In this installment of our people-powered journalism show, we continue a Brave Little State tradition like no other. Each of the past three years, our show has released an episode investigating the origins of Vermont road names submitted and voted on by you, our listeners:

- A Brief History of Vermont Road Names (2018): States Prison Hollow Road, Poor Farm Road, Lime Kiln Road, Kelley Stand Road

- A(nother) Brief History of Vermont Road Names (2019): Mad Tom River Road, Hi-Lo Biddy Road, Star Pudding Farm Road, Sawnee Bean Road

- Brave Little State’s 3rd Annual Brief History Of Vermont Road Names (2020): Devil’s Washbowl, Popple Dungeon Road, Lost Nation Road, Smuggler’s Notch

In this episode, the team journeys to the back roads of Vermont yet again to learn about three mystifying road and place names: Cow Path 40 in Marlboro, Agony Hill Road in Reading, and Texas Falls in Hancock.

Note: Our show is produced for the ear. We recommend listening to the audio above if you can! But we also provide a written version of the episode below.

Subscribe to Brave Little State for free, and never miss an episode:

Loading...

Cow Path 40

Reported by Angela Evancie

Our first road name takes us to the southeast corner of the state, thanks to a question from listener Roo Grubis, of Guilford.

“I would very much like to know the origin of the name of Cow Path 40, in Marlboro,” Roo asked. “As far as I can tell, there are no Cow Paths 1-39. Thanks!”

Roo is correct. There are no other numbered cow paths in Marlboro. There is only Cow Path 40.

Cow Path 40 is a Class 3 dirt road, just over 2 miles long. Driving it takes you past some houses and long driveways that wind into the woods.

“And cars regularly go way faster than they should,” says Andrea McAuslan, a lifelong part-time resident of the road, who says the road was also referred to as "Billings Road" when she was growing up.

The beautiful thing about the origin of the name “Cow Path 40” is that basically, everybody’s memories of how it came to be seem to match.

[S]omebody stood up at Town Meeting one day and said, ‘That’s not a town highway, that’s a cow path.’”David Elliot, Marlboro Highway Department

“Cow Path 40 was really originally Town Highway 40,” says road foreman David Elliot, of the Marlboro Highway Department. “All the roads are done by Town Highway numbers, and that’s really where it came from. Years ago, you know, they said, that’s Town Highway 40, and I forgot who it was, but somebody stood up at Town Meeting one day and said, ‘That’s not a town highway, that’s a cow path.’”

Gretchen Becker, who lived briefly with her late mother Ellen on Cow Path 40, and who now lives the next town over, in Halifax, recalls that it was a popular nickname among Marlboro’s road crew.

“Jim Herrick Sr., who is now deceased, worked on the road crew, and he and his fellow members used to call it ‘Cow Path 40’ because it was in such bad shape,” she says.

