cultural Jew, but there's something about being Jewish that is different. And, so, just to be around other Jews, celebrating being Jewish, it's important. Really, really important."

Our winning question-asker, Sam Leveston, has been searching for the type of Jewish connection for which Rabbi Weisman is advocating. She’s considering joining a congregation, “but I'm also curious about maybe building something or creating something that is a little less formal,” she says.

Well, there’s a lot of precedent for Vermont Jewish life existing outside the bounds of more traditional congregations. Vermont Judaism has always been shaped more by individuals than by a handful of long-standing institutions, be it a network of Jews from across rural New England searching for a new type of connection, a Burlington neighborhood filled with Jews holding onto their Lithuanian heritage in a strange land, or Jews looking for a warm bed in Poultney to take a break from the pack peddler lifestyle.

I’ve come to think of Vermont Judaism as a type of “choose your own adventure,” which is an approach that is especially necessary in more remote areas.

“You get a lot of freedom here to define what Judaism means to you,” says Ira Wolf, a para-educator at the St. Johnsbury School.

Wolf grew up in an Orthodox Jewish community in New York City, where that type of freedom didn’t exist. He says one either has to subscribe to Orthodox community norms or risk losing their entire social network and support system. So, when he was faced with this decision, he left and moved to Vermont so he could live out a Jewish life on his own terms. “I like it better than being Jewish in New York City,” Wolf says.

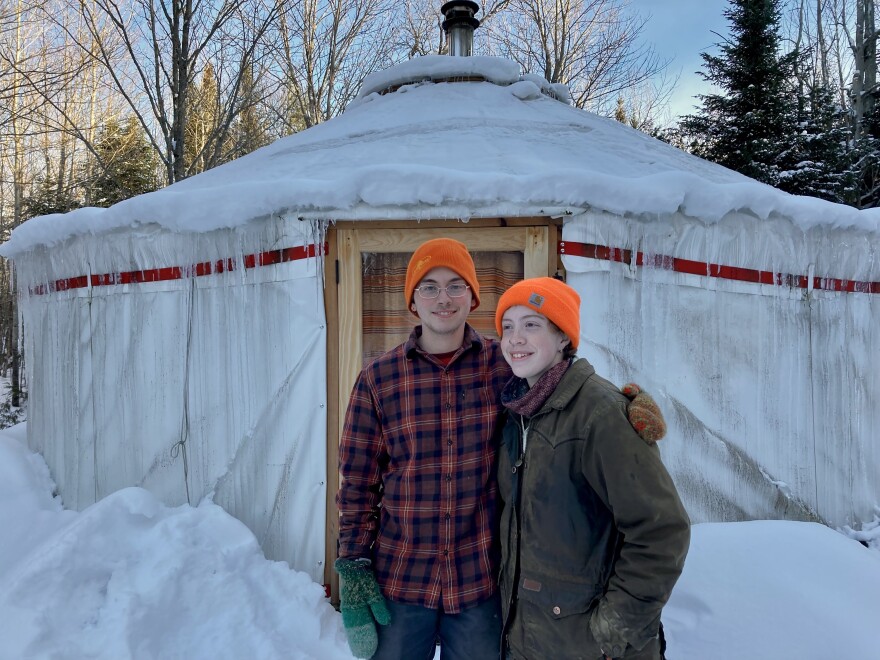

Ira lives with his wife, Nelly Wolf, in a yurt in Barnet, near the southern end of the Northeast Kingdom. Nelly feels like Jewish life beyond Vermont’s major population centers often gets overlooked in discussions about Judaism in the state. “To me, these more rural, underfunded, often lay-led shuls are the essence of what it’s like to practice in Vermont,” she wrote in an email.

I visited the two of them in their home to learn more about rural Vermont Jewish life. The freedom they both recognize in Vermont’s Jewish communities relates to a spirit of inclusivity that is not only a testament to the people who practice it, but also to the need for self-preservation. “You can't just expect the [Jewish] community to be there,” says Nelly, who grew up in an atheist household in Brattleboro and converted to Judaism more recently. “You have to draw the community to you every time.”

Vermont Judaism never was, and still isn’t, inevitable. As Ira puts it, “It’s not something that you do because your neighbors do it. Because your neighbors are not doing it and do not know why you are.”

“There is so much more kind of communal Judaism [in Vermont],” Nelly says. “Like, we have been asked to attend shul on certain Saturday mornings so that there will be enough people to say the 'Mourner’s Kaddish.'”

Recently, Nelly found a new way to connect with Judaism in Vermont and beyond. She’s a weaver by trade, and a little over a year ago, she founded Black Cat Judaica: a company that makes and sells tallit — Jewish prayer shawls. “And it's been going gangbusters ever since, pretty much,” she says.

Meeting Nelly and Ira Wolf, I was struck by the sense of responsibility they feel to educate those who aren’t familiar with Jewish tradition. Passover, for instance, a holiday commemorating the exodus of Jews from slavery in Egypt, is a prime opportunity. They’ve been hosting their own Passover Seders for the last couple years. “It's a really great opportunity to sort of share Judaism with other people who aren't necessarily Jewish,” Ira says. In fact, most of the people who join Nelly and Ira at their home for Jewish holidays are not themselves Jewish.

Epilogue: May their memory be a blessing

At the end of my reporting on Vermont Jewish history, I traveled to Town Hill Road in East Poultney, Vermont. On one side of the road is the well-marked, well-maintained East Poultney cemetery. On the other side, the East Poultney Jewish Cemetery, Vermont’s oldest Jewish cemetery, is an unmarked plot of land fronted by a nondescript metal fence. If I hadn’t known better, I’d have worried I was trespassing.

