The dangers of building in a flood plain were one of the big lessons of Tropical Storm Irene. But many of Vermont’s historic villages were built along rivers. After the storm, most had little choice but to rebuild in high risk areas.

Dot’s restaurant in Wilmington saw heavy damage in the storm. More than two years after Irene, the popular eatery is almost ready to re-open.

Dot’s owners, John and Patty Reagan, thought at first they’d never rebuild.

Patty Reagan laughs. “Our first thought was, you’d have to be crazy.”

But the Reagans knew that Dot’s was important to Wilmington and to generations of tourists. In the end they decided it was possible to rebuild in a way that could lessen the damage in future floods.

The restaurant is directly in the path of the Deerfield River.

“That hasn’t changed,” John Reagan says.

But some things have changed. The building’s utilities and furnace are now on the second floor. Aluminum floodgates protect the doors.

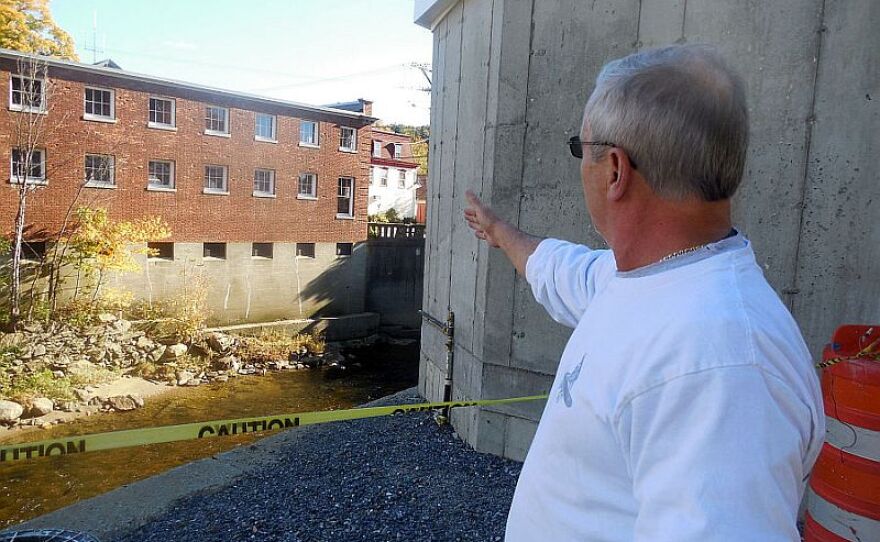

John Reagan leads the way out to the back of the building. In Irene, the back wall was splintered by eight or nine feet of water and debris. The wall has been replaced by a thick slab of reinforced concrete, angled to deflect water around the building instead of straight at it.

The flood-proofing strategy was designed by Bob Stevens a Brattleboro-based structural engineer.

Stevens’ first priority was to raise the building to the highest elevation possible, about eighteen inches as it turned out.

“That was enough to meet the regulatory threshold for a 100 year flood,” Stevens says. “But it still put us quite a bit under water in an event like Irene.”

So Stevens made sure the basement and foundation were tight and strong enough to withstand a flood like Irene. Then he realized that he had essentially designed a concrete boat.

“The weight of the building wasn’t enough to keep it in place with that much water over it,” Stevens says. “It was going to lift out of the ground and float downstream.”

Builders often place vents in the walls of flood-prone basements to let in enough water to equalize the pressure so the building won’t collapse as water pushes against it.

At Dot’s the holes are in the floor, to keep the water level from getting too high.

“And it’s a calculated risk,” says Stevens, “That we can pump it out fast enough so it doesn’t hit the finished floor above.”

Stevens was asked by the Preservation Trust of Vermont to visit other flood-damaged towns to talk about flood proofing historic buildings. He says strategies like his are being used throughout the state.

The fire house in Waterbury, which was built before Irene, has its basement partly filled with concrete so it won’t fill up with water or lift off its foundation.

Community planner Steve Lotspiech says Waterbury requires anyone rebuilding in a flood zone to securely anchor oil and propane tanks.

Lotspiech says there are many things homeowners can do. “When people reinsulated,” he says, “We encouraged people to use flood- resistant material like closed cell foam insulation rather than fiber glass. Fiber glass is kind of a disaster when it gets wet.”

Sheetrock was another material that caused problems, especially with mold, in homes damaged by Irene.

Bob Stevens urges homeowners to consider replacing sheetrock with removable wainscoting.

“Putting in a chair rail at three feet high,” suggests, “With a panel down below so you can take the chair rail off and take the panel out and dry the walls out and put them back together.”

Scientists say it’s best not to build in a flood plain. People in Wilmington actually discussed moving the town to higher ground and decided it couldn’t be done.

As Stevens says, sometimes the only option left is to try and minimize the damage.