This month’s question led Brave Little State straight into an unfolding story — about an outsider with deep pockets and big ideas, and the towns that banded together to reject those ideas.

And now that their efforts have paid off, what happens next?

Editor’s note: As always, we recommend listening to the episode!

A formative place

If you go to the Joseph Smith Birthplace Memorial, in South Royalton, something hits you as soon as you step out of your car. It’s barely loud enough to register at first. But then it’s all you can hear: these angelic voices.

You realize there’s a network of speakers hidden in the trees. And this beautiful sound is just wafting through the air as you walk around.

Joseph Smith was the founder of the Mormon religion, and he was born right here in Vermont. There’s a giant granite obelisk at this memorial; people come here by the thousands every year to pray or meditate or just check out the scene.

Brave Little State came here with this month’s question-asker, Jillian Conner.

When we looked around for someone to talk to, we were greeted by Elder Hobbs. An elder is an order in the Mormon priesthood, and Elder Hobbs is incredibly hospitable. He walks us through this little museum and tells us about the life of Joseph Smith. (There’s a little proselytizing, too, as he offers us copies of the Book of Mormon.)

We can’t help but ask about the choir music emanating from the trees, and it turns out it is not from Elder Hobbs’ playlist.

“It’s all controlled from Salt Lake. We don’t have anything to do with it,” he says. “They just turn it on at about 8:30 in the morning, [and it] plays until about 11 o’clock at night.”

It’s clear they’re trying to curate an experience here at the memorial. And this place had a profound impact on a guy named David Hall.

Hall lives in Utah now. But he grew up in upstate New York and came here as a kid with his Mormon family. And he kind of imprinted on the place.

“It wasn’t that far of a drive for us from Schenectady, growing up. They had some campgrounds, so we would camp there,” Hall recalls. “And then I’ve just followed Vermont carefully, you know, through my life.”

David Hall is the reason we visited the Joseph Smith Memorial. Hall is a wealthy businessman. And a few years ago, he came to town with some big plans for the land around the memorial. He wanted to build a kind of eco-utopia, where people would live in energy efficient structures and grow all their own food on community farms. He was going to call it “NewVistas.”

Hall began buying up parcels in four small towns surrounding Smith’s birthplace: Tunbridge, Royalton, Sharon and Strafford. And the thing that really got people’s attention was that, eventually, Hall wanted 20,000 people to live there, on 5,000 acres.

And that brings us to this month’s question, from Jillian, who happens to live in Tunbridge:

"What is the deal with the NewVistas Foundation and its plan for Central Vermont?" — Jillian Conner, Tunbridge

That’s what this episode was going to be about. How is a developer from Utah going to remake central Vermont into an ecologically sustainable utopia?

And then, just when we finished writing the script, David Hall dropped a little bit of a bombshell on us: He announced that he’s decided to sell all the land he’s bought up. The local opposition over the past two years has been a little fiercer than he anticipated.

“Those who are opposing my dream did a really good job, so I tip my hat to them,” he told us.

So that’s it. David Hall is done with Vermont. But, the story of NewVistas isn’t over yet.

Subscribe to Brave Little State:

Loading...

Meet our question-asker

It turned out that Jillian Conner had an agenda when she asked her question.

“I have to be honest. I partially know the answer to my question. The reason I asked it was to sort of bring awareness to the issue,” she said.

Jillian and her partner moved to Tunbridge last July. They bought 80 acres, with plans to farm. Tunbridge is one of the four towns where David Hall had also been buying land — Jillian figured this out when she saw signs around that said “No NewVistas.”

“We thought it was pertaining to anti-flatlander-moving-in type of movement, you know, opposed to people putting up new houses and destroying our beautiful vistas that we have in Vermont,” Jillian says. “And when I went home and Googled it, I realized what it was actually about.”

The opposition to Hall’s plan had been swift and intense. By the time Jillian moved to Tunbridge, residents of the four towns had rallied. They’d held non-binding Town Meeting votes. Many had vowed not to sell their land to David Hall. And they’d formed an opposition group called the Alliance for Vermont Communities — all to send the the message: No NewVistas.

When Jillian read up on everything, she decided she too wanted no NewVistas. She actually told us she was loosely connected to the Alliance for Vermont Communities. We’ll hear more about this opposition later. But to be clear, Jillian was not speaking for the Alliance when she talked about her own views on Hall’s proposal:

“I think the land use is definitely a huge part of my concern, and also the political sway. I think freedom of religion is a great right that we all have, though at the same time, conservative Christianity definitely tends to preach views that I disagree with.”

