On Feb. 5, 1972, David Zlowe was traveling to Vermont on a ski trip with his family and a friend. The Zlowes were flying up from their home in Irvington, New York.

David's father, Leonard, was a salesman and an amateur pilot who liked to fly his family on ski getaways. His wife, Iris, had stayed home that February weekend, but 9-year-old David and the rest of the family were headed to Killington.

"My brother Roger was very much the athlete of the family," David explained. "He was eight years older than me, and in 1972 he was 17 and in most sports in high school. He was planning to go to the University of Colorado so that he could focus on skiing."

"My sister Randy was a popular cheerleader, and smart," David went on. "She was six years older than me and taught me the multiplication tables."

"I was the baby of the family," David said. "And our family loved to ski."

On this trip, his sister had brought a friend along. The girls were sitting in the backseat of the plane with David when they made an unexpected stop.

“There was, I guess, disorienting snow and the National Transportation Safety Board noted that my father was relatively inexperienced flying in those conditions," David said. "And we clipped the top of the trees at Mount Tabor and crashed.”

The small, twin-engine plane went down in a remote stretch of the Green Mountains about 20 miles south of Rutland.

David’s father and brother, who were in the front seats, died at the scene. But David, his 15-year-old sister Randy and her friend Pamela Fletcher huddled together that first night dressed only in what they were wearing on the plane.

They'd brought winter clothing along, but couldn't get to it because of the crash. Temperatures were below zero and David said he remembers the cold and smell of gasoline.

“We did hear some planes," David continued, "which apparently was the Civil Air Patrol looking for us. We didn't know whether they had found us or not. Unfortunately, the electronics in the plane weren't working anymore. Not even lights. So there was no way for us to communicate, and there was no way to get warm, so the only option was try to go for help.”

David said they saw lights in a distant valley and the next day worked their way downhill through deep snow until they came to an icy cliff.

He said they couldn't find a way around it and hung onto branches to slide and crash their way down.

“I went first; my sister was suffering the effects of exposure and was confused," David said. "And so I went on to try to get some help. And she had to stay at the top of the cliff.”

David said when he reached the bottom, the snow came up to his chest and it was hard to move.

“Ironically, the snow was warmer than the air. But by that point, I had lost feeling in my hands and legs and so went on a bit further and then collapsed in the snow," he said.

Pamela Fletcher was able to keep going. A news report in the Barre Times Argus said the 16-year-old eventually made it to Route 7, where she ran into tourists who came to her aid and took her to a nearby house. Rescuers then retraced her steps and found David.

He remembers hearing voices and a distant roar.

“And apparently it was a rescue team that came up on snowmobiles," David said. "In fact, they had sent two snowmobiles, and the terrain was so difficult that one of them turned over. So they had to send another rescue team to rescue the rescue team."

"One group found me and they determined that I was alive — not very alive, but alive," he said. "And so they bundled me up and took me down the mountain."

David said they followed his footsteps back until they found his sister where he had left her. But by the time they reached her, she had died of exposure.

The two survivors were taken to the hospital in Rutland. Newspaper reports described Fletcher’s condition as stable.

Her account of what happened appeared a week after the crash in the New York Daily News. VPR wasn't able to track her down for an interview, and David didn’t want to speak on her behalf.

The two have not kept in touch. David said Fletcher’s family filed a lawsuit after the crash which he said his father's employer handled.

This is David’s story, his memories of what happened in Vermont 50 years ago and the ripple effects of his injuries.

David’s legs were so severely frostbitten they had to be amputated below the knee, and he lost some of the use of his right hand.

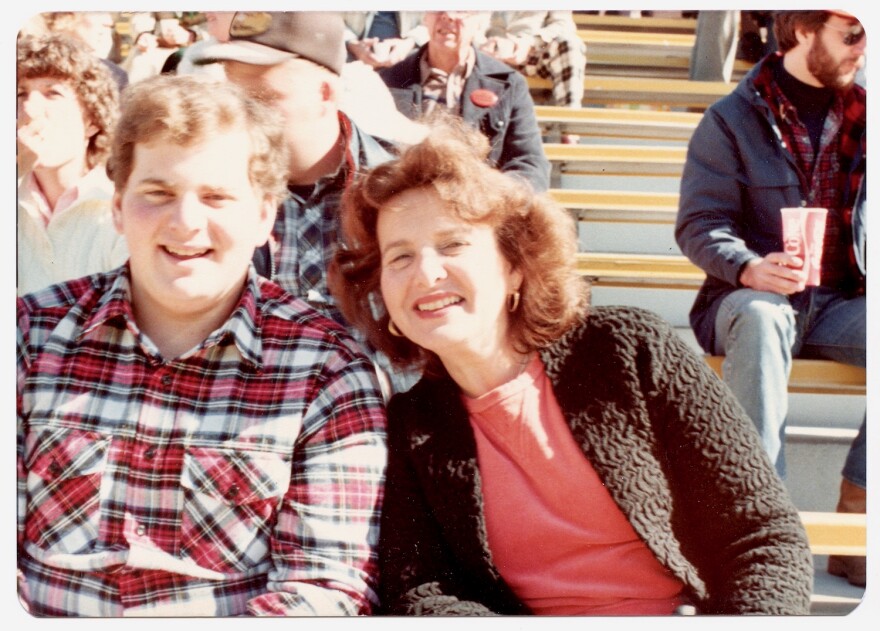

“It would be easy, I think, to dwell on what I lost," he said. "Obviously, I lost my legs. I lost my family. My mother died when I was 24 from cancer.”

David said he's spent a lot of time processing all of it.

“And over the decades, I've come to understand that it wasn't so much a question of what I've lost, as what I've had," he said.

"There are a lot of people who never have a brother and sister. I had a great brother and a great sister. My father, the same. And my mother I had for 24 years and the last words that she and I exchanged were 'I love you.' I would actually suggest that I’ve had a pretty good life.

"I was very fortunate to have a loving family. I didn't have them for as long as I would have liked. But maybe that isn't the most important point. Maybe the important point is the kindness and love that I received — that I was able to start learning how to share with others because of them.”

Today, David works for the Veterans Administration helping organizations work more effectively with people in need. It’s a career he loves.

Yet one thing has always bothered him. David said several months after the crash, his uncle sent a letter to the Rutland Herald on the family’s behalf thanking the community members who had rescued and cared for him.

"My mother asked me at the time if there was anything I wanted to say in the note, and what can you say? And certainly, what can a 9-year-old think to say? And so I was silent," he said.

Fifty years later, David wanted to finally speak up and thank Rutland for his rescue and care.

“In fact, that's been, I think, a lesson for me, throughout the remainder of my life. There are people who do amazing things to help other folks, folks they don't know," David said.

"On the surface, certainly this kind of thing that happened to me is very rare. But I like to think that we're rescued by strangers all the time, in much smaller ways. And, to me, that's sort of a wonder of existence. And I wanted to make sure that I acknowledge that and thank the people who were involved.”

David did one other thing he’d been putting off. He said on Feb. 5, he skied for the first time in 50 years, turning a day that has always been sad into something joyful.