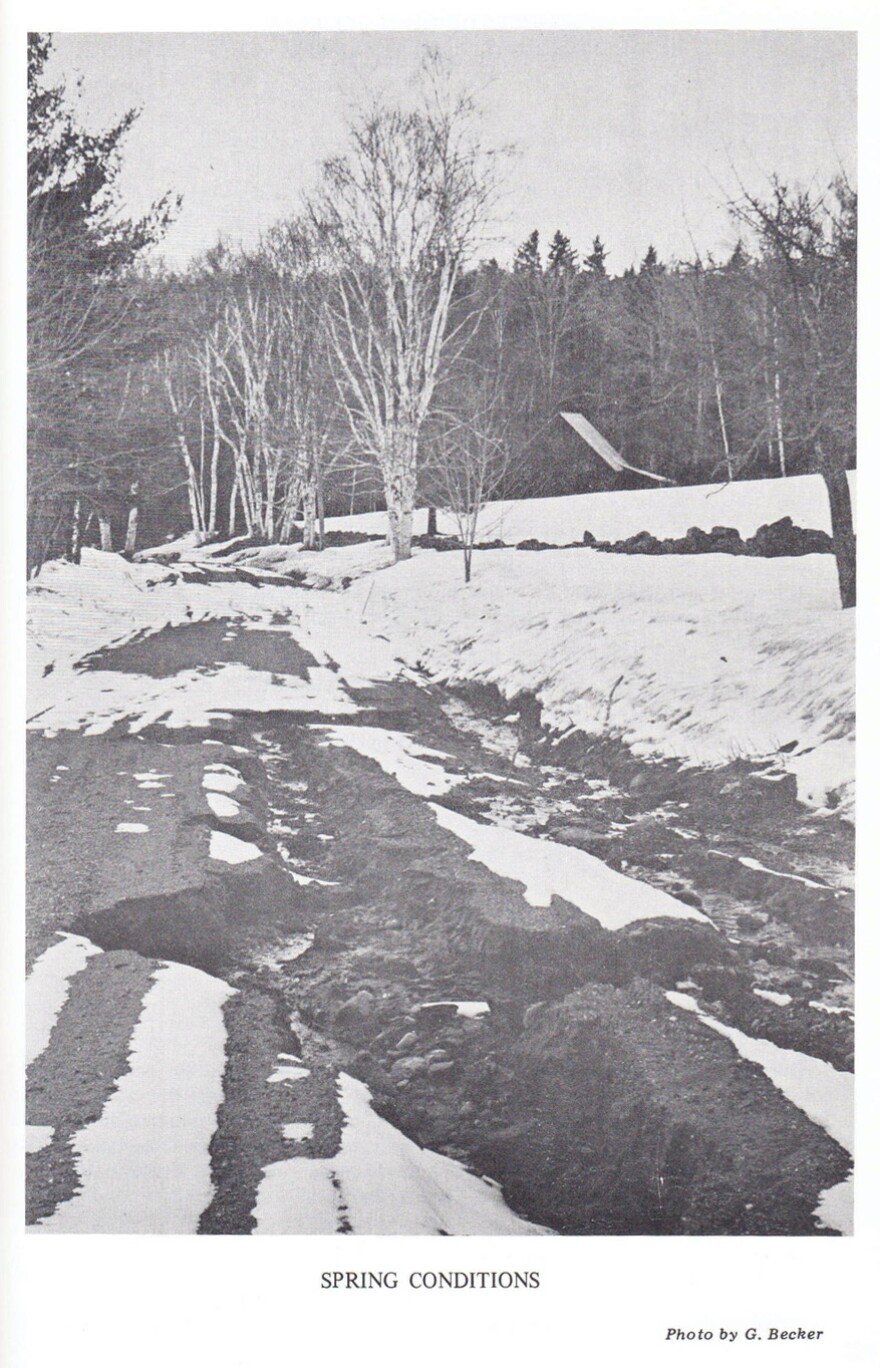

Marlboro Town Clerk Forrest Holzapfel, who grew up here, has a similar recollection: “When I was a little kid I remember it being extremely narrow and it was entirely impassable in mud season.”

When I visit his office, Holzapfel shows me an Agency of Transportation map of the town of Marlboro indicating that the small community does indeed assign each of its roads a “town highway” number. That count actually goes up to Town Highway 49.

So: Cow Path, because it used to resemble one, and 40, because it is technically “Town Highway” 40 — with this interpretation of a “highway” being very generous. (“Highway 47 is .12 miles,” Holzapfel points out on the map. “Couple a hundred feet long, and that’s that.”)

Gretchen Becker’s mother Ellen was the one to help make the name official.

“She took a petition around to all the neighbors to see if they would mind if it was called that, and they all agreed,” she recalls.

This was in the 1980s, maybe earlier. Andrea McAuslan remembers the petition.

“Everybody wrote back and said, absolutely. Go for it. Because we thought it was so charming,” she says.

And even though the road was never a dedicated cow path, there were cows on it in previous decades. They too were part-time residents.

