Just after 10 a.m., Keith Klepeis was writing a paper at his desk in Essex Junction, when he heard a low rumble, like a truck. Then, he noticed his computer monitor looked like it was twisting. “A truck wouldn't do that, so that's what gave it away for me,” he said.

Moments earlier, a relatively small earthquake hit New Jersey. Klepeis, a geologist at the University of Vermont, realized what he was experiencing: the initial fast waves that can produce a sound, followed by slower waves that move like ripples.

Small earthquakes are fairly common along the east coast, from old faults leftover from ancient geologic activity, like when the Appalachian Mountains formed or North America drifted away from Europe and Africa.

"There are still remnants of that past activity buried underneath the ground. And they whisper every once in a while and say, 'remember, I'm still here.'”Dave West, Middlebury College

But we don’t usually feel them.

“It's definitely really exciting,” said Dave West, a geologist at Middlebury College who studies ancient faults. “It kind of lets you know that the earth is alive.”

Hundreds of millions of years ago, this area had massive earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, he said. “There are still remnants of that past activity buried underneath the ground. And they whisper every once in a while and say, 'remember, I'm still here.'”

There are a number of theories about the source of this seismic energy so far from a plate tectonic boundary.

“This is all speculation, but I could think that possibly those stresses might be due to the rebounding of the earth’s crust after the ice age,” said Leslie Sonder, a geologist at Dartmouth College.

Even thousands of years after the glaciers receded, the earth’s crust might still be springing up, after being pressed down by so much weight. “That slow rebound might cause enough stress to cause the occasional earthquake.”

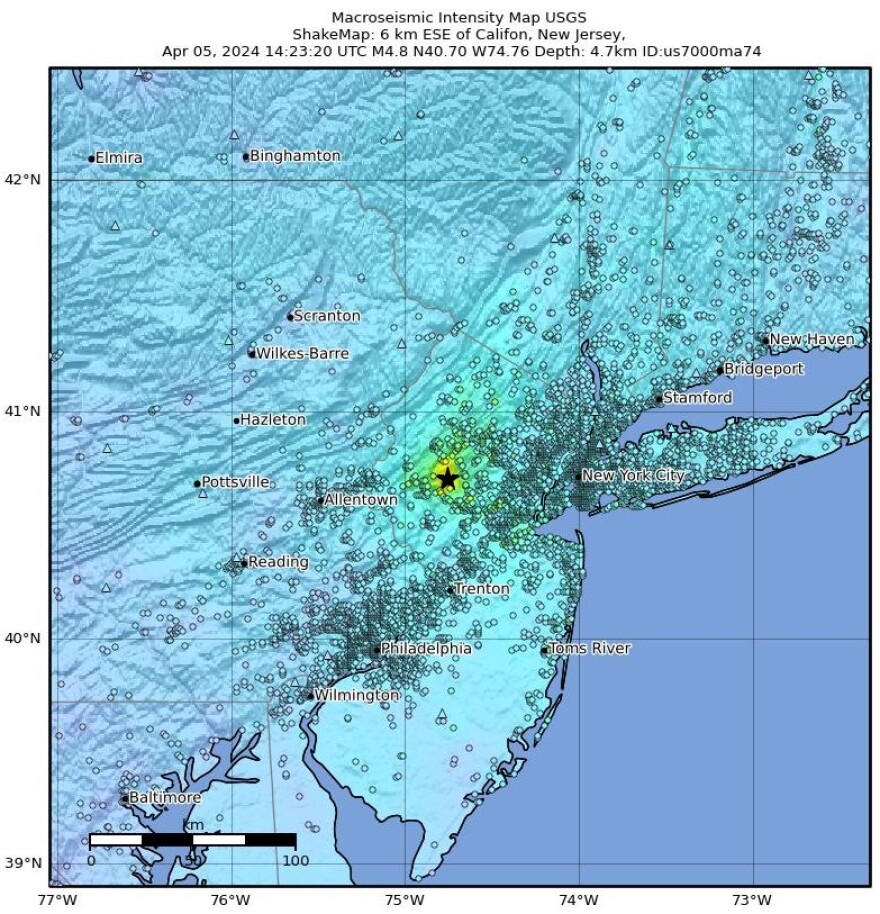

Whatever the cause, we can detect this geologic activity very quickly because of a network of instruments spread out all over the world, including New England, that pick up sound and sense motion in the ground. Those stations can triangulate where and how deep underground an earthquake occurred.

While most earthquakes along the east coast aren’t very big, they can be felt hundreds of miles away because of the geology here. Rocks that make up the Appalachians are older, cooler and more dense than much of the geology of the western U.S.

“What that does is it allows the earthquake waves to propagate a lot farther,” said Klepeis, from the University of Vermont.

“That's why me, sitting up here in Vermont, I can feel those surface waves really strongly, even though the source was in New Jersey.”

Have questions, comments or tips? Send us a message.