“It’s hard for me to acknowledge progress I’ve made sometimes,” Meghan said, “but when I look back and think of who I was and where I was at and what my life was like on a day-to-day basis 301 days ago, it’s like a 180.”

It was early May, and Meghan was sitting in a food court in a mall in Burlington. Stale pop music played through the overhead speakers, and groups of teenagers occasionally wandered by. A routine mid-week scene, but Meghan was celebrating; 300 days earlier, she woke up and, for the first time in a long time, didn’t go straight for the heroin.

Since then, she’s been trying to rebuild her life. At 24, with a push from her sponsor, she opened a new bank account. It was a big deal. She has a full-time job, and she’s tapering off the suboxone she used to dull the cravings that set in during rehab.

Meghan grew up in Vermont, moving between her parents’ houses in Montpelier and Windsor. Her dark humor belies the optimism she’s found in the past year, but she laughs often – snorting if something’s especially funny. She’s especially present in her recovery, her eyes focused on the conversation, going blank only when she’s recalling her past.

Her features don’t show the bloated fatigue they did when she was using. She used to take pictures of herself on her phone when her mom got home to see how high she looked. She keeps one as a reminder – the soft focus seems to match the subject, her eyes looking at the lens resigned as though she already knows how the picture will look.

Her birthday falls earlier in the year, but this year, July 10 was the most important day for Meghan. She got a new key ring that day, at a 12-step meeting: One year clean.

In the food court in May, she talked about the 12-step meeting she’d just come from. The theme of the meeting was “more will be revealed.”

“It was kind of about how there are all these things that you don’t really think about that will change when you get into recovery,” she said. “My world was so small when I was an active addict, and it just got smaller every day until there was nothing except for me and the drug.”

Now, Meghan takes vacations out of state. She’s thinking about going back to school. She’s excited for the future.

'It Started Out Really Fun'

Substance abuse has always been in Meghan’s life, at least in the background. Her dad was a recovering alcoholic for 10 years – from when she was six to when she was 16.

“When he was sober, he was the picture-perfect father,” she said. “He went to all my plays, all my concerts. Whatever it was, my dad was always there.” She doesn’t talk as much about what he was like after she turned 16.

She remembers her grandfather, a recovering alcoholic, kissing her grandmother goodbye every Tuesday and Thursday before he headed off to his 12-step meetings.

Her mother, she says, worked hard to make sure her kids had a cultured upbringing, taking Meghan and her sister to plays and concerts. Meghan goes out of her way to talk about how “classy” her mother is – and its clear from the letter her mom sent her in rehab that their relationship has been through a lot.

When she was 14, Meghan smoked pot for the first time. She didn’t know much about hard drugs. In small-town Vermont, “it seemed like an abstract concept that there was heroin or cocaine or crack.” But she smoked and occasionally experimented with what she found in her parents’ medicine cabinets.

When she got sick from some of her dad’s pills, he had to take her to the hospital.

“My dad was livid,” she said, “and found out about me smoking pot and some of the people I hung out with that I’d been lying about, and he said he was going to start bringing home drug tests from work, and he said I needed to quit smoking pot.”

She was trying to rebel, but she avoided drugs for a while after the scare. She dropped out of high school at 16, and after a couple years of working and a good SAT score, started taking classes at Champlain College.

“That was when I started to experiment with – I guess I referred to them at the time as ‘real drugs’ – it wasn’t just marijuana and random pills,” she said. “I worked six days a week, I went to school for five, I partied for seven.”

Overwhelmed by college and Burlington, she turned to booze and drugs and men to ease her nerves. Her grades suffered, and her mom pulled her out of school. She took vocational classes to become a nurse, and got a job at a nursing home.

Over the next two years, things got bad.

In February 2009, Meghan’s brother died at age 37 from liver failure due to alcoholism. Two weeks later, her grandfather died. Then her dog. Then her father’s fiancé. Then her grandmother.

“There was so much death all at once,” she said. “I remember feeling this catastrophic grief but I didn’t know who I was grieving for or how to deal with it.”

At age 20, she inherited $5,000 from one of the relatives who’d died.

“I ended up spending it all on hotel rooms, alcohol, acid, mushrooms, ecstasy, molly – I was essentially supporting the guy I was dating, and I got an apartment with that money, and it was gone within a couple months.”

Her relationship was on-again-off-again, and Meghan found herself unable to face reality alone.

“I still felt so un-okay about myself. I felt so strange in my own body,” she said. “I was not comfortable with myself at all, and so I used men and sex and relationships to feel okay.”

"I still felt so un-okay about myself. I felt so strange in my own body. I was not comfortable with myself at all, and so I used men and sex and relationships to feel okay." - Meghan

Then she found heroin. She didn’t like it the first time she used, but a few months later she tried again, and all of that discomfort faded away.

“All this time that I had felt different, that I had not liked myself, that I had felt ugly or unattractive or not good enough – all of that was just gone when I was using heroin,” she said. “It started out really fun.”