“They used to keep cows across the road from my mother’s house,” Gretchen Becker says. “Some people from West Brattleboro used to bring cows up in the summer.”

“They would sometimes get out, and there literally would be cows on the road,” Andrea McAuslan says. “So that was always fun.”

Like many of the eccentric road names we’ve explored in years past, the sign for Cow Path 40 has disappeared more than once.

“The more you put oddball names to stuff, more people like to steal your signs,” laments road foreman David Elliot. “So that’s one of our signs that are harder and harder to keep.”

At one point, Town Clerk Forrest Holzapfel says, the road crew strung barbed wire around the pole, as a deterrent. “[But] each time the thieves made off with it.”

“I have to admit, you know, I might have been tempted myself,” Andrea McAuslan says. “But I never took one.”

Eventually the town started putting C.P. 40 on the sign, to make it less enticing. That worked — for a while.

“Actually, I just found out today that there’s a person that lives on that road at the end that has the same initials,” David Elliot tells me. “And so now I’ve got a better idea where our signs might be going. But you wouldn’t think they’d need too many.”

On the day I visit, there is no Cow Path 40 sign at the intersection of Ames Hill Road. Though there is a little free library, tucked into the trees.

I drive up to Andrea McAuslan’s house, which used to have a long-range view, before some trees grew in. She gives me a little tour of the road, and tells me about how it’s changed.

“I would say it was only recently that the population got down to less than 50% being people who have known each other for at least three if not four or five generations,” she says.

These days, neighbors might not maintain their relationships the way they used to, but the town certainly takes better care of the road. Meaning it’s more like a road, and less like a cow path. In mud season, David Elliot says his crew gets to it — eventually.

“Sometimes that gets left a little longer, the mud seems to get a little deeper, or they [residents] feel it does, before stuff gets done,” he says. “But I don’t know if it’s any worse than some of our other roads. They’re all bad in mud season if you have to drive ‘em.”

So while it does have a cool name, Cow Path 40 could basically be any Vermont road. It’s dirt. Hilly. Mostly wooded, with some views. At one point it had cows on it, but not anymore. And the residents? Well, there are some old-timers and some newcomers.

Does this make it … a boring road?

“It’s not boring, it’s very pretty,” Gretchen Becker says.

And though the road’s more longtime residents might disagree, Becker assesses the road thus: “Unfortunately other than the name, it’s nothing special.”

_

Agony Hill Road

Reported by Myra Flynn

“We moved onto this property in 1977. We bought the place in ‘79. You can do the math.”

That’s Gardner Smith. We speak on Zoom, and eventually in person. And yes — I did do the math. Though Gardner was born and raised in Windsor County, for the past 42 years he has remained in one house at the start of one very curiously named road in Reading.

“My curiosity was piqued by a client’s query about the origin of Agony Hill Road,” Gardner explains. “And I have no idea. I mean, a lot of people ask me, and I usually tell them, `It's straight up and straight down.’”

Reading is a southern Vermont town off of Route 106. Gardner tells me if I visit, I should not use a GPS, because Agony Hill is too sequestered and confusing a road for Siri to navigate. I’d be lying if I said that his warning didn’t make me wanna go more. So, in early August, I packed my mud boots and bug spray and started my drive towards a pretty cool adventure.

Also, I may have used my GPS. I wanted to see what would happen.

Reading is about 10 miles south of Woodstock, and as soon as I hop on Route 106 I pass the Green Mountain Horse Association (GMHA). Unbeknownst to me at the time, horses will play an important role in my investigation.

Eventually, I get to Reading, and see the sign for Agony Hill Road, where our question-asker Gardner lives. He’s been waiting for me with his entire family, and I’m greeted with a giant hug from his granddaughter.

I quickly learn that Gardner is one of those retired folks who refuses to retire. He’s a farrier. In fact, Gardner had just finished putting some shoes on some horses before my arrival. He jokes that he helps to put on their brakes or their studded snow tires, and he also tells me that over the years, his job has kept him pretty busy. As I continue my investigation into Agony Hill Road, I begin to understand why.

