Wesleyan University received $1.7 million in early-stage funding from the National Institutes of Health to find an answer to an urgent question: “What’s the first thing that goes wrong, that snowballs into the pathology that we see later in [Alzheimer’s] disease?” said Alison O’Neil, a Wesleyan assistant professor of chemistry, and neuroscience and behavior.

In neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, proteins aggregate in specific locations in the brain, causing the local neurons to die. By the time symptoms manifest in a patient, the damage to the brain is too severe.

“If we’re going to cure Alzheimer’s, we have to stop it before it begins,” said O’Neil. “If we wait until you start losing your memory, it’s kind of too late.”

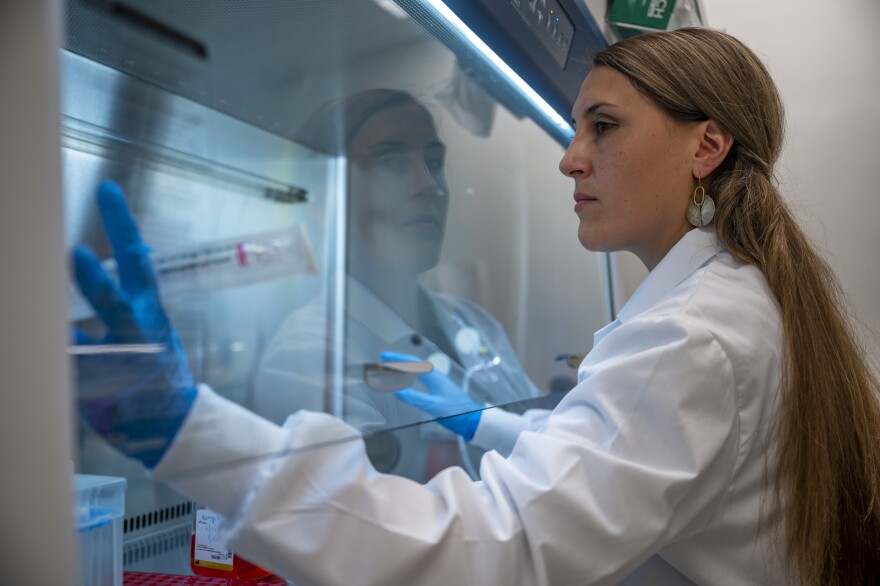

O’Neil will model the disease in her lab by collecting skin cells from Alzheimer’s patients through a biopsy, turning them back into adult induced pluripotent stem cells.

Stem cells are cells that have yet to take on a specific task in the human body. O’Neil will take the adult induced pluripotent stem cells and turn them into the various cell types that make up the brain. By using a special culturing technique, the stem cells will develop into brain organoids, essentially small brains the size of a pea. The organoids are not full brains – for example, there are no blood vessels – but the important areas of the brain that are most affected by Alzheimer’s, and the critical connections between cell types, will develop. Because the stem cells are derived from people with Alzheimer’s, the neurons in the organoids will develop the disease, allowing O’Neil the opportunity to see when the first moments of Alzheimer’s begin.

O’Neil said the biggest problem with Alzheimer's research is that there isn't a good model to study the disease in the lab.

“So what we’ve been looking at is postmortem patient brain samples,” she said. “So this means after the disease has completely ravaged the person’s brain – it’s really late stage. And so what we’re hoping, and this has been shown by others as well, is that these little brain organoids are a pretty good model for neurodevelopmental diseases.”

She said there have been some interesting studies with Zika virus when it first attacks early brain tissue. “And it’s been shown in using Alzheimer’s patient cells, that you can recapitulate some of the big phenotypes we see in patients, which includes amyloid plaques, and these tau neurofibrillary tangles.”

Once the brain develops a huge plaque burden and neurofibrillary tangles, “that’s when you start to lose your memory, and that’s when the disease really takes hold. So we're asking, ‘OK, what happens first?’” O’Neil said.

“I’m amazed and so delighted that this grant was funded, because now the lab is going to start this huge Alzheimer’s project,” she said.