‘Wash, Rinse, Repeat’

For the next two years, Meghan’s life revolved around her next high.

“It’s the same thing everyday,” she remembers. “Wake up, find drugs, get high, come down, find more drugs. Or wake up, can’t find drugs, be sick, do desperate, terrible things to find drugs. Wash, rinse, repeat. Pretty much every single day.”

The search for heroin brought Meghan to a gas station, where she met a guy from New York City. He invited her to his hotel room “to try some heroin that he had that he was trying to sell up here.” She went with him for a free sample.

“What ended up happening was I was raped,” she said. “He did give some drugs, and I got so high that it made it very easy for him, and I just kind of checked out.”

For weeks, she didn’t acknowledge it. She kept getting high.

“My drug use got a lot worse, I got a lot deeper into things,” she said. “A couple weeks later I found out I had gotten pregnant and I had an abortion.”

She’d spent all of her money on drugs, so she got a credit card and paid for the abortion with that.

She stayed on heroin, “self-medicating” for the physical and emotional pain she was in.

“There are all of these horror stories about all these things that addicts do when we’re on drugs, and I did most of them,” she said.

"There are all of these horror stories about all these things that addicts do when we're on drugs, and I did most of them." - Meghan

Sexual favors, stealing, manipulation; Meghan doesn’t shy away from what she’s done, but she spends every day distancing herself from the person she is when she’s using, and from the intense hold of addiction.

“You just always want more,” she said, thinking back. “There’s not enough drugs in the world to satisfy an addict in active addiction. I would kill myself first, and I almost have.”

Meghan finally started to realize that she was an addict when she overdosed on a mix of cocaine and heroin.

“I shot it up and I was trying to stand up so I could walk to the bathroom and vomit, and apparently I’d fallen over and was still moving my legs as though I was walking,” she said. “I got tunnel vision and I thought I was gonna die. But I didn’t, and I ended up coming down, and when I wasn’t high anymore and I still had drugs left, I did it again.”

These experiences left an impression, but one of the worst memories Meghan has of active addiction didn’t happen when she was shooting up.

“One of the worst images I have in my head is my mom, who’s this beautiful, classy, educated, cultured woman, holding this nasty bag of syringes and empty bags of heroin and confronting me with it,” she said. At the time, Meghan snatched the bag out of her mom’s hand and ran out of the house, but the image lingered.

“I wish I didn’t know what she looked like holding those things,” she said, “because I didn’t want those two pieces of my life to intersect.”

With her mom pressing her to get help, Meghan went to rehab. She hated it, and she left after two weeks. She met up with some friends when she got out, and within a week she was getting high again.

“What I realized is that I can never have one last hurrah because it will never be good enough until I’m dead,” she said.

Proud and Powerless

A few days into her second rehab, a girl she was there with asked Meghan if she wanted to go get high together “one last time” after they got out.

“I was like ‘No. No dude, come on.’ And I was trying to talk her out of it and it made me listen to what I was actually saying to her and realize that I actually believed what I was saying,” she said. It was a new feeling.

“I was so used to just handing out random BS to everyone, and I was such a good manipulator and liar, and I realized that I actually believed what I was saying,” she pauses, thinking back. “That was really cool.”

The feeling stuck.

It’s been more than a year now since Meghan used. One of her best friends is Sonja, a 19-year-old recovering addict. Sonja was the first one to introduce herself to Meghan at a 12-step meeting, and she knew right away that she wanted to sponsor Meghan.

After reaching one year of clean time, addicts in the 12-step program are able to become sponsors. The last time Sonja did drugs, she wasn’t even legally an adult. Even though she’s five years younger than Meghan, she’s been instrumental in getting her through the past year.

“I can’t really say that I could be any more proud of her,” Sonja said of Meghan.

As recovering addicts, Sonja and Meghan have an interesting relationship with pride – it’s built right into their 12-step program. Step one for members is to admit total powerlessness over their addiction; every time they go to a meeting, they introduce themselves as addicts.

“There’s different types of pride, I guess,” Sonja said. “There’s people that pride themselves on thinking they can do everything on their own and that they don’t need anybody’s help and that they don’t struggle.”

Those people, Sonja says, usually don’t do well in the program.

"Meghan is proud of the fact that she doesn't wake up every morning and have to get high, or have to shoot heroin or else she'll get sick, or have to go sleep with guys to feed her habit." - Sonja, Meghan's sponsor

“Meghan is proud in the sense of the accomplishments, and the thing that she’s most proud of herself is her clean time, and I can say that without any doubt in my mind.”

The victories, for both Meghan and Sonja, can seem obvious or insignificant to people who don’t struggle with addiction – “normies” in Meghan and Sonja’s terms.

“Meghan is proud of the fact that she doesn’t wake up every morning and have to get high, or have to shoot heroin or else she’ll get sick, or have to go sleep with guys to feed her habit,” Sonja said. “She’s proud that she doesn’t have to do that, and it’s not a struggle for her to understand that she doesn’t have control over her addiction.”