Jillian was worried about the Mormon connection — even though David Hall had said that the NewVistas communities wouldn’t have any religious affiliation.

“And it's not a quality I'm proud of, because … I like to think I have progressive views — ‘progressive views’ -— on how we should treat people who are different from us or not from the same place that we are. I’ve also traveled many places and I’ve been the stranger in many places. So, yeah ... Those two sides of myself have really been fighting over how to handle, like, newcomers — but to this scale, which is an enormous, huge scale.”

We want to give props to Jillian because it is not easy to admit that you have views that you yourself disapprove of. But that’s what’s so fascinating about NewVistas. Whether it was the developer or the nature of his plan or the sheer scale of change this would have brought to central Vermont if it actually happened, this topic really got people going. And it gave us a lot to cover.

Loading...

What is NewVistas?

If you live in central Vermont, or follow the news from this part of the state, NewVistas has probably been on your radar for a while. But in case you’re not familiar, here’s a bit more background.

Back in 2016, John Echeverria, an attorney and a professor at Vermont Law School, gave a presentation about Hall and the NewVistas Foundation at a meeting of the Strafford Conservation Commission. His 44-minute talk is on YouTube — and as far as Hall’s development plan went, it answered the question “What’s the deal with New Vistas?” pretty well.

“So, what is NewVista? This is not — not — a small idea. This is a big idea,” Echeverria said. “The goal of this venture is to achieve global environmental balance. Global ecological balance.”

John covered who David Hall is: “David Hall, an engineer from Utah, who is the primary mover behind this project.”

Hall built his career on something that his dad helped invent: the synthetic diamond. It’s used for all sorts of things now, including drilling for oil and gas. Hall ran a business that focused on this use: developing and selling drilling technology.

A few years ago he sold it to a company called Schlumberger, “which is the largest oil services firm in the world, for an undisclosed sum,” Echeverria said. “According to Hall, at least $100 million of the proceeds have been dumped into the NewVista Foundation, which is bankrolling this effort.”

So. A man whose fortune comes from fossil fuel extraction is devoting himself to a kind of environmental crusade. (Quick side note here: Hall’s dad kind did the same thing. According to his obituary in the Washington Post, after he retired, he became a tree farmer.)

Now for the what. What was David Hall actually planning for Vermont?

