The total solar eclipse on April 8 will be a few hours unlike any other in the past 90 years.

On Monday, from about 2-4 p.m., the moon’s orbit takes it directly between the sun and the earth, creating a small shadow on the earth. Due to the motion of the moon, and the spin of the earth, this shadow starts in the Pacific, a little south of the equator as the sun rises, sweeping northeast to the coast of Mexico near Mazatlan just after 2 p.m. our time. It then streaks through Texas, right over Dallas; just north of Little Rock, Arkansas; through Cape Girardeau, Missouri; Indianapolis, Indiana; on to Cleveland, Buffalo, and continues right over the northern portions of our region; finally making its way through northern Maine, New Brunswick, and then southern Newfoundland, ending just before 4 p.m. our time in the central Atlantic.

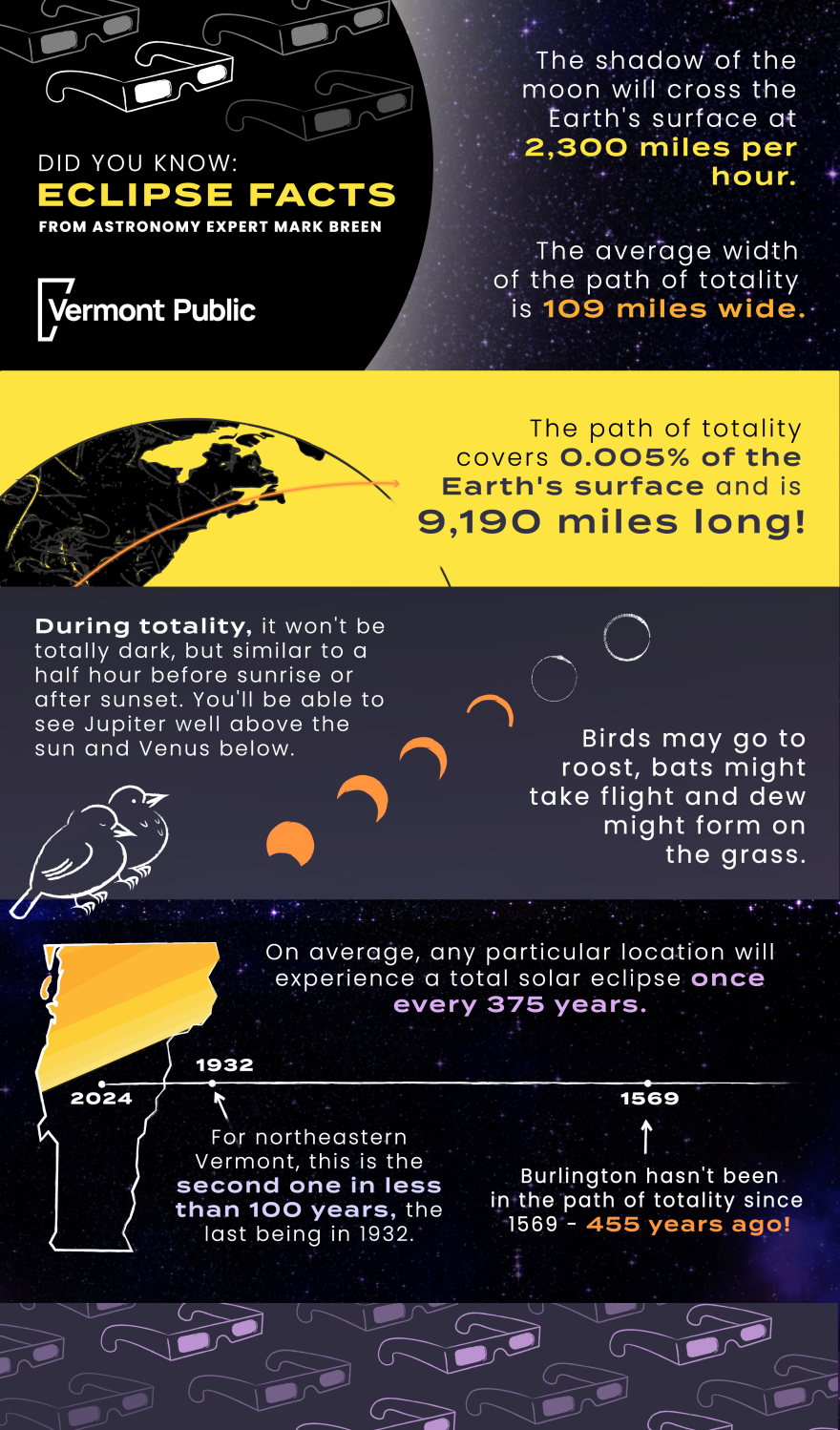

This means the shadow of the moon zips across the earth’s surface at a blazing rate of 2,300 miles per hour. And while the length of this path stretches for 9,190 miles, and averages 109 miles in width, it actually only covers 0.005% of the earth’s surface.

Total solar eclipses, in any particular location, are rare. The average is once every 375 years. For northeastern Vermont, much of New Hampshire, and western Maine, this is the second one in less than 100 years, the last in 1932. But for Burlington, Vermont, you have to go back to 1569 — 455 years — to find a total solar eclipse. Obviously, this alignment of the earth, moon and sun must have to be quite precise.

Each month, as the moon orbits the earth, it passes between the earth and the sun, at an average of 29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes and 2.9 seconds. It varies by several hours because the moon varies its speed due to its elliptical orbit — not quite circular. It moves a little faster when it is closer, and a little slower when it is farther from the earth. Regardless, even though the moon passes between us and the sun, we don’t experience eclipses each month.

Two details are critical to produce the required precise alignment. First, the moon’s orbit is tilted at 5 degrees compared to the earth, yet the sun is only one-half a degree in the sky, creating a significant margin of error. Second, the moon’s elliptical orbit changes its distance from the earth, and therefore changes its apparent size. At its most distant, it does not completely cover the sun’s disc.