Reading, and its surrounding towns, all have a rich history of horses in common. Gardner’s wife, Cathee, is pretty sure this has something to do with the name of the road.

“People say to you, ‘Do you really live on Agony Hill?’ And you have to say, ‘Yes.’ ‘Well, why is it called Agony Hill?’ And the only thing I've ever known is that on the three-day 100-miler, the horses went up Agony Hill. I assume that's how it got its name.”

From what I can tell, Cathee’s right. More on the epic three-day, 100-mile horse ride later.

I tell Gardner I’m happy to follow his truck up Agony Hill so I can see it for myself. He laughs and tells me that’s impossible — my car won’t make it. So, after we both confirm that we are vaccinated, I hop in his truck and away we go.

One thing to know about Agony Hill Road is that it switches its name three times, all without taking a single turn. It’s only technically “Agony Hill” for about a half mile, and then it becomes Keyes Mountain Road … and then Malagash Road.

On some maps it just stops being named anything. As I learn riding along with Gardner, that’s because the road stops too. At a certain point, we are driving through the woods. And Gardner’s right, my car definitely wouldn’t have made it.

“Oh Lord is this bumpy,” I exclaim while driving over a particularly large boulder in the middle of Agony Hill Road.

“This is all sheep pasture,”Gardner says. “I'm gonna make an attempt to get out to the very end of the bad section.”

Gardner keeps referring to the “bad part” of the road on our drive. Honestly, I thought we’d reached it about five times before we did.

A self-evident answer to the origin of the road name is that this is an agonizingly steep hill, which I would deem less of a hill, more of a 90-degree angle. We are in the woods, and Agony Hill has turned from dirt road to deep and muddy trenches, boulder-sized rocks, fallen trees and even a light waterfall running through the center.

We drive through it all.

Gardner recalls first hearing the name Agony Hill Road when he was a teenager, when he was riding in the event widely known around here as the three-day 100-mile ride. It’s organized by the Green Mountain Horse Association and dates to at least 1936. It’s a rigorous and competitive sojourn that tests the will of both the rider and the horse.

I spoke with the GMHA, and though they don’t quite know where the name Agony Hill originated, they did confirm that about halfway into the 100-mile ride, horses and riders often hit their limit, where they have to decide if they are going to work through it, risking the well-being of both human and horse, or turn around and go home.

Historically, Agony Hill Road was about that halfway point.

I reached out to Marjorie Strong, Assistant Librarian at The Vermont Historical Society, to learn more of the history behind the ride.

“Well, like all history, this is speculation,” Marjorie admits. “But it's pretty good [speculation], actually.”

Marjorie found an interesting tidbit about Agony Hill Road in an old article from the Rutland Herald.

“I love newspapers,” she says. “It popped up in 1970, in a story about the Green Mountain Horse Association’s 100-mile trail route ride.”

Marjorie continues: “First of all, it was a terrible ride. It had awful weather, lots of horses dropping out, and then it has this paragraph saying, ‘Another 10 or 12 animals were taken out of the 100-mile event during the trail ride Friday.’ Most of them seemed to be dropping out at about the time the trail took them up, quote, ‘Agony Hill,’ or another, quote, ‘Heartbreak Hill’ in the Reading and Hammondsville areas.”

Heartbreak and Agony. Who knew Reading was so poetic?

Rides like the three-day 100-miler used to be run to test the horses’ mettle for the military. The goal was to see if the horses would be good cavalry mounts. Then, after World War I, as cavalry transitioned over into tanks, most of these trials stopped.

But the GMHA, which has been around since 1926, still runs them today. In fact, they’ve only missed a single year due to Tropical Storm Irene.