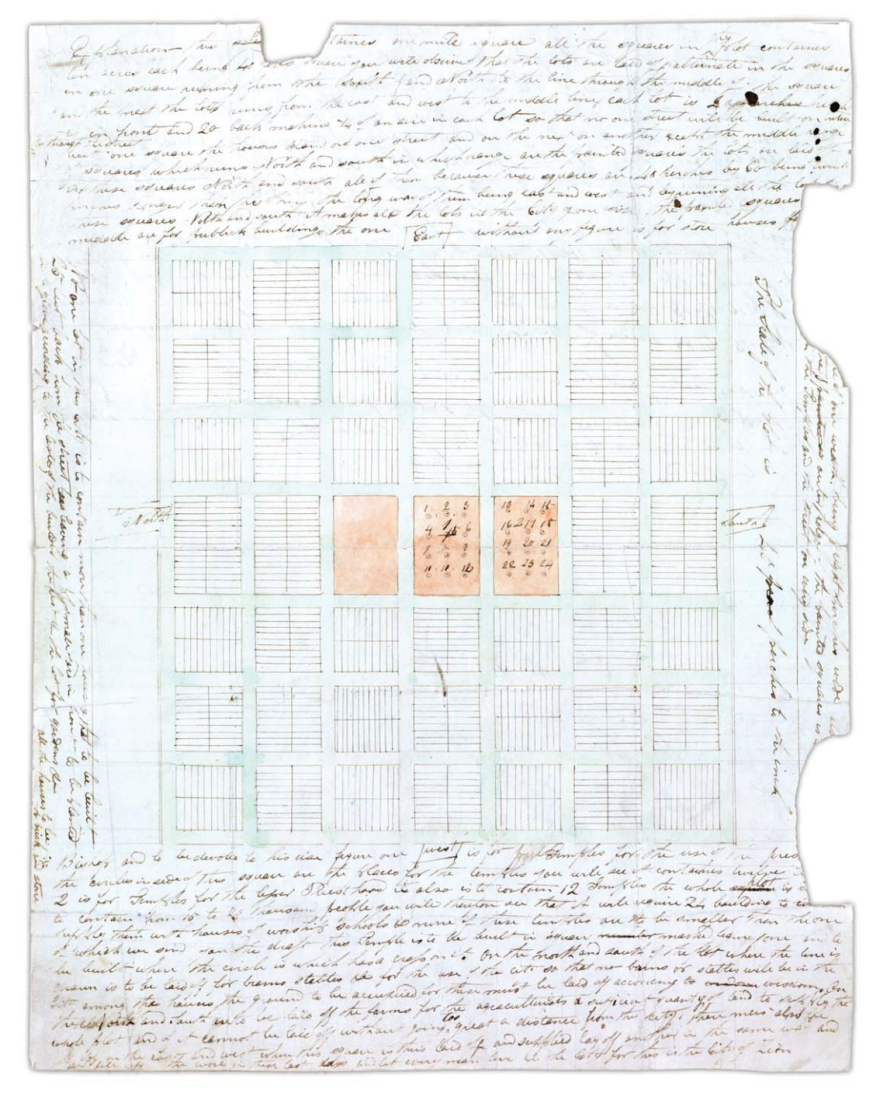

“The cornerstone of the building project is the community,” Echeverria said. He pulled up a slide of a city layout, shaped like a diamond. This is the community Hall envisioned for central Vermont, where up to 20,000 people would live.

“That would be a density of development that’s about 300 times the density of Strafford,” Echeverria said.

In the middle of the community would be homes and businesses: “And then there are these four triangles around the edge which are for intensive agriculture and industrial and animal husbandry,” Echeverria said. “And even a drilling block.”

Small living spaces and local energy, industry and agriculture — though not the kind of agriculture Vermont is known for:

“The suggestion is that a cow would never see the light of day in one of these communities,” Echeverria said. “Maybe a rabbit, maybe a chicken. Lots of grain, no high-protein meats.”

The design is super specific, with different-sized units all building up to a larger whole. Theoretically, you’d build one, and then another, and then another.

“The idea is, this is a model for human existence that should be embraced worldwide, in which billions of people would live. And if we did this, then the world would be saved. And it all can begin here in the hills of Tunbridge and Strafford. OK?” Echeverria said, to some laughter in the Strafford audience. “The guy’s not kidding around. I mean, you’ve got to give him credit, you know, he’s not thinking small.”

John Echeverria is on the board of the Alliance for Vermont Communities, that group we mentioned that lead the resistance to NewVistas. But you can’t tell by the way he made this presentation that he’s opposed to Hall’s plan.

“I think it’s fair to say that Mr. Hall, from all appearances, has a really genuine concern about the plight of the planet, and is trying to move forward an agenda, which, whatever its problems, is well-intentioned,” Echeverria said. “I think he also deserves credit for approaching this venture in a totally guileless way. He’s been quite willing to communicate with people ... even in the face of some fairly blistering criticism.”

The Plat of Zion blueprint

David Hall was quite willing to communicate with Brave Little State. He went into a studio in Utah, where he lives, to talk to us — again, before he changed his mind about Vermont.

To really wrap your head around what Hall was trying to do with NewVistas, you have to understand the genesis of the project. It came from documents from the 1830s.

“The documents have a front and a back, and if you take all of the phrases, and triangulate them with each other, you can reduce to practice details like the exact chair size, which happens to be 24 inches square,” Hall says.

The documents are called the Plat of Zion. They were created by Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, whose birthplace had such an influence on David Hall. These documents had an influence on Hall, too — in fact, they’re kind of an obsession for him.

“The more I studied them as an engineer,” he says, “the more I realized there was a lot more in the documents than the face value.”

Hall says there are hidden directions in there, that need to be deciphered like a codex. For example: Walls on buildings are supposed to be three-quarters of an inch thick. And there are supposed to be special toilets, to analyze what comes out of you when you go to the bathroom. (Hall’s engineering company is currently working on a prototype.)

The point here is that Hall wants his NewVistas community to be an absolute replica of the Plat of Zion. Because he thinks it’s the key to humanity’s future.

“It’s really a world treasure from my point of view for us to figure out how to use it to create truly green communities for the future,” he says.

