In a new memoir, journalist Elizabeth Wilcox tells both her own story, and her mother's, by recounting the neglectful and isolating experiences her mother endured when separated from her family during World War II. In telling that story, the Fairlee author revisits decades of dialogue with her mother about her undiagnosed PTSD, and the transformation that came from understanding her own trauma.

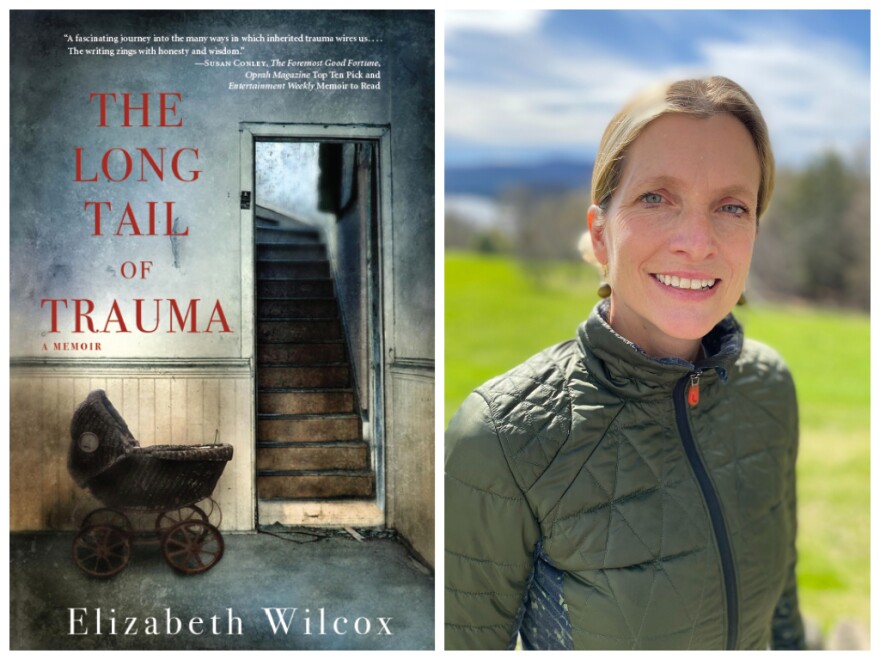

VPR’s Mitch Wertlieb spoke with Fairlee author Elizabeth Wilcox, a journalist who's worked in England, Hong Kong and the U.S., about her new book The Long Tale of Trauma: A Memoir. Their conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Mitch Wertlieb: You write in the foreword that early childhood is the foundational period on which mental health is built, and that adolescence is the time when adjustments and repairs can be made. Then you write that your mother had both of those windows shut on her.

Now, I know it's a complex tale and you can't tell it all here, but can you give us a kind of summation of what happened to your mother that shut those critical windows?

Elizabeth Wilcox: Yes. My mother was born on the eve of the Second World War in Germany. Her family — she was 3 years old at the time, and her younger brother was a year and a half — and they ended up having to flee Germany, and they moved to London. And then my grandfather was told to relocate to Holland.

Hitler invaded while they were there, and through various circumstances, my grandfather and my mother — aged 3, and her younger brother, aged a year and a half — managed to escape Holland. But my grandmother was left behind. And they arrived back into London, and at the time, there was something taking place called Operation Pied Piper. The government said, “children are not safe in London, they have to be sent out of London.”

So these children were sent out on these trains outside of London on their own. And there's actually a lot of literature around then. And if you look at Paddington Bear, you know, that image of a bear with a number around its neck, was basically these children. So my mother was sent out of London with her younger brother, and they went out and were picked up by these strangers. And my mother ended up being taken into an abusive home with her younger brother.

More from NPR: London Evacuees Bore A Painful Cost Of War [August 2014]

There was neglect, and lack of love, and lack of caring. And then eventually my grandmother was repatriated, toward the end of the war, and when she saw my grandmother, she couldn't accept her as her mother. And ended up spending her whole childhood in this succession of boarding schools. And by the time she got to adolescence, she had no relationship with her mother. She wasn't given the opportunity to attach. It was a very traumatic and difficult childhood for my mother, and it wasn't a childhood that looked like a childhood that many of us — and me, myself, got to experience.

All of this led you to delve into some research on [post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD], and you say there's a strong case to be made that genetics actually play a role in passing along that condition. What did you find in that research?

There was a study done on rats, where they put a mother rat through trauma. They withheld food from her, and she started hoarding. And then they looked at those female pups, and they saw that they had those same behaviors that their mother showed. And yet they hadn't experienced that trauma. So what they've discovered is that experience, or a traumatic event, can alter the expression of genes. This trauma turns on the gene, and then that trait can be passed on to the child.

Like any mother-daughter relationship, the one you have with your own mother is complex. And you don't shy away in this book from revealing your own thoughts — sometimes, exasperated thoughts — with your mother's mood swings. And she could be very cutting at times. I'm thinking about the sections of the book where she chides you for speaking too much “like an American” [for] saying things like, “yeah” and “you know” to start a sentence.

"I think there is something therapeutic in writing and in being reflective. We have to understand that the people we love, and the people around us who have suffered trauma, they are not the trauma. The effects of that trauma are a mask, and we have to access their core self." — Elizabeth Wilcox, author

I'm wondering if writing about your years, especially caring for your mother, served as a kind of therapeutic exercise for you, or is that just too simplistic a reading?

I think there is something therapeutic in writing and in being reflective. We have to understand that the people we love, and the people around us who have suffered trauma, they are not the trauma. The effects of that trauma are a mask, and we have to access their core self.

You indicate near the end of the book that your mother has come to recognize her own PTSD. Did she always accept that kind of diagnosis, or is it something that only occurred to her over time?

Basically she waving her hand saying, “I'm depressed,” but she wasn't using that language. She also actually, literally, lost her voice. She could not talk. She eventually found her way to the [National Institutes of Health]. And the NIH said, you know what, actually, you've got something called PTSD, which is not uncommon for people like you, who as very young children experienced this trauma during the Second World War.

And so for her, that was actually quite liberating, because she no longer thought, “Oh, I'm just complaining about nothing.” So she actually really believes quite strongly in talking about PTSD and talking about these issues.

That's remarkable. She regained her voice, I'm assuming?

Yes, it was transformative! When she got that diagnosis, she started to go to therapy, and she started to work through some of these challenges that she faced as a result of these early childhood experiences. It was very just validating for her.

I'd love for you to read a passage from the book, near the end, that sort of speaks to a kind of summation of why you wanted to tell these stories about your mother.

“I will come to see in my mother both courage and strength. I will see that she has never been afraid to have her nakedness exposed. I will recognize that while she has always wanted me to listen to her stories, she also has given them to me to write, despite how she might be perceived. For she always has believed in their power and her strength as a mother. I was given these stories, and so much else, from her.”

In the book's dedication page, you actually write that this book "is in memory of my father, who asked for my mother that this story be told." Why did he ask you to tell your mother's story?

I think he recognized that these experiences that my mother carried had long-term, lifelong effects on her, and something that actually is worthwhile sharing. I worked on this book for many, many years, but it wasn't until I saw children being separated from their parents along the border that I felt like this story really needed to be told. And my mother believed the same. When she sees that happening to children, she has felt and lived the impact of those types of experiences.

So in that passage I just read, I spoke about courage. It took so much courage for her to share this. It's very raw. It's very revealing. But in the end, both she — and, I think, my father — believed that it was a story that needed to be told.

Have questions, comments or tips? Send us a message or tweet Morning Edition host Mitch Wertlieb @mwertlieb.

We've closed our comments. Read about ways to get in touch here.