A 1930s musical soundtrack fades down and a group of actors begin taking turns behind a microphone at the Shea Theater in Turners, Falls, Massachusetts, reading complaint letters from almost a hundred years ago.

They were written by customers of Montgomery Ward, a full-service mail-order catalog — the Amazon of its time — and brought to life by Evan Gregg, whose family, he said, never throws anything out.

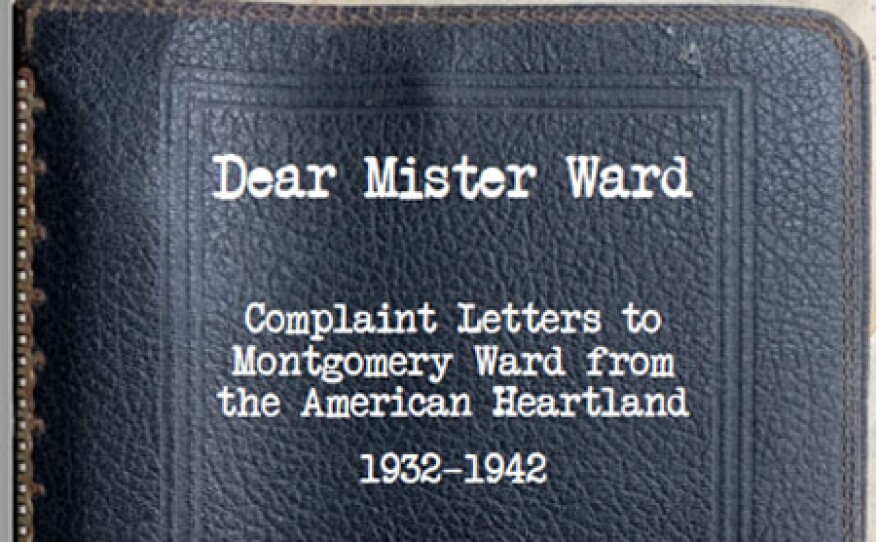

"Dear Mister Ward" — the title of the performance as well as the book of collected missives it's based on — tells the stories of people who lived in a time between two world wars, in mostly rural parts of the country.

They used the Montgomery Ward catalog to buy what they likely couldn't find locally, Gregg said, like sturdy boots, tractors, fashionable clothes, toys and car parts.

Montgomery Ward had a well-known money-back guarantee, and — of course — sometimes things didn't arrive as expected.

Such was the case for M.P. McIntyre, who wrote to Montgomery Ward from Great Falls, Montana.

“Dear sir, I have tried every way I know how to make the horse collar you sent me work on my Model T Ford, but it don't [sic] seem to fit quite right," McIntyre wrote. "Am returning at your expense. And will you kindly send me the carburetor at the same time and price, which is, after all, what I ordered in the first place.”

Another letter from Mrs. Eric Akron, address not included, was about the cow she and her husband owned.

“Dear Company, I imagine this letter will make whoever reads it laugh as the very idea of such a thing made me laugh too,” she wrote. “Mr. Akron has been trying to convince me and the neighbors that a few years ago you used to carry a cow tail in stock for just such cows which he says was made with some kind of a clamp to clamp on to the stub of the cow."

The letters were collected by Gregg's grandmother, Verna Gregg, who worked in the complaint department at Montgomery Ward for 10 years, starting in 1932.

She saved dozens of them, Gregg said. People wrote to say they received the wrong item, or something didn't fit. One letter complained something was broken, even years after it was purchased.

When the younger Gregg found them stashed away among his parents' belongings, he said the tone of the letters struck him.

“They are complaining about certain things, but they're doing so in a very familiar, kind of playful way," Gregg said. "There's no attacking. There's no accusations, really."

He's not sure why his grandmother saved these specific letters.

“I always knew she had a wicked sense of humor and was always interested in the stories of other people," Gregg said. "I'm not sure if she had a historical context in mind or just some cheap laughs at dinner parties.”

A letter signed A.W.W. may have been among the cheap laughs.

"Dear Sirs, may I make a complaint? Here is the scratchy problem," the letter began. "It seems that the paper in your general catalog is getting harder, stiffer, glossier, more polished, and less absorbent in every issue that you put out. Why is this?”

If you only knew, the letter continues, how people use the catalog after its intended usefulness has been achieved. A.W.W. wondered why the catalog couldn’t “serve two useful and pleasant purposes?”

It's evident from a recorded interview with Verna Gregg, before she died in 1990, that she was proud to work at Montgomery Ward.

“I found that when you got a complaint, that Montgomery Ward's would really turn over backward to have a satisfied customer,” Verna Gregg said.

She went on to describe a letter from someone whose engagement had been called off.

“[The letter said] he'd bought an engagement ring and his girl broke up with him and so he had to return the engagement ring," Verna Gregg said on the recording.

“The short of it,” went the actual letter, “is that I have no use for an engagement ring when I am not engaged and do not anticipate any such action for some time. The gal and I can't make a go of it, so I'm looking for other diversions.”

The customer wondered if he could exchange the ring for a radio-phonograph. The price was the same at $39.95.

Not all letters were complaints or casual inquiries, including one Evan Gregg chose not to include in the performance. It came from a woman in Mound City, South Dakota.

“There’s one letter where someone is writing for 'the medicine to get rid of it when you're in the family way,'" Gregg said.

"She says that she can't have a baby right now. You can't tell a lot of context from the letter," he said, and he doesn't know how the company responded.

During the early days of COVD-19, Gregg connected deeply with the letter collection. They were written from far-flung rural locations, places of isolation, Gregg said, and they echoed the situation we were all living through.

“There's this sort of calling out from the wilderness that really stuck with me," Gregg said. "I read them over and over again until I finally decided to share them with people."

Now, using letters that included a town or address, Gregg is attempting to build family trees. If he's successful and can find some descendants, he said there could be a documentary about these 20th century Montgomery Ward customers.

Gregg would interview their family members and film the places where the dispatches were first written. So, it appears, he’s not done with these letters quite yet.