And that brings us to a complicated paradox that underpins the whole NewVistas story. And that paradox is that David Hall’s vision in some ways has nothing to do with Mormonism. And in other ways, it has everything to do with Mormonism. The part of NewVistas that does have to do with religion, obviously, is its connection with the Plat of Zion.

“The prophet is going to dictate what the city is going to look like, how big the lots are going to be, how many streets there are going to be, how large should the city be,” says Benjamin Park, an assistant professor of American religious history at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas.

Park says Smith came up with the Plat when he was trying to start a Mormon community from scratch, in Missouri. But the thing is, even Joseph Smith doesn’t get true credit for the Plat of Zion. According to Mormon theology, Smith was a prophet, with a direct line to the voice of God. And it’s God who transmitted this whole Plat of Zion concept to Joseph Smith, sort of like a divine urban planning blueprint.

“This is one of the most fascinating things. It is very specific,” Park says. “It is saying how large the plots are supposed to be. It’s saying how wide individual plots [should be], how deep.”

And Smith’s design for the Plat of Zion isn’t confined to building specifications. It calls for a new kind of governance structure, as well. Benjamin Park says there are no civic buildings in Smith’s Plat. Nothing at all, actually, that’s set aside for democratic institutions.

“Which doesn’t make sense until you realize that in Joseph Smith’s view, the church and the state were merged,” Park says. “The same people who are going to be leading the religious sphere are also going to be leading the civic sphere.”

So, David Hall has modeled NewVistas after a city of God. But, here’s where the Mormon connection begins to dissolve: David Hall says his concept has nothing to with Mormonism at all. He says this whole enterprise is about a global model for coexisting with the earth. And that that means it needs to welcome of people of any faith — or even no faith at all.

“Otherwise, how does a Muslim come in? Or how does, you know, an agnostic come in, and stuff like that,” Hall says.

That humans are meant to live as Joseph Smith envisioned is a matter of providence and faith for David Hall. And it definitely takes a lot of faith to believe in the NewVistas concept.

We tried over and over again to get Hall to explain to us how this was all going to happen — the specific actions that would eventually culminate in this 20,000-person community in rural Vermont. We just couldn’t make heads or tails of how he intended to get there. And here’s where we finally ended up:

“OK, here’s an analogy that may not make sense to you but it makes sense to me, alright? We have 24 chromosomes in our system that makes up our biology, right?" Hall said.

Just like chromosomes are the building blocks of human beings, David Hall says the Plat of Zion provides the building blocks for human civilization:

“Here are the key elements, the chromosomes, you know, that are going to come together to create that community that we need for sustainability and scalability.”

Loading...

And that brings us to yet another paradox to untangle: Mormonism may be the religion that gave birth to the whole Plat of Zion concept, but Benjamin Park says even Mormons don’t think the Plat of Zion should be taken literally. The church has publicly disavowed any connection with David Hall and his NewVistas plans.

We and Jillian actually broached the subject with Elder Hobbs when we were at the Joseph Smith Memorial.

“It has absolutely nothing to do with the Church,” Hobbs said. “He’s a member of the Church, but he has nothing to do with it as far as the Church backing him. ... It’s entirely his own agency, his own choice. He’s just a guy with a lot of money who wants to do some sort of development.”

And professor Benjamin Park says most members of the church today don’t even know the Plat of Zion exists. We should note here that Park once worked for Hall’s NewVistas Foundation as a historical consultant. His tenure there was short. But, here’s Park’s take on the situation:

“When you talk about the NewVistas and Dave Hall, I think it’s fascinating to look at him as an example of this persistence of Zion thinking in Mormon thought, while also what makes him so odd and unique is he also represents what Mormonism has left behind.”

The opposition

It’s clear that David Hall is on his own wavelength. And when it came to his plans for Vermont, he figured Strafford, Sharon, Royalton and Tunbridge could be just the beginning.

Before he changed his mind about Vermont, he told us that Vermont could have 20 million people in 20 NewVistas communities. He also said he was in no rush.

“I would think that's out there at least, like I've said many times, at least 75 to 100 years, because the Vermont laws are very strict when it comes to development.”

The strict law Hall referred to is Act 250, which is Vermont’s land use and development law. It’s quite rigorous. But the people who live in these four towns weren’t going to rely on it, or leave anything to future generations. They took matters into their own hands — and they were the reason Hall changed his mind.

