Over the next three years, jobs in law enforcement, investigation, paralegal services, and corrections are expected to grow by as much as 12 percent. Not a staggering hike, perhaps, but apparently reason enough for colleges to add or expand criminal justice curricula. There are now at least nine such programs in Vermont—ten in New Hampshire--offering a wide range of courses in this growing and rapidly changing field.

One is at Norwich University in Northfield.

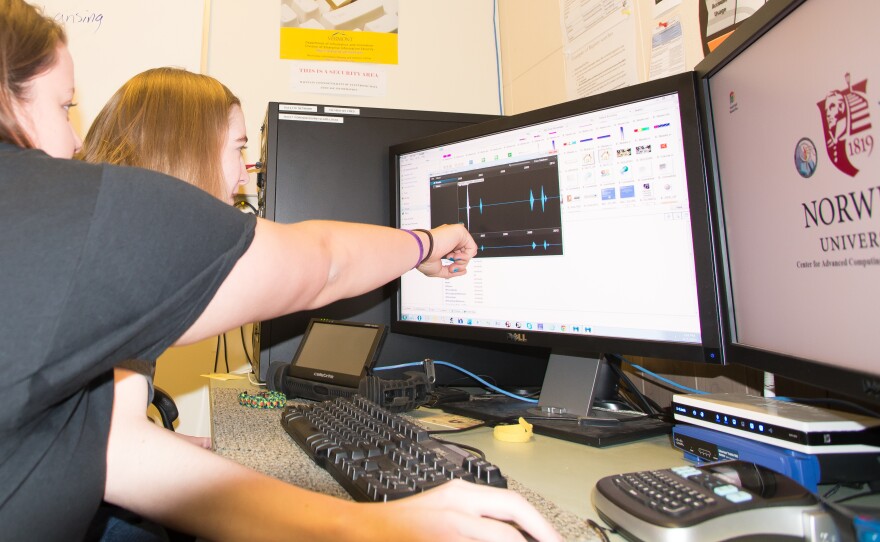

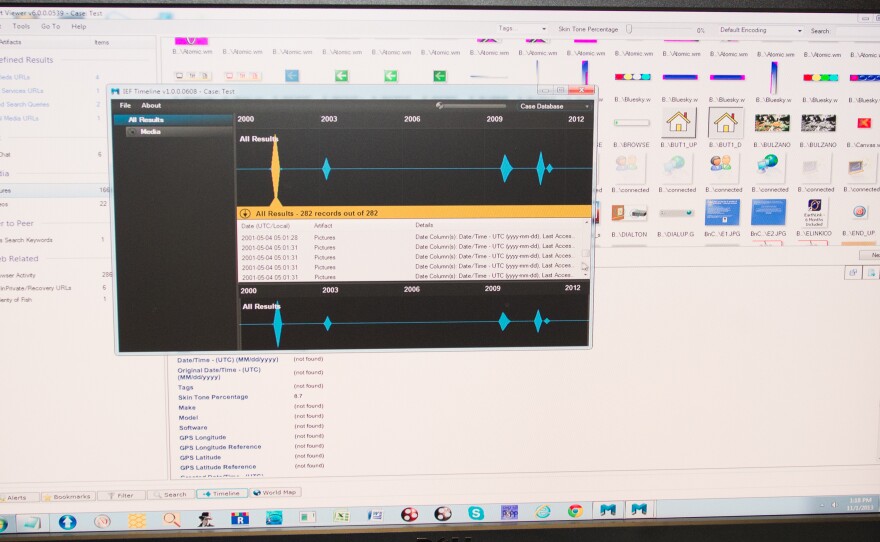

Tapping away on computers in an up-to-date lab, about a dozen budding investigators there are trying to solve a cyber crime. This is not a textbook exercise, it’s a real unsolved fraud case, as Professor Peter Stephenson explained.

“And they have forensic images of computers that the alleged fraudster used for some period of time. They have access to witnesses, actual witnesses. They’re preparing this for a mock trial.”

Christian Bulhuis, a senior, transferred from Virginia to get his degree here.

His prosecutors team's mock trial case is about an actual man—not from Vermont—who has allegedly been using Facebook to scam people.

“Not really assaulting them or anything like that, but he’s generally a jerk online,” Bulhuis said. “He’s extorted money out of people, he’s had them send them money with promise of him going there and meeting up with them, and he impersonates a rich person or something like that to get these peoples’ attention.”

This case was originally investigated by the FBI, but it’s gone cold. If the students do find incriminating bread crumbs on the hard drive, they’d pass that information on in hopes of getting it re-opened.

But at the other end of the room, Rebecca Weaver’s team is planning to use that same de-crypted hard drive to defend this guy in the mock trial.

“I really don’t think they are going to find anything,” she declared confidently.

It’s not that she doesn’t see signs of criminal activity on the hard drive. But it’s fodder for charges not being brought in the forthcoming mock trial.

“For like cyber stalking, of course, there’s a ton on there. But that’s not [the case] we are trying,” she explained.

"The current backlog for digital forensic cases in Vermont is about two years, so the small police departments don't have the facilities to handle this themselves." -Norwich University Professor Peter Stephenson

So Weaver thinks her team will win. Women, it turns out, are flocking to cyber forensics courses like this one—and to jobs afterwards. Professor Stephenson calls that the “Abby” syndrome, after the hugely popular TV star of the police procedural drama, NCIS.

“It turns out in forensics that about 70 percent of the people going into the field are women,” he said.

And Stephenson wants both female and male student detectives to help out Vermont police departments, even before they graduate.

“The current backlog for digital forensic cases in Vermont is about two years, so the small police departments don’t have the facilities to handle this themselves,” he said.

A nationally recognized program at Champlain College is already partnering with the Burlington Police.

But in addition to specialized forensic detectives, there’s a need for more cops on the beat, paralegals, and corrections workers. That’s one reason Lyndon State College is now offering a criminal justice degree. Lyndon Sociology Professor Janet Bennion says its three-year-old program is based solidly on liberal arts.

“So we’re really looking at a behavioral science, social science template for answering 'why do people do what they do?'” Bennion said.

Why, in other words, do they commit crimes? Bennion says studying sociology and psychology builds empathy, as well as teaching investigators to think like criminals. And she says LSC students will get lots of practical experience through internships in prisons, police departments, the border patrol, criminal law offices, and the courts.