More than a hundred schools across Vermont are trying a new way to keep kids from being disruptive. It’s called PBIS—short for “Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support.”

It's getting noteworthy results, for example, in Hartford. That's where Dothan Brooks Elementary School got a gold star from the state’s Agency of Education for changing the way students behave by handing out fake money.

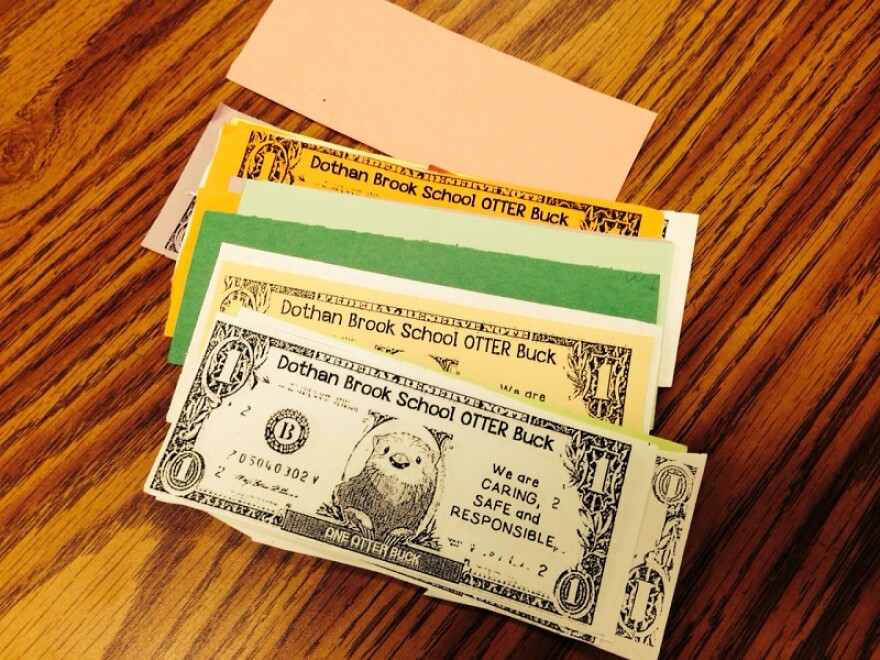

It’s called “otter bucks,” because the school mascot is an otter.

“It looks like a dollar bill with an otter where the President’s head belongs and kids earn those for caring, safe and responsible behaviors. Our expectations — we don’t use the word rules, we use expectations — are that everyone here, adults and children, are caring, safe and responsible,” said school guidance counselor Rebecca Lallier.

Otter bucks can be either be pooled by a whole classroom for an extra recess, or redeemed personally, for a free book, for example.

To learn more about how to get them, we visited a third grade classroom.

Kids in a circle paused their lively but respectful science discussion to tell us how well they’ve been behaving lately.

“I had an otter buck because I was focused on reading," said one.

“I got my otter buck for being caring in art by being quiet,” another piped up.

And “My name is Jack and I got otter buck for cleaning up fast without talking in art.”

From an excited little girl: “I got my otter buck for being the first table to be quiet in art. Is this thing even working?”

That last question was directed at our microphone. These kids seemed both curious and polite. Since the school has started handing out otter bucks, their principal, Rick Dustin-Eichler, says classes are running much more smoothly, without many behavior problems. Of course, some students still do act out. But Dustin-Eichler says with daily, detailed PBIS reports, teachers and parents figure out together what’s behind the bad behavior, so they can reinforce better choices at home as well as at school. And that, he says, is a vast improvement on the bad old days of his youth.

“I remember standing against the wall at recess, which was the big thing, and … it wasn’t seen as this teachable moment. One of the big tenets of PBIS is that students want to fit in,” said Dustin-Eichler.

What prevents them from fitting in, he adds, is that they don’t know what is expected of them. He says PBIS works best when acceptable behaviors are very specifically taught before the rewards start appearing. Eventually he says, kids become less dependent on the handouts.

This school, like many others, also uses software called Class Dojo. Teachers project a class list with student aliasas on the wall. Everyone, minute by minute, can see who is getting kudos from the teacher.

A few parents around the state object to that public display of rewards.

Critics of PBIS and other similar systems also say they depend too much on external rewards, rather than fostering good behavior for its own sake. But PBIS is officially sanctioned by the state of Vermont and the federal government, and research shows that schools that adopt it are getting better academic, as well as behavioral, results.