In early June, the Alliance for Vermont Communities held a big fundraiser: a semi-competitive bike ride through Tunbridge and Strafford. The ride started at the Tunbridge World's Fair grounds. Alex Buskey, the outreach manager for the Alliance, explained the origin of the ride’s name: The Ranger.

“A ranger is somebody that protects a specific plot of land. I want everyone here to leave as a ranger, not just for this place, but for everywhere you go ride, thinking about what it means to you, what it means to the people that live there,” Buskey said to a crowd of more than 200 cyclists.

Some people were just here to ride their bikes. But we talked to enough people who were clued in to the cause to get a sense of what motivated this opposition.

We caught up with Malachi Brennan at around mile 20 of the ride, on Monarch Hill Road — a steep dirt road that passes by hill farms.

“You have a guy with a vision, and he has good ideas behind his vision, but people with, you know, good ideas that believe really strongly in them can be really dangerous,” Brennan said while he pedaled. “And I think he needs to listen to the people who have lived here and lived here for a very long time.”

Brennan is a student at Vermont Law School, and said he’d done some volunteering for the Alliance.

“I’m just very wary of the guy and I wish he would appreciate the democratic spirit here, and listen to what the townspeople have to say,” he said.

Suspicion of David Hall, and a desire for local control.

Peter Anderson of the Sharon Planning Commission was volunteering at the event. He had a strong dose of the former.

“[Hall] has clearly predicated his wealth on mineral extraction, and that would be something that presumably they would be interested in doing,” Anderson said.

You might remember, from John Echeverria’s presentation, that the design of a NewVistas community has a section set aside for drilling. Anderson was concerned that that was a primary objective for David Hall.

“I don’t know really what’s under there. And I don’t know whether he does. But that’s what his business has been," Anderson said.

The most rattled person we met was probably Jane Huppee, of Tunbridge. Jane is a seventh-generation Vermonter and the treasurer of the Alliance. We left the bike ride to drive up to her house on Button Hill Road, where David Hall has purchased several parcels.

“People are not in favor of this, and they are in favor of saving our rural communities as they are today and can be in the future,” Huppee said, “with similar values and similar aspects of rural living.”

We sat on Huppee’s front deck, which has spectacular western views. And she talked about how unsettled she's been by the changes on her road.

“We’re not opposed to new people coming here. We welcome new people. But we don’t know who they are,” she said. “Not knowing who’s in the houses in our neighborhood, because [Hall] is renting — which is fine, he has that right. But it doesn’t lend to a cohesive neighborhood.”

Huppee talked about a sign that one of her new neighbors had put up at the head of their driveway. She had a photo of it on her phone. It’s one of those faux-official warning signs that you can buy. It says, “Due to an increase in the price of ammo, there will be no warning shot.” You could read it as a joke, but Jane Huppee didn’t.

“That’s not a very nice, neighborly sign to have out. It doesn’t give a nice warm feeling towards neighbors, and again, we don’t know who lives there,” she said. “So we don’t know what their intent is, or we don’t know what their character is, or anything about it.”

When asked whether she’d tried to introduce herself to the new neighbors, Huppee said she hadn’t yet.

“We don’t know when they’re here. They’re here off and on; they’re not here in the winter at all,” she said. “So we haven’t. But we should. Because that’s how we want to be as neighbors.”

We asked David Hall about the people he’s been renting to. Did he have a personal connection to any of them? He wrote back in an email, “All to locals.”

Back at the Tunbridge World’s Fair grounds, riders were returning to a big party, and the neighbors who did know one another were enjoying craft beer and cow pie bingo.

Out in the parking lot, Michael Sacca, the president of the Alliance for Vermont Communities, said he too was suspicious of Hall’s plans.

“We’re in it for the long haul,” he said. “And frankly, we don’t necessarily trust that it’s that far off.”

Sacca made clear that the Alliance isn’t ideologically opposed to growth. “Alliance for Vermont Communities, we are not against development. We are for appropriate-sized development,” he said. “Nowhere in our town plans, the regional plan or state guidelines does it say anything about building outside of the village settlements in this way."

And Sacca said that Hall buying so much land has injected some uncertainty into the real estate market: “We know of people who decided not to move here, for instance. And they decided, ‘Oh, you know, I think we’re gonna look somewhere else,’ because it just seemed like, ‘Why would we step into this morass?’”