“And, I mean, what's interesting about the articles,” Marjorie adds, “is that these horses were pulled before the hill. The riders looked at it and said, ‘This isn't gonna work. My horse isn't going to make it.’ So they pulled [out] knowing that they weren't going to injure the horses, that the win wasn't [the most] important to them. So, I think it's nice sportsmanship. And also it's a kind of shipwreck of your hopes. You hope to win the GMHA this year but, nope, Agony Hill gotcha.”

Gardner Smith remembers his own gotcha moment.

“I can remember getting to the top of the steep area. And there were several of us taking a break with the horses. As a typical 16-year-old, I said, ‘Haha, this is heartbreak and agony.’ And then a droll voice over my shoulder said, ‘No son. This is just agony.’”

The GMHA told me they haven’t used Agony Hill Road since well before 1995. After many decades of sending horses up the hill, the course has been rerouted.

_

Texas Falls

Reported by Josh Crane

Our last story focuses on a place name, rather than a road name, thanks to Zoe Pike of Ripton.

About nine years ago, Zoe moved to Vermont with her partner and two young kids. Shortly after they arrived, their neighbors invited them on a day trip to Texas Falls.

“It was perfect for my kids at that age. They were able to do the little hike. They thought the waterfalls were amazing and beautiful,” Zoe says. “And they actually asked, ‘Why do you think it's called Texas Falls?’”

That question sparked Zoe’s curiosity. But she was never able to find the answer, and it gnawed at her for years. Then, a few months ago, she submitted it to Brave Little State:

“What is the origin of the name of Texas Falls in Hancock?”

Texas Falls is a popular destination in the Green Mountain National Forest. It’s located off Route 125 between Hancock and Ripton. It’s a cascading waterfall that rushes dramatically through a narrow gorge. And it’s just steps from a parking lot.

There’s no swimming allowed, but it’s the type of place where people like to go and spend an afternoon, walking the short nature trail and hanging out at the picnic tables. But it’s also akin to a glorified rest stop for people driving over the Middlebury Gap who get enticed by the sign for some place known as “Texas Falls.”

I visited the Falls on a beautiful summer day to crowdsource information about the name. I talked to tourists from all over the country, and everyone I met shared Zoe Pike’s curiosity, including Alli Patalik from Connecticut.

“Because, I wonder, what does Texas have to do with any of this in Vermont?” Alli asks.

Meanwhile, Jazmin Derby from Florida has been visiting Texas Falls for 20 years. “It's always confusing when we tell people that we're going to Texas Falls, but it's in Vermont,” she says.

Vermonters seem just as perplexed as tourists. Bill Lawlor of Norwich often goes hiking in the area and knows the Falls really well. But Texas? “I don't see any particular connection. I mean, truly.”

I made more calls than I care to admit for this story: town clerks, librarians, historians, U.S. Forest Service archaeologists. And, eventually, Bruce Flewelling, a retired assistant ranger out of Rochester, who managed the Texas Falls area for decades. Surely he knows where this name comes from, right?

“No. The answer is no,” Bruce admits. “I wish I had a clue. From the day I got to Rochester [I was wondering], you know, how come it’s named Texas Falls? The district ranger, the locals... they didn’t know. It's always been Texas Falls!”

This isn’t the first time VPR has explored this topic, either. In 2003, author and English professor Alan Boye wrote an essay about Texas Falls.

“No one can explain how the name Texas came to be associated with this small place so deep in the Green Mountains,” Alan wrote.

After visiting Texas Falls, I stopped by the ranger station in Rochester. I thought I may have cracked the mystery when they told me that their office had looked into the origin of the name in recent years.

They said they were getting so many questions that they wanted to erect an informational sign on location with an explanation. But their own search proved futile and, in lieu of a sign about the name, they instead put up a sign detailing the geological history of Texas Falls. No mention of the origin of the name.

Apparently, it’s easier to document the geological history of Texas Falls from tens of thousands of years ago than it is to remember why, a couple hundred years ago, someone named a small-to-medium sized waterfall in the middle of Vermont… “Texas.”