Fortunately, I had a well-qualified tour guide. “So, as we enter in right here, we're going into the back-most corner of the cemetery on the left side,” says Netanel Crispe, a 19-year-old ultra-Orthodox Jew from nearby Danby,

This cemetery is one of the last and best reminders that the Poultney Jewish community, the people of Vermont’s earliest known Jewish congregation, were real.

“And we have two really incredible pieces of history here,” Crispe says, ushering me over to two headstones in the corner. “The stones of Marcus or Mordecai Cane and his wife.”

Marcus Cane was born in 1793 in Hessen, Germany, and was buried in 1874 in East Poultney, Vermont, as a retired pack peddler, a founding member of Vermont’s earliest known Jewish congregation. He was the first person buried in this cemetery.

It wouldn’t have been possible for me to visit this place just a few years ago: Barely anyone in town knew it existed, and even those who had heard about it didn’t really know where to find it. Then, my tour guide, Netanel Crispe, came along. “One of people's, kind of, greatest fears is being forgotten,” he says, “And I think that really is true across the board for all people, it's just human nature.”

Even though he’s still a teenager, Crispe serves as a trustee at various historical societies around the state. He’s big into metal detecting, and works with the societies to dig up relevant artifacts. During one of his metal detecting excursions in the summer of 2020, he got a tip about an old Jewish cemetery here in East Poultney, “which was news to me,” he says, “I've lived here for eight years, just down the road, I'm a 10th generation Vermonter, I've spent years in Poultney, and I never had a clue that this was here. So that immediately was like, ‘Wow, I gotta find this. I want to know what it is.’”

It took him multiple attempts to locate it. The entire plot of land was overgrown and had fallen into disrepair. So, even though he was still in high school at the time, he decided to do something about it. He would even leave school early from time to time (with the blessing of his teachers, I learned when I reached out to the school). “So I'd come and just was hauling out debris and brush, doing meetings and things of that nature.”

The restoration effort snowballed from there: Crispe has raised nearly $20,000 to date to support the work. Last fall, he gathered 25 volunteers to spend a full day cleaning and resetting the headstones, many of which had broken into pieces or fallen over. “We had to pick all these stones up, some of them weighing over 400 or 500 pounds, dig out a new foundation for them, make sure that that was level and put the stones back,” Crispe says, “which was a very tremendous process to do by hand.”

Crispe is a current freshman at Yale University, but he’s managed to keep up his work on the cemetery. He’s started to digitize cemetery records and has plans to install a new gate at the front of the cemetery with proper signage so people can find it more easily. Also on the docket: registering the cemetery as an official State Historic Site.

Throughout this work, Crispe has heard from dozens of descendants of the families buried in the cemetery. “Some of them in their 80s and even 90s came out and volunteered,” he says.

“Hearing their stories, this was no longer I'm cleaning a headstone of some stranger, this is kind of a testament and a marker to that individual, their life, their story, which is something that not only should be documented, but appreciated, learned from and preserved long-term.”

The East Poultney Jewish Cemetery is a fitting place to end this story: to remember the roots of Judaism in Vermont, and also to recognize how fragile memory and the preservation of history can be.

“It's very peaceful up here,” Crispe says, “We’re on kind of this back road. I just I love being here.” He even showed up 15 minutes early for our interview, just so he could walk around take it all in. “Knowing how this looked before and how it looks now,” he says, “it’s wonderful.”

Further resources:

- Jewish Communities of Vermont

- New England Jewish History Collaborative

- The Center for Small Town Jewish Life

- Schine, Robert. "'Members of this Book': The Pinkas of Vermont's First Jewish Congregation" (American Jewish Archives Journal, 2008)

- "The Journey of the Lost Mural: An International Treasure in Vermont"

- DAVAR: The Vermont Jewish Women's History Project

- The Slate Valley Museum

- The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives

- Philip Hoff: How Red Turned Blue in the Green Mountain State by Samuel Hand, Anthony Marro and Stephen Terry (2011)

- East Poultney Jewish Cemetery records

Want more Brave Little State? Subscribe to our podcast for free:

Loading...

Credits:

Thanks to Sam Leveston for the great question.

Josh Crane reported this episode and did the mix and sound design. Additional production and editing from the rest of the Brave Little State team: Angela Evancie, Myra Flynn and VPR News Fellow Marlon Hyde. Ty Gibbons composed our theme music; other music by Myra Flynn, Blue Dot Sessions, and the Nisht Geferlach Klezmer Band.

Special thanks to Bruce Post, Paul Carnahan, Kate Phillips, Sue Halpern, Rabbi Linda Motzkin, Rabbi Jonathan Rubenstein, Stacie Gabert, Mikaela Lefrak, Mary Engisch, and Robert Resnik. Thanks also to everyone who reached out about this story to Brave Little State on social media: that’s Thomas Hudspeth, Marc Estrin, Alison Novak, Alex Venet, Rachel Stoll, Selene Hofer-Shall, Jonah Ibson and Suzie Felber.

As always, our journalism is better when you’re a part of it.

- Ask a question about Vermont

- Vote on which question we should answer next

- Sign up for the BLS newsletter

- Say hi on Twitter, Instagram and reddit @bravestatevt

- Drop us an email: hello@bravelittlestate.org

- Make a gift to support people-powered journalism

- Tell your friends about the show!

Brave Little State is a production of Vermont Public Radio.