The Alliance managed to work on two fronts: saying no to David Hall, while simultaneously building relationships across the four towns that hadn’t been there before.

“If there was one good thing that came of NewVistas being here,” said organizer Alex Buskey, “it was the cohesion among the four towns and the people that live here, all having one common goal that's really strong. So it brings out the most passionate people."

And those passionate people got results. In March of this year, John Echeverria, the guy whose presentation we heard earlier, testified in front of the Vermont House Committee on Natural Resources, Fish and Wildlife. Echeverria said Hall had broken Vermont and Utah nonprofit laws when he transferred his land from his nonprofit NewVistas Foundation to a for-profit LLC. In April, the Vermont House passed a resolution opposing NewVistas, saying the development would “undermine the historic character of these towns” and “degrade the area’s natural resources.” In early June, the Alliance announced that, with help from the Vermont Land Trust, it had purchased a 218-acre parcel just east of the Joseph Smith birthplace.

And then, just a few weeks later, the pièce de résistance: The National Trust for Historic Preservation put Royalton, Sharon, Strafford and Tunbridge on “watch status” in its 2018 list of “America’s Most Endangered Historic Places.” The Alliance had campaigned for the designation.

'I'm tired of the drama'

The day the list came out, David Hall decided to pull the plug on his plans for Vermont. We talked to him the next morning.

“I mean, that was a really good move on the part of those that opposed my land purchases there,” Hall said with a rueful laugh. “That was kind of like a last straw for me, about, ‘Gee-whiz, I don’t want to be on a national watch.’ So, I’m tired of the drama, and [will] move on.”

David Hall isn’t the first person to watch his dreams for a Plat of Zion community get crushed. Joseph Smith himself actually tried to establish his own utopian community back in the 1830s, on a piece of land in Missouri.

“He declares that this place is going to be Zion, or the center place of God’s restored kingdom,” says Benjamin Park, the religious history professor at Sam Houston State University.

It did not work out that way. The locals drove Smith out. And he didn’t have any better luck in the other places he tried to establish his Plat of Zion.

“Joseph Smith himself kind of moves away from that society because it fails quite spectacularly over the next couple years, both for internal and external reasons,” Park says.

Smith never really found a peaceful spot to land. In 1844, while he was being held in a jail in Illinois, an angry mob stormed the prison and killed him.

“It’s surprising how even the concept of somebody’s idea can arouse so much, you know, opposition,” David Hall says.

Hall doesn’t have to worry about a lynch mob, of course. And he doesn’t seem to hold a grudge with the opposition that ran him out of town in Vermont.

“There’s some people that have, you know, a firm dream of keeping things exactly like they are, and that is their dream, right? So it’s just a conflict of long-term dreams,” he says.

Hall says this isn’t the death of his NewVistas plan by any stretch. It’s just that Vermont won’t get to be a part of it.

“The sad part for me is I don’t think they realize the economic disaster and actually the ecological disaster that they’re on track [for],” he says. “The large rural sprawl systems that Vermont is currently promoting are number one, not sustainable at all when you actually analyze it. But also not socially and economically viable. You know, to be so spread out, and to have the huge high cost of the infrastructure. So only very wealthy people will be able to live there.”

Missed opportunity?

We got back in touch with our question-asker Jillian when news broke that Hall was abandoning his plans.

“It feels sort of like a little holiday! It feels really great,” Jillian said. “There’s a small part of me, though, that’s kind of like — I’m the type of person that feels really bad for the losing team at the Super Bowl, and I sort of feel that way a little bit for David Hall. Like, just the tiniest little bit. Because it seems like he really felt very pushed out, in an aggressive way. But it’s a great day for the four communities; it’s really great news.”

Jillian said she could see where Hall is coming from when he says Vermont’s trajectory isn’t sustainable.

“I don’t think that’s completely wrong,” she said. “I mean, there’s many times when I’m, you know, driving my car the 15 minutes it takes for me to go fill up on gas, or whatever, or just to go to the co-op. And, I’m like, ‘This is crazy.’”

Green technologies like electric cars are getting us closer to sustainability, Jillian says, but there’s still a long way to go.

“I feel like it's funny because [Hall’s] development plans were really counting on the advancement of a lot of technology. And … in that same vein, I think the success of rural Vermont is also sort of waiting on similar technology,” she said.

But not everyone is as sanguine as Jillian is.