Sonja sees how, to a “normy,” it could seem strange, even humiliating, for a 24-year-old to be celebrating something as basic as getting a bank account. But it doesn’t bother her, and when she talks about convincing Meghan to get a bank account and Meghan finally doing it, she can’t keep the proud smile off her face.

“I think that in early recovery, you need to be able to be proud of yourself for those small things like getting a bank account,” Sonja says. The people with the big egos, she says, will try to play it off like it isn’t a big deal, but “when it comes down to it, for someone who’s spent a long time hiding their money under a mattress, and thinking the government was out to get them, and that all the banks were corrupt and someone was going to steal their money, and would cut holes in a wall to save money in there – for someone that did that for years, for them to go out and to actually do all the things that they had this really, maybe irrational fear about, is huge. It’s such a big thing.”

Sonja said these uncomfortable moments in recovery are the ones where having a sponsor is key. Sometimes, hearing it from someone who’s been there before is the only thing that helps.

The Payoff

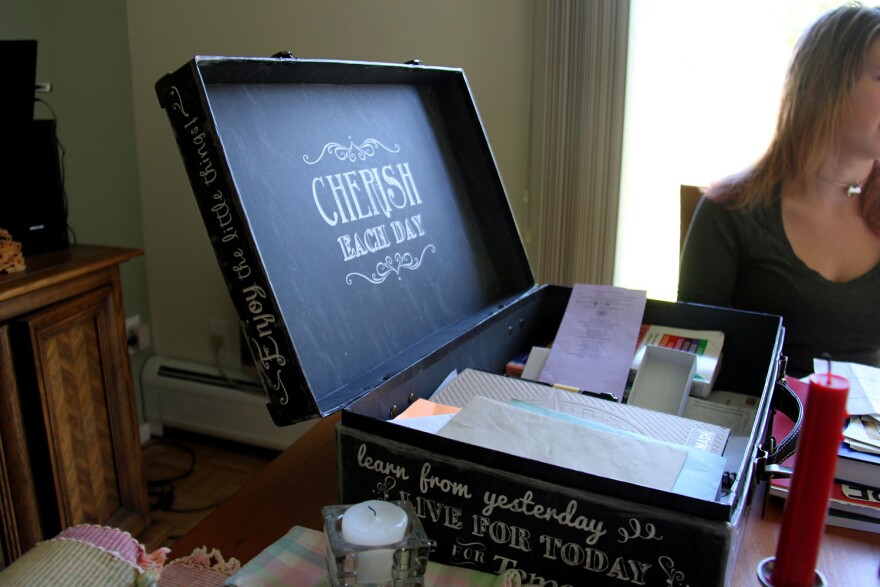

Sitting in the dining room at her mother’s condo in South Burlington, Meghan is smiling. On the other side of the one year mark, it feels different, she says. She’s been busy, with a new full-time job and 12-step meetings, but she made the hurdle.

The satisfaction of one year is apparent. She’s had a birthday without getting high, she’s done Thanksgiving, Christmas and all four seasons. The new challenge is to do that again, every year, for the rest of her life.

The suboxone she’s been on for the past year has served its purpose, she said.

“It helped the physical stuff” – the withdrawal symptoms, the physical dependence her body had on heroin. But even at the beginning of her recovery, “I was still mentally emotionally and spiritually a disaster. I was bankrupt. And just being on medication did not treat the behaviors, the thought process, all these things that just made me such a dysfunctional, unmanageable person.”

So while suboxone quieted the physical symptoms, she worked on her mind.

“That’s what the 12-step groups have done for me,” she said. “Through step work, through my sponsor, through meetings talking to other addicts, I’ve been able to change the way I react to situations. So my first reaction isn’t ‘Oh my god, I’m uncomfortable, what’s going to make me feel better?’ or ‘I need drugs,’ or ‘I need sex,’ or ‘I need to shop.’ I’m able to take a step back and just feel what I’m feeling and be okay with it.”

Looking back, she’s mad at herself sometimes for the lost years.

“I just feel like I’ve wasted a lot of my life,” she said. “I just feel like I’ve been sleepwalking for the past five years. There’s just huge gaps of time I just don’t remember, and I feel really stunted sometimes, because I feel like there’s so much more I could have accomplished by now if I hadn’t gotten sidetracked.”

"I just feel like I've been sleepwalking for the past five years. There's just huge gaps of time I just don't remember, and I feel really stunted sometimes, because I feel like there's so much more I could have accomplished by now if I hadn't gotten sidetracked."

But she has time now, and she’s thinking of going back to school. Even though being around college parties would be hard, she says all of her opportunities look different now.

“All of these things I just wouldn’t be doing if I wasn’t clean, and they’re just kind of sweeter because I know I have these things because of the work I put in,” she said. “So it’s kind of like a payoff I guess.”

After the one-year mark, she speaks with more confidence about her recovery. She knows she’s not “cured,” but she knows how to get through life without running from discomfort.

“I don’t know the future,” she said, “but I know that I can stay clean through anything if I do the things that I need to.”