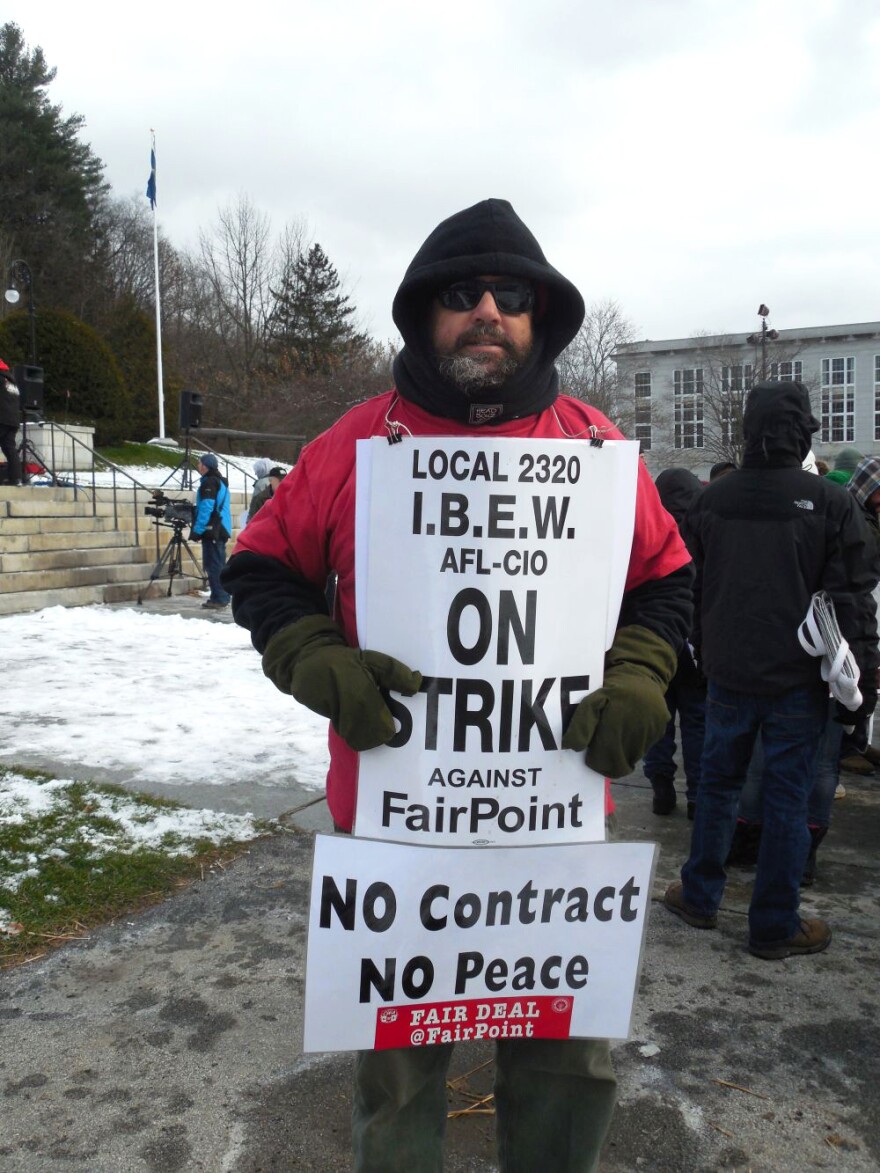

As the strike by FairPoint’s unionized employees nears the two month mark there’s still no sign of progress toward an agreement between the company and workers.

In deciding to strike the unions felt they had no choice, but it’s an option that has become rare and not nearly as effective as in the past.

According to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2013 there were 15 labor stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers.

That’s a dramatic decline from the hundreds of strikes that occurred every year from the 1950s through the 1970s.

“In many analysts' minds the strikes disappear as a relevant labor relations tactic,” says Bob Bruno, professor of labor and employment relations at the University of Illinois. Bruno says when roughly one third of U.S. workers were members, unions had more leverage.

Today, with private sector union membership at about 6 percent, the balance of power has shifted in favor of the employer – who can hold out and ultimately do away with union jobs.

“An employer cannot fire a worker who is striking legally, but they can permanently replace them," says Bruno. "There is a distinction under the law. So that makes it very risky to strike in the United States. The law is simply not protective of workers,”

He says President Ronald Reagan’s firing of air traffic controllers in 1981 may have been a turning point for when private employers began replacing union workers rather than reaching an agreement with them.

"An employer cannot fire a worker who is striking legally, but they can permanently replace them. There is a distinction under the law. So that makes it very risky to strike in the United States. The law is simply not protective of workers." - Bob Bruno, professor of labor and employment relations at the University of Illinois

Bruno says it’s much more difficult for unions to prevail if they can’t shut down a business.

Since the strike began in October, FairPoint has been using replacement workers to fill the jobs of union employees, although the company says it is still ready to negotiate with the unions.

The fact that this is a different era than in past strikes is not lost on FairPoint’s unions. Although members had authorized a strike, none was called when the contract expired in early August. Workers stayed on the job a few weeks later when FairPoint declared an impasse and unilaterally imposed the terms of its contract offer.

"Companies are much more willing to take the pain of a strike realizing that they're in a much stronger position that they have been before." - Marick Masters, director of Labor@Wayne

But by mid-October, with no progress in negotiations and no talks scheduled, the unions decided they had no choice.

Marick Masters, director of Labor@Wayne, which includes the labor studies program at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, says the stalemate is much harder for the union to maintain – with workers lacking health care coverage and living off part time jobs. “Companies are much more willing to take the pain of a strike realizing that they’re in a much stronger position that they have been before,” says Masters.

Since the strike, the workers and FairPoint have waged a public relations battle.

Masters says public opinion sometimes helps striking workers by creating pressure on an employer to settle, but he says public opinion is rarely uniform. The state can’t demand a resolution to the strike, but it can demand action on the service problems customers have been experiencing since the strike began, which could in turn pressure FairPoint to bring back the union workers.

“I think the company has to be mindful of that. The company also has to be mindful of what its investors want,” says Masters.

The recent history of labor negotiations is not favorable for unions. “Essentially they have been in a protective, defensive mode for decades. You get a lot of concessionary bargaining,” says Bruno.

But first the two parties will have to start bargaining again.

FairPoint has insisted that the union must meet its demands, including that employees take on some of the cost of health insurance, eliminating health coverage for future retirees, moving from a defined benefit retirement plan to a 401K plan, and allowing the company more flexibility to hire non-union contract workers.

The union says it has made proposals that would reduce FairPoint's health insurance costs by $200 million, but it says can go no further.