“Well, look, I always think it’s tragic when an opportunity to develop and create jobs and create vitality and prosperity in a community goes away,” says Joan Goldstein, the commissioner of the Department of Economic Development within Vermont’s Agency of Commerce and Community Development.

Goldstein also sat on the Royalton Selectboard until 2017, when she decided not to run for re-election. She said she had trouble with her community’s response to Hall’s ideas.

“It felt at one point that people knew more about what they didn't want to happen rather than what they did want to happen,” Goldstein said. “And it really did feel like quite a shame that there's this lack of investment and interest at the same time people are upset about declining school populations and consolidation of schools and school closures.”

Commissioner Goldstein says she understands the critique that 20,000 people is too many for these four small towns. But she thinks Hall’s idea deserved a full review under Act 250:

“They study impacts on transportation, schools, ag land, you know, all of it. We have a very robust land-use regulation so I'm not quite sure why that was not going to be good enough to guide this particular project.”

And Goldstein says she’s worried about future developers, and how they’ll feel about bringing their ideas and money to Vermont.

“You know, what a terrible message to be sending people who want to invest in Vermont. We need growth in Vermont, we need people to come here, and now we have somebody who has got an idea that we don't really like, and so we decide to openly and actively oppose it without really giving it its share of due process,” she says. “So I thought that was rather prejudicial.”

Vermont Gov. Phil Scott had a similar take. The day after Hall announced his plans to sell his land, Scott said this at his weekly press conference:

“It’s interesting. We want to be so welcoming to everyone in Vermont. I think we have a high degree of tolerance as a state … And I was struck by the intolerance of some of the statements about not wanting them to be here. And I just thought that was unfortunate. We need more people in this state. Maybe not as many as Mr. Hall wanted right off the bat, but again, my message is: We’re welcoming, we want people here.”

Land on the market

Paul Bruhn says he would “caution anybody to get carried away with the idea that this was an effort that was based on intolerance.”

Bruhn, the executive director of the Preservation Trust of Vermont, says intolerance had nothing to do with it.

“It had to do with somebody coming into the state without having a discussion with people and imposing a development idea or scheme on Vermont before there was an opportunity to have a dialogue,” he said.

The Preservation Trust and several other groups — the Vermont Natural Resources Council, the Upper Valley Land Trust, the Vermont Land Trust — worked with the Alliance for Vermont Communities to try to stop David Hall.

But Bruhn says he never imagined they would be so successful. He says Hall’s about-face was “a complete surprise.”

“[It’s] sort of like the dog that actually got the car,” he joked.

Now, instead of opposing David Hall, at least some of these groups might end up giving him money, so they can buy back his land. Hall’s got over 1,500 acres to sell, for about $7 million.

“I don’t know that there will be the ability for the organizations to jump in and agree to acquire everything for the $7 million,” Bruhn said. “I don’t know whether that’s going to happen. I think it is probably a little unlikely.”

When Bruhn spoke with Brave Little State, he hadn’t even had a chance to meet with all the other groups yet. But he said he had had some very cordial conversations with David Hall about a potential sale.

“You know, he’s very interested in seeing as much of the property conserved as possible,” Bruhn said.

There’s also been talk of subdividing — to conserve the bulk of the acreage, but keep the homes on the housing market. But Bruhn said it’s still very early days.

“Oh, we’re at the very beginning,” he said. “This will all take a lot more conversation, among the conservation partners, as well as with David directly.”

David Hall also told us that he’s interested in conservation, too – though he added that he’s not in a rush, and that the market will determine where things go.

So until he sells, if he does ultimately sell, Hall will remain a major landowner in these four towns — and a landlord, and a taxpayer. But he seems to have made up his mind that he won’t be a developer.

Subscribe to Brave Little State for free, so you never miss an episode:

Loading...

Disclosure: NOFA-Vermont, one of the groups at the Alliance for Vermont Communities' Ranger fundraiser, is a sponsor of Brave Little State.

Brave Little State is a production of Vermont Public Radio, and is made possible by the VPR Innovation Fund. Editing this month by Lynne McCrea and Henry Epp. Our theme music is by Ty Gibbons, and we have engineering support from Chris Albertine. Special thanks to John Gregg and Rob Wolfe at the Valley News, BYU Radio in Provo, Utah, Meg Malone, Steve Zind and Bob Kinzel.