For many people with epilepsy, seizures are debilitating, dangerous, and unavoidable.

But a new device approved by the Food and Drug Administration last year offers new hope and stunning results.

Clinical studies of the device were conducted at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Epilepsy Center in Lebanon, N.H. Some patients there are now going to able to live much more independently with tiny computers embedded in their skulls.

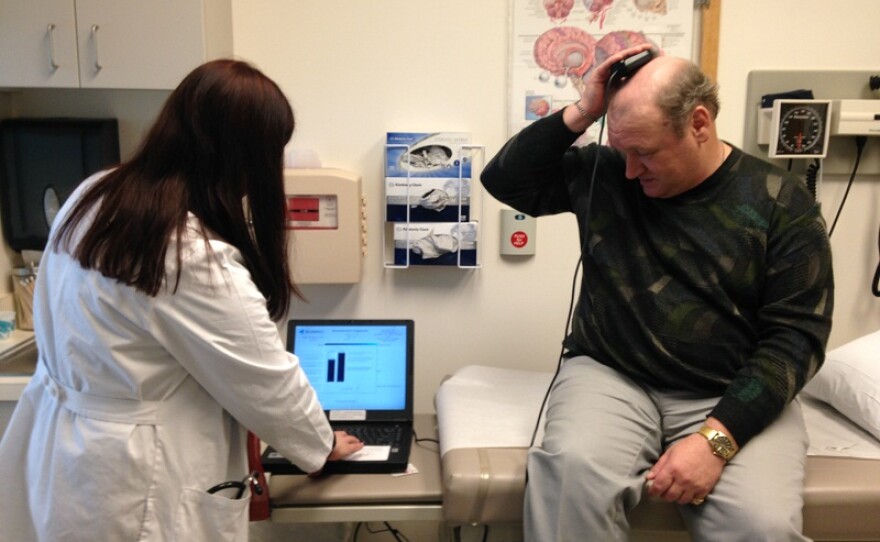

One of them is Mark McKinstry, of Barre. He sits on an examining table at the hospital and holds a tiny receptor about the size of a half-dollar on his head. It’s literally reading brain waves that appear on a nearby computer screen monitored by his doctor, Barbara Jobst.

“In a few seconds you will see his actual brain waves, from inside his brain,” Jobst says, peering at the screen.

Inside McKinstry’s brain, there’s another, much tinier computer with cables touching the parts of his lobes that trigger seizures. If he were to have a seizure right now, the device would spring into action.

“Whenever it sees a seizure or activity that looks like a seizure, then the device delivers a stimulus to abort this activity,” Jobst explains.

In other words, it would stop the seizure in its tracks, or at least dramatically shorten it. At the end of each day, at the home he shares with his parents, the 49-year-old McKinstry holds the external receptor on his head to download data from his own brain. He sends the computer file to a secure server so his doctors can keep track of how well his device is working.

He’s really a walking science lab, because he participated in a study at Dartmouth-Hitchock to test the efficacy and safety of this device.

“I was very skeptical, to start with, I’ll admit,” says McKinstry.

But he decided to give it a try. Despite his fierce independence, his seizures were making life almost unbearable at times.

“Prior to the operation, I would have approximately six seizures per month, too, and they would last a much longer period of time per seizure. Since the operation I think the most I have ever had is two per month, and ... they are very, very short. I am just in and out in a split second,” McKinstry says.

"Whenever it sees a seizure or activity that looks like a seizure, then the device delivers a stimulus to abort this activity." - Barbara Jobst, Dartmouth-Hitchcock physician

That’s increased his range of activities and allowed his parents to get out of the house, more, too. His mother Sylvia says he was only four when his severe epilepsy was diagnosed — possibly, she says, as a result of blows during youth hockey and football. She says the clinical study may have been risky, but it held out hope.

"And he was a good candidate for it so he decided that he had nothing to lose, really in one sense,” Sylvia McKinstry says.

Good candidates, Dr. Jobst says, are those who cannot be helped with conventional brain surgery, perhaps because their seizures come from parts of the brain that cannot or should not be operated on.

She says since the FDA has approved this device, another patient has received it at Dartmouth-Hitchcock, and others are likely to follow, both there and nationwide. She says insurers are likely to cover the procedure, because the alternative — trips to emergency rooms after grand mal seizures — could be even costlier, over a lifetime.