Totality can last from a few seconds to over 7 minutes, depending on the circumstances. On April 8, those along the central eclipse line from the Adirondacks through St. Albans and then just north of Newport, will see 3-and-a-half minutes, a little longer than usual.

MAP: See the path of the 2024 total solar eclipse in Vermont

What can be seen during totality?

First, while still wearing eye protection, the last moments before totality include a phenomenon called the Diamond Ring, when the last of the sun gleams almost as a point, and just enough light to show the curve of the moon as the ring. Next, very tiny specks of sunlight will be briefly visible as the edge of the moon gets ready to cover the sun. These pieces of light happen as the sunlight passes through valleys between mountains on the moon. They are known as Baily’s Beads, after Francis Baily, an English astronomer who first recorded them in 1836. When those beads disappear, it is safe to remove your eclipse glasses. You will see a ghostly light around the sun: the corona.

During totality, it will not be totally dark, but similar to one half hour before sunrise, or after sunset, enough to see the planet Jupiter well above the sun, and Venus below. A few of Orion’s bright stars may be visible in the south. Birds may go to roost; bats might take to flight. Dew might form on the grass. But the most rare, more interesting event will be the ghostly, vaporous light dancing around the edge of the moon, the sun’s corona. You are witnessing the sun’s atmosphere of ionized gasses, known as plasma, approximately one million times hotter than the surface of the sun, though it is so thin that it shines a million times less bright than the sun, which is why it is only visible during a solar eclipse.

Eye on the Night Sky, a production of Vermont Public and the Fairbanks Museum and Planetarium, airs on Vermont Public's main radio station every weekday during All Things Considered.

More eclipse resources

- See our eclipse liveblog for the latest updates.

- Watch our half-hour educational TV special, "Path to Totality."

- See our interactive map of the eclipse path.

- Plan for road closures around the state.

- Get updates on the weather forecast for Monday.

- Emergency management officials share travel and communication tips.

- Where to find eclipse glasses.

- Learning guides for preK-12 educators.

- Details on our live event in St. Johnsbury and other events around the state.

See all of Vermont Public's 2024 eclipse coverage.