To be fair, the geological history is pretty unique. The foundation of Texas Falls is something called a glacial pothole, which is pretty much exactly what it sounds like: a large, cylindrical hole carved by glaciers.

So, I end my investigation into the origin of the name Texas Falls without a solid answer. That said, I did stumble upon a number of theories. Four of them, to be precise.

Theory One: It’s a joke! This seems to be the most popular theory. Texas is big. Vermont is small. Texas Falls is small too, as far as waterfalls go. Author Alan Boye referenced this theory in his 2003 essay for VPR:

“Somebody was laughing at the very idea of anything Texas sized in tiny Vermont.”

Theory Two: It’s a show of rebellious solidarity. Vermont and Texas were both independent republics before joining the union, Vermont from 1777 to 1791 and Texas from 1836 to 1846.

Here’s Alan Boye again:

“The name dates to at least 1850 where it appears on old maps of the area. It might have been named to commemorate the short lived Republic of Texas.”

I followed up with Alan to learn more about this theory, and he offered some compelling historical context.

“The sequence was: Texas fighting Mexico, [Texas] becoming their own Republic, then joining the United States, and then the United States started the Mexican-American War,” he said.. “And there was a lot of rah-rah spirit in support of the United States in the Mexican-American War … So it could be that rah-rah America meant rah-rah Texas, because [Texas] was brave enough to stand up to Mexico.”

Alan also explained that the name “Texas Falls” started showing up on maps around 1850, a few years after the end of the Mexican-American war, lending further credence to the theory.

Theory Three: It’s named after a war general. This theory connects to Theory Two as well as a nearby waterfall, of whose name we do know the origins.

The Falls of Lana in Salisbury were named for Army General John Wool, who fought in the Mexican-American War out of Texas. Wool was an accomplished military commander and, during a visit to Vermont in 1848, the Falls of Lana were named in his honor — Llana is the Spanish word for “wool,” though the first “L” was dropped.

But what if John Wool actually had two waterfalls named after him on that visit, not just one?

Credit to retired United States Forest Service archaeologist David Lacy for putting forward this theory.

Theory Four: It comes from an Abenaki name. While “Texas” isn’t specifically an Abenaki word, more than one person I spoke to for this story suggested it may be a derivation. I contacted Abenaki scholar and linguist Jesse Bruchac to ask about possible connections.

“I thought on it, and would guess it may come from Taksus, an Abenaki family name,” Jesse wrote in an email.

Taksus … Texas … there might be something there, though it’s hard to know for sure.

So, take your pick: the name is a joke, it’s a show of solidarity, it’s named after a war general, or it comes from an Abenaki word. There’s your Texas-sized buffet of Texas Falls theories.

Loading...

Credits

Josh Crane, Myra Flynn and Angela Evancie reported this episode. Mix and sound design by Myra Flynn, with engineering support from Peter Engisch. Digital production by Josh Crane. Ty Gibbons composed our theme music; other music by Blue Dot Sessions and Myra Flynn.

Special thanks to Jonathan Connor, Charles Billings, Jeanette Bair, Holly Knox, Jesse Bruchac, Amy and Carolyn Crump, Shaun Bullens, Diane and Steve Frank, Brendan Hobson, the Davis Family Library at Middlebury College, and the Rochester Historical Society. Thanks also to Abagael Giles and Lesli Blount, whose copies of Esther Munroe Swift’s book, Vermont Place Names, were very helpful in our research.

As always, our journalism is better when you’re a part of it:

- Ask a question about Vermont

- Sign up for the BLS newsletter

- Say hi on Twitter, Instagram and reddit @bravestatevt

- Drop us an email: hello@bravelittlestate.org

- Make a gift to support people-powered journalism

- Tell your friends about the show!

Brave Little State is a production of Vermont Public Radio.

Clarification 9/16/2021: This post has been updated to reflect the fact that Andrea McAuslan remembers Town Highway 40 being called "Billings Road" before it earned its current moniker, Cow Path 40.