Twenty years ago, the United States built a military prison on the naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Since then, it’s been used to hold what the U.S. government calls “enemy combatants” from the War on Terror, putting them outside international legal systems. This hour, we'll speak to two Vermonters who worked for years to free one detainee, and we’ll reflect on the legacy of the prison 20 years after it opened.

Our guests are:

- David Sleigh, a St. Johnsbury attorney who was among a handful of Vermont attorneys who volunteered to represent detainees held at the Guantanamo Bay prison

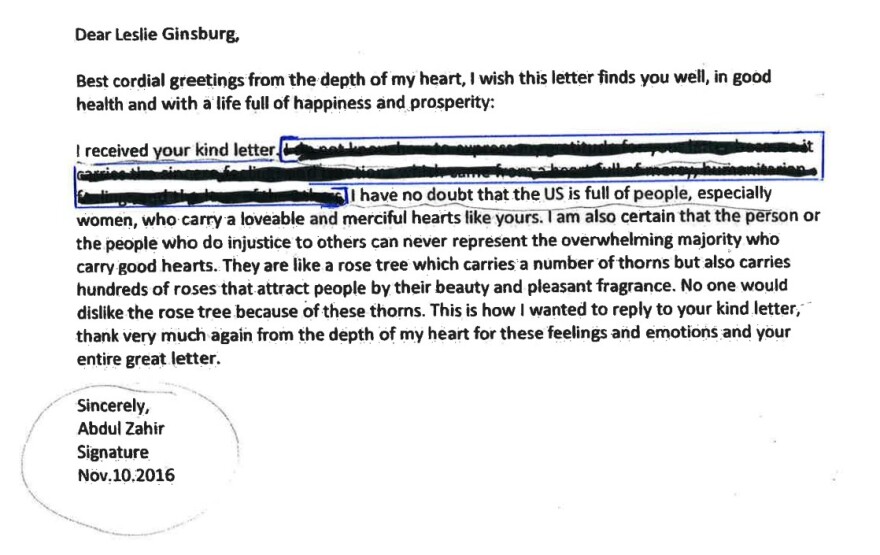

- Leslie Gensburg, the widow of Bob Gensburg, who along with Sleigh represented Abdul Zahir, winning his freedom after more than a decade of detention; she also exchanged letters with Zahir during his imprisonment

David Sleigh on why Guantanamo Bay differs from other military prisons:

Sleigh: It differs mostly in its design, which was to evade United States constitutional protections and to evade compliance by the United States with the pertinent Geneva Conventions, as they regulate the treatment of prisoners seized in conflict.

I would think most prisons' goal is to try to consistently apply punishment, deterrence, disability, for people who had been found to have broken the law. Gitmo's primary purpose was to evade the application of the law.

That's the entire reason it was in Cuba. In 2002, after the [Sept. 11] terrorist attacks, the Bush administration sought a way to gather and detain people that they had newly minted as "enemy combatants," in a way that would avoid scrutiny and avoid review. The notion was that the United States Naval base down at Guantanamo Bay was not on territory that was adequately controlled by the United States. And thus, would be outside the application of United States constitutional law. And so, that was the entire design.

David Sleigh on how he and Bob Gensburg got involved representing Guantanamo detainees:

[Since the prison opened in January 2002] there was absolutely no access to lawyers for any prisoners. That was the administration's design. That was what was going on.

So, in 2004, when the Center for Constitutional Rights prevailed [in its habeus corpus petitions to the U.S. Supreme Court], suddenly they had 600 people who needed lawyers. And they went on a recruiting mission. I had just won a prison malpractice case, in the Seventh Circuit out in Chicago, and that made some news amongst the prison law set. And the Constitutional Rights folks just called me, as a cold call, [and asked], would you be willing to represent some Guantanamo prisoners? And I was, of course, absolutely delighted to be able to do that.

It's the most important work I think I've ever done in the 39 years that I've been practicing. It struck me as just inconceivable that the United States government would endeavor, with such cold calculation, to create a system that would deny people basic human rights. It seemed completely at odds with the whole experiment that is the United States. And I was happy to join to try to rectify that.

Leslie Gensburg on exchanging letters with Abdul Zahir:

[Well into the roughly decade-long fight to free Zahir], in 2016, when it had just gotten so on edge—the Obama administration had come in, things had relaxed somewhat, and Bob and Dave were trying like mad to get him out of there—especially before the terrible change of administrations—and I asked Bob, at some point, would it be okay, do you think they would allow me, to give you a letter to him?

And he said, write it, and I will see, and if they let him have it, fine. And they did.

And what I wanted to say to him, what I did say to him, was just how ashamed I was of my country, and what it had done to him and the others. And I just expressed my ... I wanted him to know that not everybody in America was like that. And he wrote me back [in November 2016].

David Sleigh on helping secure Abdul Zahir's freedom:

The U.S. military forces entered Zahir's family home and arrested him on July the 11, 2002. They seized from the home three pressure cookers, where two had a white powdery-type ingredients. One had something that looked more like gel. Within 48 hours of the seizure of the pressure cookers—that were thought to contain bomb-making supplies—they identified the contents as salt, sugar and petroleum jelly.

From July 11, 2002, until October 28, 2002, Tuesday here was either at Bagram Air Force Base, or a dark site in Central Europe, where he was tortured. He was brought to Guantanamo [and] tortured some more,

When we finally, after years of begging, had an opportunity to present some evidence in June 2016, the the Review Board found that Zahir was subjected to release, and they confessed that his detention likely sprung from misidentification.

He languished in Guantanamo, from July 2016 until Jan. 17, 2017—four days before Trump was to be inaugurated. Trump had made it clear that no one was going to leave Guantanamo once he became president. And I know all of us were sweating bullets that Zahir would go "wheels up" sometime before the inauguration. And, in fact, we weren't sure where he was when the President was inaugurated. And I feared that the President would tell the Air Force to turn around and bring Zahir back. And it wasn't until sometime after the inauguration that it was confirmed to us that Zach here had landed in Oman.

Sleigh on why Americans should care about the fate of Gauntanamo detainees:

Very few people [detained at Guantanamo Bay] have been charged with crimes and convicted of anything. That might be because very few people were afforded a right to have a trial. But the vast majority of the people that were imprisoned there have been OK'd for release, after the United States government found them not to be a threat to the United States, or anybody else.

One of the fundamental aspects of our system of justice is that you cannot deprive somebody of their liberty, without proof that that deprivation is legally based. That's really what it means to be an American. And so, having concerns for people who are imprisoned, and who are denied at trial, is really, I think, a fundamental value, in and of itself.

I, and certainly Bob, have enormous faith in the United States system of criminal justice. Had the perpetrators of the Sept. 11 attacks and other terrorist actions been tried publicly, in United States criminal courts, so the world could see the evidence and the juries could come to their verdicts, the United States would have lived up to its reputation as the shining city on the hill, rather than a bunch of cowards.

Broadcast live at noon on Thursday, June 23, 2022; rebroadcast at 7 p.m.

Share your questions for the candidates: email Vermont Edition or tweet us @vermontedition.