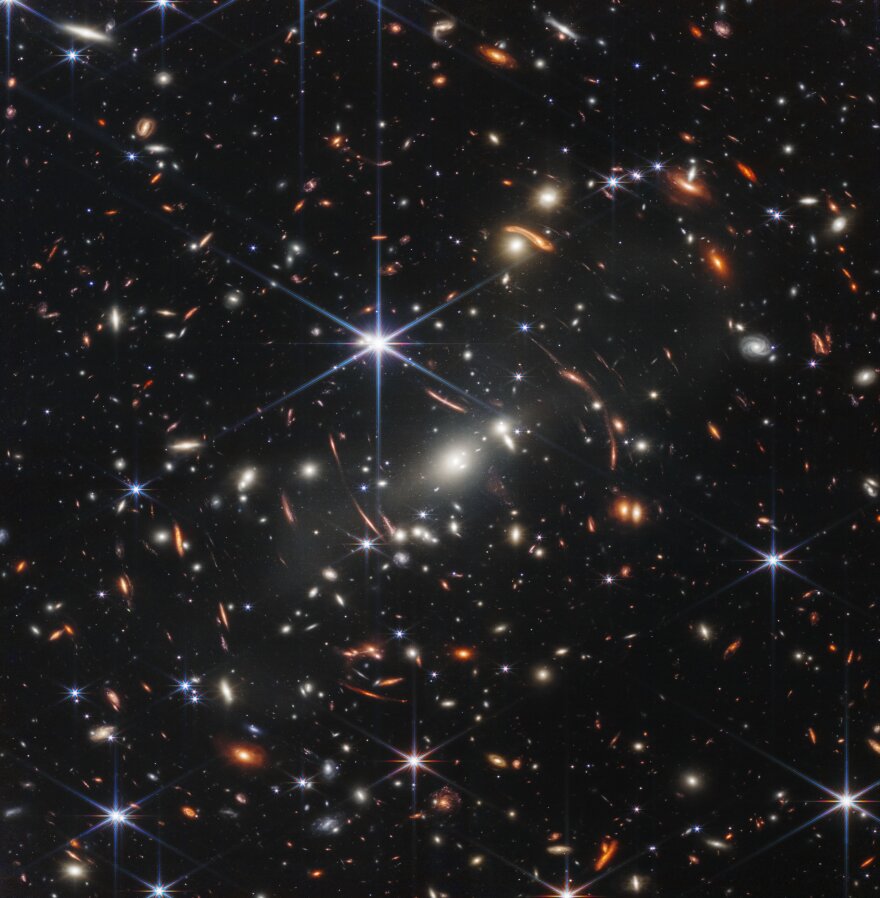

The most powerful telescope ever built has photographed some of the very first galaxies to form in the universe.

The White House released the first image from the James Webb Space Telescope during a preview event on Monday. The telescope is the most sophisticated observatory ever launched, and it left Earth six months ago to journey to its temporary home about a million miles away.

The Webb Telescope is designed to gather and analyze infrared light, which cannot be seen by the human eye.

And on Tuesday morning, NASA released several more images from the telescope. Just before the reveal, we spoke with one of the space experts at the event about what pictures like this can tell us.

Vermont Public’s Mitch Wertlieb spoke with University of Montreal professor René Doyon, an expert in astronomical instrumentation and exoplanets. Their conversation below has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Mitch Wertlieb: Have you seen this full collection of images yet?

René Doyon: The images were revealed to us a few days ago, and they're just absolutely stunning. You're gonna, you know, it breaks a jaw, to see these beautiful images and spectroscopic data.

What's so incredible about them? What stands out to them more than other images you've seen from telescopes over the years?

Well, it's the perspective. Webb is an infrared telescope and give us access to new colors, new wavelength that Hubble cannot give us. And so we really have a new perspective that we cannot get with Hubble.

And it's also the crispness of these images. They're very sharp, because the telescope is much larger than Hubble. And, you know, compared to previous telescope, like also Spitzer, that it was operating at wavelengths similar to the new instrument. That was a little telescope, 85-centimeter mirror, and this one is 6.5 meters. So the images are very, very sharp. It's difficult to describe, you'll have to see them.

I imagine so, and I think a lot of people are going to be really, really looking forward to seeing these images. How far back did these pictures go related to the origin of the universe as we know it from the Big Bang?

Well, they go back to about 13 billion years ago. So the universe is 13.8 billion years [old]. And we think that the very first stars, the very first galaxies, lit up, we think, a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. In fact, that's the big question we're trying to answer with Webb. And Hubble cannot really go back to maybe, at that length, 12.5, 12.8 billion years. But now we're gonna go close to 13.

All images and data you're going to see today, is only 120 hours. Well, there are more than 6,000 useful hours you can use every year, years after years, day and night with Webb. So this is literally a tsunami of data that's just about to start.

"Today, we're turning the page on several new chapters to understand the universe, from the early universe, exoplanet atmospheres, how stars and planetary systems form, and many other things."René Doyon, University of Montreal

Tsunami of data — incredible. Well, that brings the question, then, what are astronomers like yourself hoping to learn from these images?

Well, the images actually represent the various science teams that Webb will do. And also representative of all science instrument that will be used. But also we're going to see an exoplanet spectrum. So that's a big science team with Webb.

Not only do we want to look at the smallest speck of light in the early universe, we can look at very bright stars in our cosmic garden, to study exoplanet atmosphere. And so we want to understand whether life exists. And the big step toward that is to basically detect exoplanet atmosphere and determine their chemical composition. And you're going to see molecules that are detected — this is the best spectroscopic data ever obtained on a transiting exoplanet, and that was only with one visit.

You're gonna see also beautiful images of star from star-forming region, the Carina Nebula. This is a region where young stars are being formed, you know, several thousands of planetary systems like ours, but you know, several billion years ago. And these images are just so incredible. They look very much like pieces of art that are now revealed by the telescope.

One advice — you're gonna see these pictures on your screen, but they don't really give justice to the quality. Just download them and see the details, zoom them, then you're going to see incredible details. They're not just stunning for the public but also for scientists.

More from Brave Little State: When the Space Race — and arms dealing — came to the Northeast Kingdom

Professor Doyon, any time stories like this come out in the media, lay people like myself often wonder one thing. And that is, is this going to bring us any closer to finding out whether or not we can make some kind of determination, or perhaps best-case scenario (or worst-case scenario), contact with some kind of alien life form that must exist in the universe given how vast it is? Are these images going to get us any closer to answering that question, do you think?

Webb was designed to detect exoplanets. The game plan is to detect biological activity. Worlds that we know are conducive for life to thrive. So the big question, the very first question is, do you look at these planetary systems and answer the question, do they have an atmosphere? And what it's made of? You're going to see molecules that are already familiar today, with this exoplanet spectrum.

So, I mean, it's a bit of a cliché, but I think it's true. Today, we're turning the page on several new chapters to understand the universe, from the early universe, exoplanet atmospheres, how stars and planetary systems form, and many other things.

It's really amazing. And one final question for you, how did it feel to you personally to be selected as one of the experts that NASA would turn to, to analyze these images and data?

Well, I guess it's my position. I'm the principal investigator of the Canadian-built instrument by the Canadian Space Agency. I joined this project 20 years ago, and wow, it's been an incredible journey. And so yeah, that's a very moving moment today, to be here and see these wonderful images and share that with the public.

Have questions, comments, or concerns? Send us a message or tweet your thoughts to @mwertlieb.